29 Mar 2019

Mount Sibyl and the Lake of Norcia in a seventeenth-century map by Giovanni Antonio Magini

In 1620, Fabio Magini, the son of Giovanni Antonio Magini, the great Italian astronomer and cartographer, published “Italy - A General Description”, the last work completed by his father, who had passed away three years earlier.

The book contained a bounty of detailed maps depicting seventeenth-century Italy, and Giovanni Antonio Magini had not missed the chance to outline the exact position of Mount Sibyl and the Lake of Norcia (also known as the Lake of Pilatus) in two maps: a first one which depicted the Duchy of Spoletium and another one dedicated to the Marches of Ancona.

In the first map, we see Norcia with its multitude of small castles lying in the vicinity: S. Pellegrino, Frascaro, Paganelli, Valcaldara, Notoria, S. Marco, Pescia, Castel S. Maria, Santa Maria della Neve, Ancaiano, Rocca Anolfi, Castelluccio, all featuring almost the same spelling as the names we use today.

In the upper portion of the map, the Sibyl's Cave (“Grotta della Sibilla”) opens its gloomy jaws on a mount raising beside Mount Vettore (“Vittore”). Nearby, the Lake of Norcia (“Lago di Norcia”) is drawn as a single large water surface.

In the second map, the same magical places appear again, with the small hamlet of Castelluccio guarding the plain and the trails leading to the two sites.

In a different work, “Antique and Modern Geography” (“Geographiae, tum veteris tum novae”), a commentary to Ptolemy's classical book on the geography and maps of the antique world, Giovanni Antonio Magini had written the following words:

«Furthermore, in a peak set amid the Apennines, called 'Mount Vettore', lies the Lake of Norcia, whose waters raise with a perennial motion, and then in turn they are seen fall down again, not without the utter astonishment by the onlookers; there evil demons reside, and the illiterate populace believes that they provide answers when summoned. And in the Apennines there is also a huge and frightful cavern which people calls the 'Sibyl's cave', about which many fairy tales are told by liars and shams; according to which many Sorcerers and necromancers were once frequently seen flock to those places, so much so that the inhabitants of Norcia were forced to seal that sibilline cave or hollow, and in addition they put watchful guards by the lake».

[In the original Latin text: «Est in jugo quoque Apennini montis, quod 'Mons Victor' vocatur, Lacus Nursinus, cujus aquae perpetuis motibus salire, vicissimque subsidere cernuntur, non sine magna admiratione, unde ibi Cacodaemones inhabitare, vocatosque responsa dare imperitum vulgus putat. Est etiam in Apennino immane horribileque antrum, quod 'Sybillae caverna' vulgo dicitur, de qua multa fabulosa a mendacibus, ac impostoribus recitantur; quamobrem cum Nursini frequentem olim Magorum, et maleficorum hominum numerum ad haec loca continuo concurrere conspexissent, speculam seu cavernam illam Sybillinam operire coacti fuerunt, ac praeterea custodes ad lacum circumspectos ponere»].

Il Monte Sibilla e il Lago di Norcia in una mappa seicentesca di Giovanni Antonio Magini

Nel 1620, Fabio Magini, figlio di Giovanni Antonio Magini, il grande astronomo e cartografo padovano, pubblicò "L'Italia Descritta in Generale", l'ultima opera completata dal padre, scomparso tre anni prima.

Il volume contiene preziose e dettagliate mappe raffiguranti l'Italia del diciassettesimo secolo, e Giovanni Antonio Magini non si è lasciato certo sfuggire l'occasione per rappresentare l'esatta posizione del Monte Sibilla e del Lago di Norcia (noto anche come Lago di Pilato) all'interno di due mappe differenti: la prima raffigurante il Ducato di Spoleto, la seconda la Marca d'Ancona.

Nella prima mappa, possiamo vedere Norcia accompagnata dalla sua moltitudine di piccoli castelli posti nelle vicinanze: S. Pellegrino, Frascaro, Paganelli, Valcaldara, Notoria, S. Marco, Pescia, Castel S. Maria, Santa Maria della Neve, Ancaiano, Rocca Anolfi, Castelluccio, tutti caratterizzati grosso modo dal medesimo appellativo utilizzato ancora oggi.

Nella parte superiore della mappa, la "Grotta della Sibilla" apre le proprie fauci tenebrose sulla cima di una montagna che si erge accanto al "Monte Vittore". Poco lontano, il "Lago di Norcia" è raffigurato come un singolo, vasto specchio d'acqua.

Nella seconda mappa, gli stessi luoghi dal magico fascino vengono riproposti nuovamente, con il piccolo villaggio di Castelluccio posto a guardia dell'altipiano e dei sentieri che conducono ai due siti.

In una differente opera, "Geografia antica e moderna" (“Geographiae, tum veteris tum novae”), un commento ai classici volumi di Claudio Tolomeo contenenti la geografia e le mappe di tutto il mondo conosciuto nell'antichità, Giovanni Antonio Magini ebbe così a scrivere:

«Inoltre, presso una vetta posta tra i monti Appennini, chiamata 'Monte Vittore', si trova il Lago di Norcia, le cui acque si innalzano in perenne movimento, per poi successivamente essere viste ricadere, non senza grande meraviglia; là risiedono malvagi dèmoni, che il volgo ignorante crede possano rispondere quando evocati. C'è anche, nell'Appennino, un grandissimo e orribile antro, che il popolo chiama 'Caverna della Sibilla', in merito alla quale molte favole vengono narrate da bugiardi e truffatori; per cui un gran numero di maghi e negromanti furono visti recarsi un tempo presso questi luoghi, dimodoché i Nursini furono costretti a chiudere quell'antro o caverna sibillina, e inoltre a porre attenti guardiani presso il lago».

[Nel testo originale latino: «Est in jugo quoque Apennini montis, quod 'Mons Victor' vocatur, Lacus Nursinus, cujus aquae perpetuis motibus salire, vicissimque subsidere cernuntur, non sine magna admiratione, unde ibi Cacodaemones inhabitare, vocatosque responsa dare imperitum vulgus putat. Est etiam in Apennino immane horribileque antrum, quod 'Sybillae caverna' vulgo dicitur, de qua multa fabulosa a mendacibus, ac impostoribus recitantur; quamobrem cum Nursini frequentem olim Magorum, et maleficorum hominum numerum ad haec loca continuo concurrere conspexissent, speculam seu cavernam illam Sybillinam operire coacti fuerunt, ac praeterea custodes ad lacum circumspectos ponere»].

2 Sep 2017

The Apennine Sibyl in a 1643 guidebook for travellers

When David Froelich, a Slovak geographer, mathematician and traveller, published his “Bibliothecae Sive Cynosurae Peregrinantium, hoc est, Viatorii Liber” in 1643, he intended to help the traveller ('peregrinantem', as he writes) in his journey, by providing clear directions as to which land the wayfarer was headed to ('versus quam Mundi plagam illi proficiscendum sit').

Among the descriptions of Gallia, Hispania, Helvetia, Hungaria and many other European and even remote, far-away lands, Italy has a primary position, ancient and illustrious as it was ('inter Europae regiones celeberrima'). And, at the very heart of Italy, the following lines are devoted to Norcia and its renowned Apennine Sibyl:

«NORCIA, which lies by the lake. Here many tales are told about the Sibyl, concealed in her cave. Publius Vergilius Maro calls the town “wintry”, owing to the elevation of the surrounding mountains (which are always capped with snow and engulf the neighbouring land with extreme cold)».

Norcia by a lake, a clear reference to the Lake of Pilatus, once known as the Lake of Norcia. Norcia as the land of the Sibyl. A match that will last for hundreds of years, up to the twentieth century.

[In the original Latin text: «NURSIA, sita ad lacum. Hic multae sunt fabulae de Sibylla, in antro recondita. Virgilius eam frigidam civitatem vocat, propter montium circumjectorum (qui nivibus perpetuo occupantur frigusque ingens propinquis locis conciliant) altitudinem.»]

La Sibilla Appenninica in una guida di viaggio del 1643

Quando David Froelich, geografo, matematico e viaggiatore originario della Slovacchia, pubblicò il suo “Bibliothecae Sive Cynosurae Peregrinantium, hoc est, Viatorii Liber” nel 1643, il suo intento era quello di assistere il viaggiatore ('peregrinantem', come egli stesso scrive) nel corso del suo cammino, rendendo disponibili indicazioni chiare a proposito delle terre verso le quali il viandante era diretto ('versus quam Mundi plagam illi proficiscendum sit').

Tra le descrizioni relative a Gallia, Hispania, Helvetia, Hungaria e a tante altre terre d'Europa, nonché ad ulteriori regioni ancor più remote ed esotiche, l'Italia ha una posizione preminente, a motivo della sua antica ed illustre storia ('inter Europae regiones celeberrima'). E, proprio al cuore dell'Italia, Froelich dedica le seguenti parole a Norcia e alla sua famosa Sibilla Appenninica:

«NORCIA, situata in prossimità del lago. Qui si narrano molte favole a proposito della Sibilla, nascosta nel suo antro. Virgilio definisce la città come 'gelida', a causa dell'elevazione delle circostanti montagne (che sempre sono ricoperte di neve perenne e inondano i luoghi vicini di freddo notevolissimo)».

Norcia in prossimità di un lago, un chiaro riferimento al Lago di Pilato, un tempo conosciuto proprio come il Lago di Norcia. Norcia come terra della Sibilla. Un accostamento che sarebbe durato per centinaia di anni, fino al ventesimo secolo.

[Nel testo originale latino: «NURSIA, sita ad lacum. Hic multae sunt fabulae de Sibylla, in antro recondita. Virgilius eam frigidam civitatem vocat, propter montium circumjectorum (qui nivibus perpetuo occupantur frigusque ingens propinquis locis conciliant) altitudinem.»]

17 Jul 2017

A vivid description of Mount Sibyl: impressions by Fernand Desonay

Belgian philologist Fernand Desonay was so enamoured of the Apennine Sibyl's legend that he travelled many times to Mount Sibyl. We should learn from the passionate words he wrote about his journeys, they fully show the immense attractiveness of the ancient tale centered on this famous peak:

«On August, 26th 1929 I was able to consider, from the back of a small brown donkey, the mists swirling on the mountain-sides of the Apennines... The vision of those mountains seizes your heart; the silence around, it utterly petrifies your soul. You see Mount Vettore at last, with the lake of Pilatus! Up there, the ancestral worship and tales have their roots!... We are setting off in search of a mystery. [...] I have in my pocket the work by Antoine de La Sale; for I intend to check all the geographical information provided in the Chantilly manuscript. After much effort, we have reached the base of the “crown”. La Sale says that it's a cliff some fifteen feet high, “cut in the mount along the whole circumference”. It's right. When seen from a distance, this crown may truly appear as a fortress, or a temple. Sure enough, the vista is so picturesque; and it can hardly be reckoned it is just a natural feature: such a large bulk of rock crushing the mountain-top and shaped as a dome must have striken the mind's eye.»

[in the original French wording: «Le 26 août 1929, je pouvais contempler, du haut de l'échine d'un petit âne brun, les jeux de la 'nebbia' sur le pentes de l'Apennin... [...] L'aspect de ces montagnes vous serre le coeur; le silence d'alentour, on dirait qu'il vous paralyse. Voilà donc le Vettore, avec le lac de Pilate! C'est là-haut qu'ont surgi les cultes antiques et les légendes!... Nous partirons à la découverte du mystère. [...] J'ai dans ma poche le texte d'Antoine de La Sale; car je veux contrôler toutes les indications topographiques du manuscrit de Chantilly. Après de longs efforts, nous sommes arrivés au pied de la “couronne”. La Sale dit qu'il s'agit d'une roche haute de cinq mètres environ, “taillée dans la montagne sur tout le pourtour”. C'est exact. Vue de loin, cette couronne peut donner l'impression d'une forteresse, voire d'un temple. Certes, tout ceci est fort caractéristique; et l'on ne peut croire qu'il s'agisse d'une formation naturelle: pareille masse qui écrase la montagne en forme de coupole a dû frapper l'imagination.»]

Una vivida descrizione del Monte Sibilla: immagini di Fernand Desonay

Il filologo belga Fernand Desonay era così affascinato dalla leggenda della Sibilla Appenninica da recarsi più volte sul Monte Sibilla. Dovremmo lasciarci guidare dalle appassionate parole da lui scritte a proposito delle sue visite, perché ci mostrano quanto intensamente possa operare la magia dell'antico racconto incentrato su questa famosissima montagna:

«Il 26 agosto 1929 ho potuto contemplare, dall'alto del dorso di un piccolo asino bruno, i giochi della nebbia sui versanti dell'Appennino... [...] L'aspetto di queste montagne vi stringe il cuore; il silenzio tutt'attorno, si direbbe che vi paralizzi. Eccolo dunque il Vettore, con il lago di Pilato! È proprio lassù che sono sorti i culti antichi e le leggende!... Stiamo per partire alla scoperta del mistero. [...] Porto con me nella tasca il testo di Antoine de La Sale; perché intendo controllare tutte le indicazioni topografiche contenute nel manoscritto di Chantilly. Dopo molti sforzi, siamo infine arrivati ai piedi della “corona”. La Sale dice che si tratta di una parete di roccia alta circa cinque metri, “tagliata nella montagna lungo tutta la circonferenza”. È esatto. Vista da lontano, questa corona può dare l'impressione di una fortezza, o di un tempio. Di certo, tutto questo è molto pittoresco; e quasi non si può credere che possa trattarsi di una formazione naturale; una tale massa che schiaccia la montagna in forma di cupola deve avere colpito molto l'immaginazione.»

[nel testo originale francese: «Le 26 août 1929, je pouvais contempler, du haut de l'échine d'un petit âne brun, les jeux de la 'nebbia' sur le pentes de l'Apennin... [...] L'aspect de ces montagnes vous serre le coeur; le silence d'alentour, on dirait qu'il vous paralyse. Voilà donc le Vettore, avec le lac de Pilate! C'est là-haut qu'ont surgi les cultes antiques et les légendes!... Nous partirons à la découverte du mystère. [...] J'ai dans ma poche le texte d'Antoine de La Sale; car je veux contrôler toutes les indications topographiques du manuscrit de Chantilly. Après de longs efforts, nous sommes arrivés au pied de la “couronne”. La Sale dit qu'il s'agit d'une roche haute de cinq mètres environ, “taillée dans la montagne sur tout le pourtour”. C'est exact. Vue de loin, cette couronne peut donner l'impression d'une forteresse, voire d'un temple. Certes, tout ceci est fort caractéristique; et l'on ne peut croire qu'il s'agisse d'une formation naturelle: pareille masse qui écrase la montagne en forme de coupole a dû frapper l'imagination.»]

13 Jul 2017

The most beatiful words ever written about Mount Sibyl: Fernand Desonay

There is a man, in modern times, who had a special dream about Mount Sibyl. He was a philologist, a man who used to live his days among old Italian legends and the tale of Tannhäuser. Fernand Desonay, from Belgium, had journeyed many times up to the peak of Mount Sibyl to take part into the excavations campaigns carried out by his Italian friends.

He left precious, perfectly beautiful words on his dream, which I use to quote in my presentation sessions on the Sibyl's legend. I have recently found the original French wording, which is contained in his article “Les sources italiennes de la legende de Tannhäuser”. Now I want to share them with all the lovers of this ancient legend:

«Je songe à la Sibylle. Mon regard va, va... Il escalade les rampes des montagnes, franchit les précipices... Sous la couronne de rochers, voici la déesse, - c'est elle! - inspiratrice nostalgique du plus beau des songes humains...»

«I am dreaming of the Sibyl... My eyes travel up and further up... My gaze climbs the crests, jumps across the ravines... Beneath the crown of stone, there I see the goddess - there she is! - she, who inspires my longing for the most ravishing among human dreams...».

Le più belle parole mai scritte sul Monte Sibilla: Fernand Desonay

C'è un uomo che, in tempi moderni, ha nutrito un sogno speciale a proposito del Monte Sibilla. Si trattava di un filologo, un uomo che aveva vissuto a lungo in compagnia delle antiche leggende italiane e del mito di Tannhäuser. Fernand Desonay, di origine belga, aveva viaggiato molte volte fino alla cima del Monte Sibilla, partecipando alle campagne di scavo effettuate dai suoi amici italiani.

Desonay ci ha lasciato parole preziose e di perfetta bellezza a proposito del suo sogno, parole che sono solito citare nel corso delle mie presentazioni sulla leggenda della Sibilla. Recentemente, mi è capitato di trovare finalmente le sue parole nel testo francese originale, contenute nell'articolo "Le fonti italiane della leggenda di Tannhäuser". Voglio ora condividerle con tutti gli appassionati di questa antica leggenda:

«Je songe à la Sibylle. Mon regard va, va... Il escalade les rampes des montagnes, franchit les précipices... Sous la couronne de rochers, voici la déesse, - c'est elle! - inspiratrice nostalgique du plus beau des songes humains...»

«Io sogno la Sibilla. Il mio sguardo va, sale ancora... Si inerpica lungo le coste dei monti, scavalca i dirupi... E, sotto la corona di roccia, ecco infine la divinità - è lei! - l'ispiratrice perduta del più bello dei sogni degli uomini...»

27 Jun 2017

Vincenzo Luchino: the earliest map of the Marche province (with Mount Sibyl)

The antecedent to all sixteenth-century maps published in the Flanders (Ortelius, De Jode) and showing the position of Mount Sibyl is the rare map issued in 1564 by Vincenzo Luchino, a bookseller who had set up his shop in Rome and edited a number of maps for the local market (in the so-called “Lafrerian Style”: Antoine Lafréry was the first engraver who used to publish single maps for specifically interested clients).

According to scholars, Luchino's map was well known to Oertelius who elaborated on it and published his own map of the “Marcha Anconae olim Picenum” in the 1573 edition of the “Theatrum Orbis terrarum”, based on the work by Luchino.

In the map, the “M. de la Sibilla” is clearly visible, in the vicinity of “Arquato”, “M.S. Maria in Galio”, “M. Monico” and the hamlet of “Cainuraza” (not easily identified in modern maps; the place is also present in Ortelius' cartography).

You can download a higher-resolution version of Luchino's map from here.

Vincenzo Luchino: la più antica mappa delle Marche (con Sibilla)

L'antesignana di tutte le mappe cinquecentesche pubblicate nelle Fiandre (Ortelius, De Jode), nelle quali è marcata la posizione del Monte Sibilla, è la rara cartografia predisposta da Vincenzo Luchino, un libraio romano che pubblicò varie mappe per il mercato locale (secondo lo stile delle cosiddette "Raccolte Lefreriane": Antoine Lafréry fu il primo incisore a pubblicare mappe sciolte sulla base degli interessi di specifici clienti).

Secondo gli studiosi, la mappa era ben nota a Ortelius, il quale in seguito pubblicò la propria mappa della "Marcha Anconae olim Picenum" nell'edizione del 1573 del “Theatrum Orbis Terrarum”, basandosi proprio sull'opera di Luchino.

Nella mappa, il "M. de la Sibilla" è chiaramente indicato, nelle vicinanze di "Arquato", "M.S. Maria in Galio", "M. Monico" e del villaggio di "Cainuraza" (di non facile identificazione nelle mappe moderne; il toponimo è presente anche nella cartografia di Ortelius).

È possibile visualizzare una versione a più elevata risoluzione della mappa di Luchino qui.

23 Jun 2017

Who told the great geographer Ortelius of the Apennine Sibyl? A new line of investigation

In 1570, Abraham Ortelius published his “Theatrum Orbis Terrarum”, a collection of maps that is considered to be the forerunner of all world atlases. Ortelius dedicated much space to Mount Sibyl and its legendary tale. But who provided the illustrious Flemish geographer with so detailed a description of a legend pertaining to a remote Italian region?

Acting as contemporary detectives, let's try to probe into facts so as to provide an answer to this thrilling question.

First, let's consider Ortelius' map, showing the exact position of Mount Sibyl.

Ortelius did not create his maps all by himself, he had local contributors established in all European countries. In particular, according to researchers, the “Marcha Anconae olim Picenum” map designed by Ortelius was taken by an earlier map made by Vincenzo Luchino, a map publisher based in Rome (a letter dated 1572 esists in which a Roman librarian, Giovanni Orlandi, recommended Luchino's map to the attention of Ortelius). “The Apennine Sibyl - A Mystery and a Legend” will soon release this map in a high resolution version.

And now, the caption to Ortelius' map, which narrates the Sibyl's tale in detail.

As reported by Giorgio Mangani (a well-informed contemporary researcher), the info included by Ortelius in his maps was «mostly provided by extemporary local correspondents, enlisted from a milieu of men of letters, aristocrats and sometimes even people from military ranks, not always able to collect the geographical elements they were asked for with a reliable methodology; they were rarely men of science, more frequently they used to be engaged in different areas of studies».

A list of Ortelius' correspondents is presented in the initial sections of the “Theatrum”, including a biography of Ortelius written by Francis Sweert, an intimate of the illustrious scientist. Sweert says that Ortelius had many friends of great promincence and learning, «amicos coluit magni et nominis et eruditionis viros». The biographer continues by mentioning the names of the fellow-scholars residing in various European countries of that time. As for Italy, the list includes «Fulvium Ursinum, Franciscum Superantium & Ioannes Sambucum» (see figure).

Domenico Francesco Superantio was a geographer who lived and worked in Italy's Veneto province. Ioannes Sambucus - whose real name was János Zsámboky - was a Slovak historian who lived and studied in Italy. Actually it seems they have nothing to do with the Apennine Sibyl and its legend.

So the possible source for Ortelius' information on the Apennine Sibyl was perhaps Flavio Orsini. There are actually two of them, bearing the same name and active in the second half of the sixteenth century: the first was a most illustrious historian, archeologist, and one of the greatest collectors of antiquities of his time; the second was the bishop of Spoletium (and also of Norcia) from 1563 to 1581.

Both of them could have written the famous caption on the Apennine Sibyl published by Ortelius: for sure they both knew everything about the legend. Further research will be needed to ascertain who told Ortelius of Mount Sibyl, irrevocably consigning this thrilling fairy tale to the wider European lore.

Chi fu a raccontare al grande geografo Ortelius la leggenda della Sibilla? Una nuova linea di ricerca

Nel 1570, Abraham Ortelius pubblicò il suo "Theatrum Orbis Terrarum", un compendio di carte geografiche che costituisce l'antesignano di tutti i moderni atlanti. Ortelius dedicò un notevolissimo spazio al Monte Sibilla e alla sua leggenda. Ma chi fu a fornire all'illustre geografo fiammingo tutte quelle dettagliate informazioni relative ad una leggenda italiana così remota?

Come moderni investigatori, proveremo ad analizzare i fatti a noi noti per tentare di reperire una risposta a questa interessante domanda.

In primo luogo, consideriamo la mappa di Ortelius, la quale mostra con precisione la posizione del Monte Sibilla.

Ortelius non creava le proprie mappe in solitudine, egli si avvaleva di contributori locali che risiedevano in vari Paesi d'Europa. In particolare, secondo i moderni ricercatori, la mappa disegnata da Ortelius e denominata “Marcha Anconae olim Picenum” fu tratta da una precedente cartografia realizzata da Vincenzo Luchino, un editore di mappe operante in Roma (esiste una lettera datata 1572 nella quale un libraio romano, Giovanni Orlandi, raccomanda all'attenzione di Ortelius proprio la mappa di Luchino). "The Apennine Sibyl - A Mystery and a Legend" pubblicherà presto anche questa mappa in versione ad alta risoluzione.

In secondo luogo, consideriamo la didascalia che Ortelius ha affiancato alla mappa, contenente il racconto dettagliato della leggenda della Sibilla.

Come rilevato da Giorgio Mangani (un ricercatore contemporaneo di grande esperienza), i dati inclusi da Ortelius nelle proprie mappe erano «prevalentemente fornite da corrispondenze locali un po’ improvvisate, reclutate in un ambiente di letterati, aristocratici e a volte militari, piuttosto raramente capaci di raccogliere gli elementi geografici loro richiesti con una certa sistematicità; solo raramente di scienziati, ma comunque impegnati in ricerche diverse da quelle territoriali».

Una lista dei corrispondenti di Ortelius è presentata nelle sezioni iniziali del "Theatrum", all'interno della biografia di Ortelius redatta da Francis Sweert, stretto collaboratore dell'illustre scienziato. Sweert ci racconta di come Ortelius intrattenesse relazioni con personaggi di grande fama ed erudizione, «amicos coluit magni et nominis et eruditionis viros». Il biografo continua elencando i nomi dei colleghi eruditi residenti nelle varie regioni d'Europa dell'epoca. Per quanto riguarda l'Italia, la lista comprende «Fulvium Ursinum, Franciscum Superantium & Ioannes Sambucum» (vedere figura).

Domenico Francesco Superantio era un cartografo originario del Veneto. Ioannes Sambucus - il cui vero nome era János Zsámboky - era uno storico della Slovacchia che aveva vissuto e lavorato in Italia. Nessuno dei due sembrerebbe avere nulla a che fare con la Sibilla Appenninica e la sua leggenda.

Così, la possibile fonte delle informazioni pervenute ad Ortelius in merito alla Sibilla potrebbe essere costituita da Flavio Orsini. In effetti, sono noti due Orsini con questo nome, attivi nella seconda metà del sedicesimo secolo: il primo fu un noto storico e archeologo, nonché uno dei più grandi collezionisti di antichità del suo tempo; il secondo fu vescovo di Spoleto (e dunque anche di Norcia) dal 1563 al 1581.

Ognuno dei due avrebbe potuto suggerire la famosa didascalia sulla Sibilla Appenninica per Ortelius: sicuramente, entrambi conoscevano tutto di quella leggenda. Nuove e più approfondite ricerche saranno necessarie per accertare chi raccontò all'Ortelius del Monte Sibilla, consegnando irrevocabilmente questa emozionante leggenda al più ampio scenario delle grandi tradizioni europee.

18 Jun 2017

Abraham Ortelius, the great geographer bewitched by Mount Sibyl

When Abraham Ortelius published his “Theatrum Orbis Terrarum” in 1570, he set a milestone in scientific geography, with the issue of the first modern atlas ever.

Mount Sibyl was there, its position being clearly marked in the map of the “Marcha Anconae” once known as “Picenum”, as we presented in a previous post.

And that was not all. To highlight the utter importance of the mysterious Italian mountain, Ortelius included a detailed caption, showing how his mind had been seized and striken by our amazing legend. The following is the English translation of his text (also see figure):

«In this place, looming over the mentioned territory, where the Apennine Mountain Range exceeds itself with the most elevated peaks, that ghastly Cavern is found whose name is Sibyl's (people calls it the “Sibyl's Cave”) and the Elysium is supposed to be there. The populace also likes to believe that in this Cave of the Sibyl a large kingdom exists, full of magnificent, kingly palaces and enchanting gardens, and sensual maidens and every kind of delightful pleasures in great abundance. And all these things would be available to those who dare to get into that cavern (whose entranceway is visible to all). According to what is reported, after a full year of stay the visitors are free to leave the cave (if they wish so) and are so blessed by the Sibyl that when they come back to the outside world they live the remaining time of their life in utter blissfulness.»

[in the original Latin text: «Apenninus mons hoc loco, ubi huic regioni imminent, editissimis iugis se ipsam superat, in quibus Antrum illud horribile est quod Sibyllae cognominant (Grotta de la Sibylla vulgo) atque Campos Elysios fingunt. Vulgus enim in hoc Antro Sibyllam quandam somniat, quae hic regnum amplum magnificis Regiisque palatiis plenum, hortis amoenissimis confitum, lascivientibusque puellis, et omnis generis deliciarum copia abundantem possideat. Atque haec omnia comunicari cum iis qui eam per hoc antru (quod omnibus pateat) adeunt. Postquam vero per annum in eo permanserint, liberam egrediendi facultatem (si velint) eis a Sibylla largiri praedicat, atque ex eo ad nos reversis, felicissimo deinceps toto vitae tempore uti asserit.»]

How could the Flemish geographer Ortelius know about the Sibyl? Who told him of Mount Sibyl and its incredibly fascinating legend, so that he could include such a detailed description in his “Theatrum Orbis Terrarum”?

“The Apennine Sibyl - A Mystery and a Legend” is proud to provide another significant contribution to the research on the Sibyl's legend by publishing - for the first time ever - the name of the person who knew both the Sibyl's legend and Ortelius: the man who explained to the northern-European cartographer the secrets of the Apennine Sibyl.

[to be continued]

Abraham Ortelius, il grande geografo stregato dal Monte Sibilla

Quando Abraham Ortelius diede alle stampe il suo "Theatrum Orbis Terrarum" nel 1570, egli segnò una pietra miliare nel campo delle scienze geografiche, con la pubblicazione del primo moderno atlante della storia.

Il Monte Sibilla era lì, la sua posizione marcata con precisione all'interno della mappa della “Marcha Anconae” un tempo nota come “Picenum”, come abbiamo già avuto occasione di illustrare in un precedente post.

E questo non era tutto. Per rendere ancor più evidente la grandissima importanza della misteriosa montagna italiana, Ortelius inserì anche una dettagliata didascalia, la quale testimonia di come la sua fantasia fosse stata colpita e catturata dalla nostra affascinante leggenda. Quella che segue è la traduzione italiana delle sue parole (vedere anche la figura):

«In questo luogo, che incombe sui territori nominati, e dove la Catena degli Appennini supera se stessa con i picchi più elevati, si trova quell'Antro orribile intitolato alla Sibilla (chiamata dal volgo "Grotta della Sibilla"), dove si crede che si trovino i Campi Elisi. Al popolino infatti piace credere che in questa Grotta della Sibilla esista un grande regno, pieno di magnifici palazzi regali e incantevoli giardini, e sensuali fanciulle e ogni genere di delizie in grandissima copia. E tutte queste cose sarebbero alla portata di coloro che osassero penetrare in quella caverna (il cui ingresso è a tutti visibile). Secondo quanto si racconta, dopo un intero anno di permanenza i visitatori sono liberi di uscire dalla grotta (se così desiderano) e sono così munificati dalla Sibilla che, quando essi ritornano nel nostro mondo, trascorrono il resto della loro vita nella felicità più perfetta.»

[nel testo originale latino: «Apenninus mons hoc loco, ubi huic regioni imminent, editissimis iugis se ipsam superat, in quibus Antrum illud horribile est quod Sibyllae cognominant (Grotta de la Sibylla vulgo) atque Campos Elysios fingunt. Vulgus enim in hoc Antro Sibyllam quandam somniat, quae hic regnum amplum magnificis Regiisque palatiis plenum, hortis amoenissimis confitum, lascivientibusque puellis, et omnis generis deliciarum copia abundantem possideat. Atque haec omnia comunicari cum iis qui eam per hoc antru (quod omnibus pateat) adeunt. Postquam vero per annum in eo permanserint, liberam egrediendi facultatem (si velint) eis a Sibylla largiri praedicat, atque ex eo ad nos reversis, felicissimo deinceps toto vitae tempore uti asserit.»]

Ma come fu possibile per il geografo fiammingo Ortelius venire a conoscenza della Sibilla? Chi fu a raccontargli del Monte Sibilla e della sua incredibile leggenda, tanto da permettergli di inserire, nel suo “Theatrum Orbis Terrarum”, una descrizione così dettagliata?

“The Apennine Sibyl - A Mystery and a Legend” è orgoglioso di fornire un ulteriore significativo contributo alla ricerca sulla leggenda della Sibilla, pubblicando oggi - per la prima volta - il nome del personaggio che ben conosceva sia la leggenda sibillina che lo stesso Ortelius: l'uomo che illustrò al cartografo nordeuropeo i segreti della Sibilla Appennica.

[continua]

16 Jun 2017

From the Apennine to Flanders to the UK: the amazing journey of the Sibyl

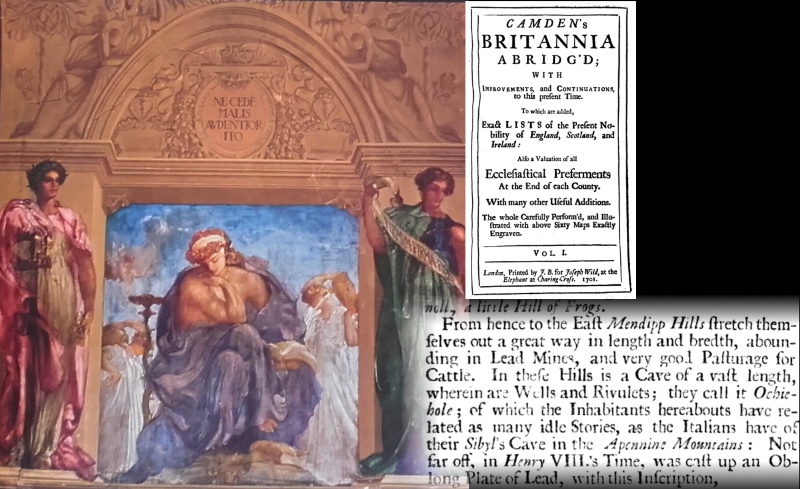

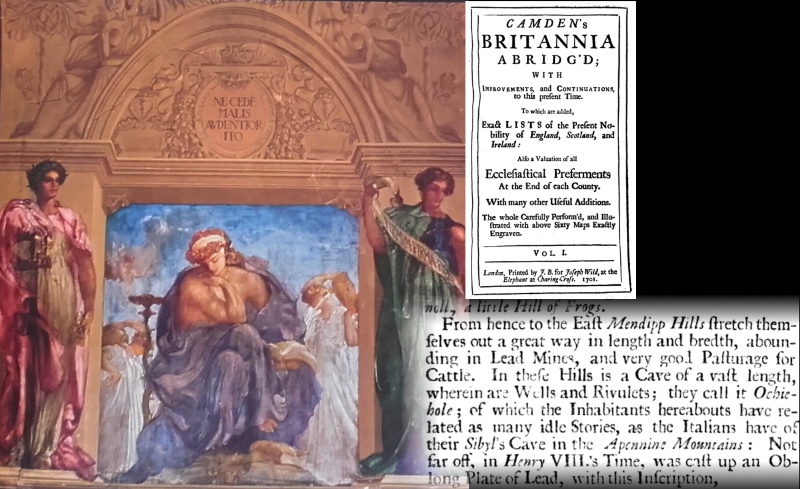

In a previous post, we found that in 1586 the fame of the Apennine Sibyl had reached the British Islands, as attested in a quote from William Camden, the great sixteenth-century historian. But how Camden had come to know about the existence of an Apennine Sibyl in far-away Italy?

The answer - never published by anybody before - is clear to us: the legend travelled through Flanders.

Why? Because it is definitely known to scholars that William Camden wrote his work "Britannia" under the influence of Abraham Ortelius from Antwerp, the famous Flemish cartographer, and the author of the greatest geographical work of his age, the "Theatrum Orbis Terrarum".

Ortelius had a number of correspondents in various countries to help him in the design of country maps: as to the British Islands, he had established very close links precisely with William Camden. Letters used to come and go between the two on such learned matters as the antique names of Roman Britain and other scholarly topics.

No doubt it was Ortelius who first told Camden about the Apennine Sibyl: Ortelius, the man who purposedly marked the position of Mount Sibyl in his world-famous "Theatrum Orbis Terrarum", within the map of "Marcha Anconae olim Picenum" (see figure), and was so utterly fascinated by the story of the Apennine Sibyl as to accompany the map with a very long caption. Half of which was fully dedicated to the wondrous legend of the Sibyl of the Apennines.

Dall'Appennino alle Fiandre fino al Regno Unito: il fantastico viaggio della Sibilla

In un precedente post, abbiamo trovato come nel 1586 la fama della Sibilla Appenninica avesse raggiunto anche le Isole Britanniche, come testimoniato da una citazione tratta da William Camden, il grande storico inglese del sedicesimo secolo. Ma come è potuto accadere che Camden sia potuto venire a conoscenza dell'esistenza di una Sibilla Appenninica nella lontana Italia?

La risposta - mai pubblicata in precedenza da nessuno - è chiarissima ai nostri occhi: la leggenda ha viaggiato attraverso le Fiandre.

Perché? Perché è ben noto tra gli studiosi il fatto incontestabile che William Camden abbia scritto la propria opera "Britannia" sotto la profonda influenza di Abraham Ortelius di Anversa, il famoso cartografo fiammingo, nonché autore della più grande opera cartografica del proprio secolo, il "Theatrum Orbis Terrarum".

Ortelius disponeva di vari corrispondenti situati in diversi Paesi, i quali collaboravano con lui nella realizzazione delle differenti mappe geografiche nazionali: per quanto riguardava le Isole Britanniche, egli aveva stabilito una relazione molto stretta proprio con William Camden. Esisteva infatti tra i due studiosi un fitto scambio epistolare, nel quale venivano affrontati temi dottissimi quali gli antichi toponimi della Britannia Romana e altri argomenti di elevata erudizione.

Non ci può essere alcun dubbio: fu proprio Ortelius a narrare a Camden della Sibilla Appenninica. Ortelius, l'uomo che aveva deliberatamente marcato la posizione del Monte Sibilla nel suo illustre "Theatrum Orbis Terrarum", all'interno della mappa della "Marcha Anconae olim Picenum" (vedi figura), e che era così totalmente affascinato dal racconto della Sibilla Appenninica da corredare la mappa con una lunghissima didascalìa. Metà della quale era interamente dedicata alla fantastica leggenda della Sibilla degli Appennini.

11 Jun 2017

“The Apennine Sibyl - A Mystery and a Legend” discovers a previously unknown quote of the Sibyl's legend from Great Britain

Not many people know that the fame of the Apennine Sibyl has travelled, in past centuries, as far as the British Islands. Actually no scholar has ever highlighted this fact. “The Apennine Sibyl - A Mystery and a Legend” is proud to present today this unprecedented mark left by our unique Italian legend in a northern-European country: the Great Britain.

In 1586, the great British historian William Camden published his masterwork “Britannia”, a fundamental geographical description of the British Islands. In describing one of the few caverns existing in his homeland, near the town of Wells (the “Ochie-Hole”, known in our present days as the “Wookey Hole Caves”), he wrote the following words:

«In these Hills is a Cave of a vast length, wherein are Wells and Rivulets; they call it 'Ochie-hole'; of which the Inhabitants hereabouts have related as many idle Stories, as the Italians have of their Sibyl's Cave in the Apennine Mountains».

This is a major testimony to the far-reaching might of the Italian Sibyl's legend, and a brand new clue to the enthralling puzzle game we are playing to retrace the origin and development of the Apennine Sibyl's mithycal story.

"Sibilla Appenninica - Il Mistero e la Leggenda" scopre una citazione in precedenza ignota proveniente dalla Gran Bretagna e relativa alla leggenda della Sibilla

Non molti studiosi sono al corrente del fatto che la fama della Sibilla Appenninica ha raggiunto, negli scorsi secoli, anche le lontane Isole Britanniche. "Sibilla Appenninica - Il Mistero e la Leggenda" è orgogliosa oggi di presentare questa traccia, in precedenza sconosciuta, lasciata dalla nostra peculiare leggenda italiana in una landa nordeuropea: la Gran Bretagna.

Nel 1586, il grande storico inglese William Camden pubblicò la propria opera fondamentale "Britannia", una monumentale descrizione degli aspetti geografici delle Isole Britanniche. Nel descrivere una delle poche caverne esistenti nel proprio Paese d'origine, una cavità posta vicino alla città di Wells ("Ochie-Hole", oggi conosciuta come le "Wookey Hole Caves"), egli scrisse le seguenti parole:

«Tra queste Colline si trova una Grotta di estesa lunghezza, nella quale vi sono Pozzi e Acque scorrenti; essa è chiamata 'Ochie-hole'; a proposito della quale gli Abitanti delle zone limitrofe hanno raccontato molte storie fantasiose, tante quante gli Italiani ne hanno raccontate della loro Grotta della Sibilla posta tra le Montagne dell'Appennino».

[nel testo originale inglese: «In these Hills is a Cave of a vast length, wherein are Wells and Rivulets; they call it 'Ochie-hole'; of which the Inhabitants hereabouts have related as many idle Stories, as the Italians have of their Sibyl's Cave in the Apennine Mountains»]

Si tratta di un'importantissima testimonianza della potente capacità di espansione della leggenda italiana della Sibilla: un nuovo straordinario elemento appartenente a quel rompicapo affascinante che stiamo a mano a mano costruendo per scoprire l'origine e lo sviluppo della storia meravigliosa della Sibilla Appenninica.

5 Jun 2017

Apennine Sibyl: the summoning of the clouds

Anyone who had ever made an attempt at reaching the Sibyl's mountain-top knows well that the legendary prophetess has many ways to prevent undesired visitors from getting to her cliff: suddenly, rolling clouds extend through the sky carried by a cold, damp wind, and heavy lashes of rain start hitting the wayfarer's face: this is the signal that we must go back, and quickly, for the Apennine Sibyl bids no welcome.

Giovanni Battista Lalli, a poet from Norcia who lived in the seventeenth century, had a first-hand experience of this same occurrence, as he himself wrote in his poem “Ruined Jerusalem”:

«And if anyone unwelcomed dares to draw too near, and she chooses to deny herself to him, in various manners he repels him from his venturesome design. Sometimes she fills the sky with gloomy clouds carrying the rain, so that a horrible storm comes to life; sometimes with a mortal threat, any mercy dispelled, she unleashes the savage beasts against the wayfarer.»

[in the original Italian text:

E se quivi appressarsi alcun s'accinge,

Ch'à lei no piaccia, e d'introdur no'l degna;

Con diverse maniere il risospinge

Da quell'impresa, che tentar disegna.

D'atre, e gravide nubi hor l'aria cinge,

Che ria tempesta à partorir ne vegna;

Hor minacciosa, ogni pietà sbandita,

Contro di quel l'horrende belve irrita.]

Sibilla Appenninica: la chiamata delle nubi

Chiunque abbia mai tentato di raggiungere la vetta del Monte Sibilla sa bene come la leggendaria profetessa disponga di molti mezzi per impedire ai visitatori indesiderati di porre il piede sulla sua rupe: all'improvviso, nubi vorticanti cominciano a riempire il cielo, trasportate da un vento freddo e umido, mentre pesanti frustate di pioggia iniziano a colpire il viso del viandante: è il segnale che occorre tornare indietro, e in fretta, perché la Sibilla Appenninica non ha alcuna intenzione di darci il benvenuto.

Giovanni Battista Lalli, un poeta nursino vissuto nel secolo diciassettesimo, ha potuto esperimentare di persona questo fenomeno, come egli stesso ci racconta nel suo poema "Gerusalemme desolata":

«E se quivi appressarsi alcun s'accinge,

Ch'à lei no piaccia, e d'introdur no'l degna;

Con diverse maniere il risospinge

Da quell'impresa, che tentar disegna.

D'atre, e gravide nubi hor l'aria cinge,

Che ria tempesta à partorir ne vegna;

Hor minacciosa, ogni pietà sbandita,

Contro di quel l'horrende belve irrita.»

28 Mar 2017

The Apennine Sibyl in a sixteenth-century vatican manuscript: the full picture (1500 x 2000 pixels)

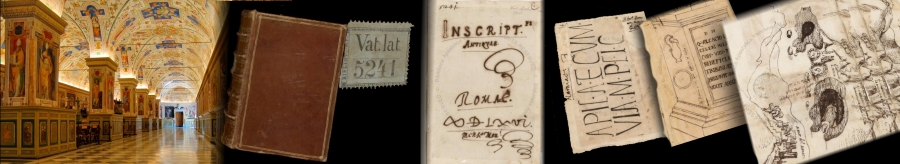

The time has come to publish the full, hi-resolution image of the map included in the Vatican manuscript “Vat Lat 5241”: an astounding sixteenth-century diagram connected to the Sibyl's legendary tale.

For the first time ever, you can now download the high-quality version of the map from my website The Apennine Sibyl - A mistery and a legend (The Vatican Map), the only site providing original, first-hand information on the Apennine Sibyl's legend and lore nobody else can retrieve, analyse, process and present the way we do.

Who drew the map? And why? And how did it happen that a map so peculiarly linked to an eerie lore was included in a scholarly collection of Latin inscriptions?

Stay tuned, because in the next post I will submit to the general public and research community a brand-new, unprecedented clue about the legend of the Apennine Sibyl and its potential connection to another sinister enigma of the past, that was once well known to all men of letters: the arcane secret of the Stone of Bologna.

La Sibilla Appenninica in un manoscritto vaticano del sedicesimo secolo: l'immagine completa (1500 x 2000 pixel)

È giunto il momento di rendere pubblica l'immagine completa e ad alta risoluzione ritrovata all'interno del manoscritto vaticano “Vat Lat 5241”: un incredibile diagramma, risalente al sedicesimo secolo, collegato al leggendario racconto della Sibilla Appenninica.

Per la prima volta in assoluto, potete oggi scaricare una versione di qualità elevata della mappa dal mio sito web Sibilla Appenninica - Il mistero e la leggenda (la Mappa Vaticana), l'unico sito in grado di fornire informazioni originali e di prima mano sulla leggenda della Sibilla Appenninica: informazioni che nessun altro può reperire, analizzare, elaborare e presentare nel modo in cui i dati sono presentati al pubblico nel nostro spazio web.

Chi ha disegnato la mappa? E perché? E come è possibile che un diagramma collegato in modo così peculiare ad una sinistra leggenda si trovi ad essere incluso in un'erudita raccolta di antiche iscrizione latine?

Rimanete collegati, perché nel prossimo post sottoporrò all'attenzione del pubblico e dei ricercatori del settore un nuovo indizio inedito concernente la leggenda della Sibilla Appenninica ed il suo possibile legame con un altro sinistro enigma del passato, un tempo ben noto a tutti gli eruditi: l'arcano mistero della Pietra di Bologna.

27 Mar 2017

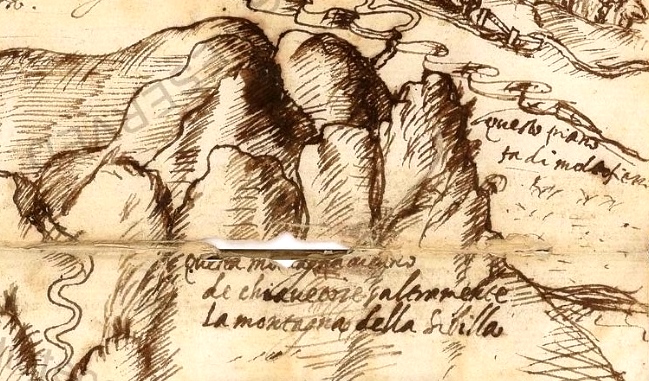

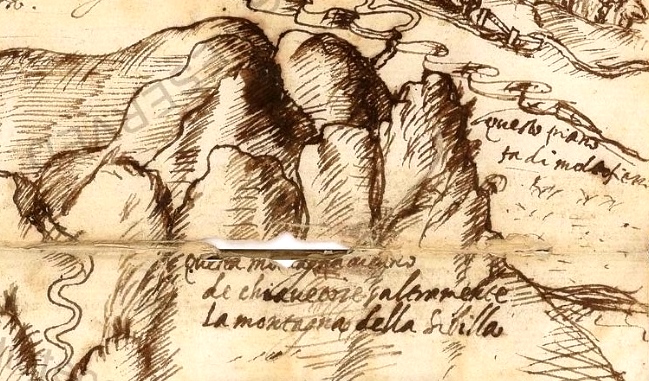

The Apennine Sibyl in a sixteenth-century vatican manuscript: the Mountain of the Sibyl

We finally get to the very core of the Sibyl's legend: the ancient manuscript shows a massive mountain stronghold, the Sibillini Range. A handwritten text indicates that “this mount is called the 'chiavetoie' (Vettore?), also known as The Mountain of the Sibyl”.

It is clear that the unknown draftsman depicts a sort of merger of Mount Vettore, Mount Sibyl and other peaks belonging to the Sibillini Range: they all get into one single giant cliff, where the Sibyl's mystery has carved its abode in secrecy.

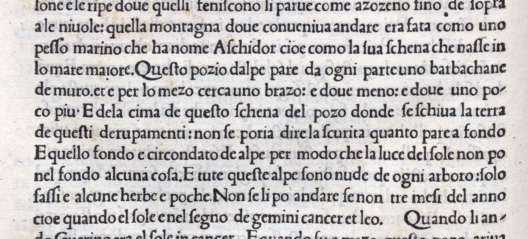

Looking at the precipices and ravines drawn by the map's unnamed author, our thoughts go back to the words written by Andrea da Barberino in his antique romance “Guerrino the Wretch”:

«This portion of the mountain looks like a walled barbican from all sides... And from the top of this ridge where the land brokens up in such ravines, one cannot tell the darkness that rules at the bottom. And that bottom is surmounted by lofty peaks so that no sunlight can reach any thing down there. And all those peaks are deprived of any trees; only rocks and scanty herbage».

La Sibilla Appenninica in un manoscritto vaticano del sedicesimo secolo: la Montagna della Sibilla

Siamo finalmente giunti al centro della leggenda della Sibilla: l'antico manoscritto ci presenta una grandiosa fortezza montuosa, il Massiccio dei Monti Sibillini. Una nota vergata dall'autore ci informa che “questa montagna dicono de chiavetoie, altramente La montagna della Sibilla”.

È chiaro che lo sconosciuto disegnatore ha inteso rappresentare una sorta di connubio tra il Monte Vettore, il Monte Sibilla e altre vette appartenenti ai Monti Sibillini: essi convergono tutti verso una sola gigantesca montagna, nella quale il mistero della Sibilla ha scavato in segreto la propria dimora.

Osservando i precipizi e i baratri tracciati dall'anonimo autore della mappa, i nostri pensieri corrono alle parole scritte da Andrea da Barberino nel suo antico romanzo “Guerrin Meschino”:

«Questo pozio d'alpe pare da ogni parte uno barbachane de muro et per lo mezo... E de la cima de questa schena del pozo donde seschiva la terra de questi dirupamenti; non se poria dire la scurità quanto pare a fondo. E quello fondo è circondato de alpe per modo che la luce del sole non po' nel fondo alcuna cosa. E tute queste alpe sono nude de ogni arboro; solo sassi e alcune herbe e poche».

25 Mar 2017

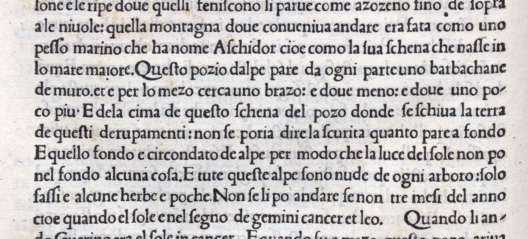

The Apennine Sibyl in a sixteenth-century vatican manuscript: necromancers by the Lakes of Pilatus

The vatican manuscript n° 5241 provides a stunning picture of one of Europe's eeriest places as it appeared in 1566: the Lakes of Pilatus, or - as the map calls it - the “Lake Avernus of Norcia”.

“Lake Avernus”: just like the magical lake near Naples, in the vicinity of the Cumaean Sibyl's cave, where the Latin poet Publius Vergilius Maro set the dreadful gateway to the nether world. In the “Guerrin Meschino” the Apennine Sibyl and the Cumaean Sibyl are the very same oracle («I was called chuman by the Romans...»), and in the map they are considered to be so close that their respective lakes bear the same name.

The unknown sixteenth-century draftsman depicts two lakes, with circles of stones laying between them, and people standing by. What does all that mean?

It means that we have the extraordinary chance to observe what used to happen up there, at the lakes set as small gems inside the very core of Mount Vettore: the map is our time-machine, or a camera shot which shows to us the action that once took place there, the way many ancient authors have already described to us.

«In the Apennine in the province of Norcia, a lake is found whose name is the Lake of Norcia» reports Leandro Alberti in his “Description of the entire Italy” in 1575, «this lake has a widespread renown among men, not only Italian but also foreigners, that demons may have their abode here and answer the questions that are submitted to them; men from far-off countries used to travel up to this place to consecrate their wicked, heinous books to the Devil... after drawing a circle on the ground...»

«A small islet is at the lake's center», wrote Antoine de La Sale after his journey to the lake in 1420, «made of a boulder which long ago was encircled by a wall; foundations of walls can still be seen in many spots. A narrow passageway goes from the shore to the small island, being some five feet under the water; I was told that by Pope's orders it had been ruined by the locals so as to prevent those who intended to reach the island to consecrate their books and summon the demons to find a way through».

The unnamed author of the map was there in 1566: an extremely rare trace of a legendary heritage that was strong in past centuries. Legends and lore that make our contemporary excursions to the Lakes of Pilatus even more thrilling and exciting, in a place whose picturesque fascination has beguiled men for hundreds and hundreds of years.

La Sibilla Appenninica in un manoscritto vaticano del sedicesimo secolo: i negromanti al Lago di Pilato

Il manoscritto vaticano n° 5241 ci restituisce una visione sorprendente di uno dei luoghi più sinistri d'Europa, così come esso appariva nel 1566: i Laghi di Pilato, o - come essi sono chiamati nella mappa - “il Laco Averno di Norcia”.

“Laco Averno”: esattamente come il magico lago che si trova in prossimità di Napoli, dove si apre la grotta della Sibilla Cumana, e dove il poeta latino Virgilio aveva posto il pauroso ingresso al mondo infero. Nel “Guerrin Meschino”, la Sibilla Appenninica non è altro che la Sibilla Cumana («io fui chiamata da Romani chumana...»), e anche in questa mappa esse sono considerate così simili che ai loro rispettivi laghi viene assegnato il medesimo appellativo.

Lo sconosciuto autore seicentesco della mappa disegna due laghi, con circoli di pietre situati nel mezzo, e alcuni personaggi sulle rive. Cosa significa tutto questo?

Significa che disponiamo oggi della straordinaria possibilità di osservare ciò che frequentemente accadeva in quelle contrade, presso quei laghi incastonati come piccole gemme all'interno dell'anfiteatro glaciale del Monte Vettore: la mappa è la nostra macchina del tempo, o anche un'immagine fotografica capace di mostrarci l'azione che un tempo si svolgeva in quei luoghi, nel modo esatto con il quale altri autori antichi ce lo hanno potuto descrivere.

«Nell'Apennino nel territorio Nursino, vi è il Lago, addimandato Lago di Norcia», scrive Leandro Alberti nella sua “Descrittione di tutta l'Italia” nel 1575. «Essendo volgata la fama di detto Lago appresso gli huomini non solamente d'Italia, ma fuori, cioè che quivi soggiornano i Diavoli, e danno risposta à chi li interroga, si mossero già alquanto tempo alcuni huomini di lontano paese, e vennero a questi luoghi per consagrare libri scelerati, e malvagi al Diavolo... havendo disegnato il circolo...».

«Un piccolo isolotto si trova nel centro del lago», scrisse Antoine de La Sale dopo il suo viaggio ai laghi nel 1420, «fatto di una roccia che un tempo era circondata da un muro; la base del muro è ancora visibile in molti punti. Uno stretto passaggio, sommerso dall'acqua per circa un metro e mezzo, conduce dalla riva alla piccola isola; mi è stato detto che per ordine del Papa è stato distrutto dalla gente del luogo per impedire il passaggio a coloro che intendevano raggiungere l'isola di consacrare i loro libri ed evocare i dèmoni».

Lo sconosciuto autore della mappa è stato qui nel 1566: una testimonianza estremamente rara relativa ad una tradizione leggendaria che è stata molto radicata negli scorsi secoli. Leggende e tradizioni che rendono le nostre moderne escursioni ancor più interessanti ed emozionanti, presso luoghi la cui pittoresca fascinazione ha ammaliato gli uomini per centinaia e centinaia di anni.

22 Mar 2017

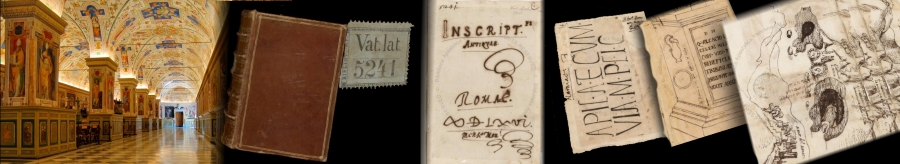

The Apennine Sibyl in a sixteenth-century vatican manuscript: a serendipitous finding

How can it be that an ancient map of Norcia, Mount Sibyl and the Lakes of Pilatus is included in a sixteenth-century collection of manuscripts? Who found it? And when?

When in 1980s Augusto Campana, a professor and illustrious member of the Vatican Apostolic Library, opened for the first time the leathered cover of the “codex” registered under the number 5241 in the Library's Latin section, his eyes opened wide in full amazement.

Among hundreds and hundreds of accurately drawn ancient Latin inscriptions - the collection of some unknown scholar who worked on it in 1566 - a strange diagram stood definitely out: a sort of 3D geographical map that showed a number of towns and mountainous features Mr. Campana knew very well. He was born in central Italy and he could but acknowledge the presence in the map of the mysterious, ancient enigmas of Mount Sibyl and the Lakes of Pilatus.

Following his serendipitous discovery, the map was first published in 1987, then reprinted in subsequent works by Romano Cordella, Maria Luciana Buseghin and others. This is the first time it is revealed in full detail and high-resolution scale.

Who was the sixteenth-century scholar who drew the map and put it in his collection of Roman inscriptions? Nobody can tell. And yet, one thing we have to take for granted: the unnamed draftsman was there for real, he drew what he actually saw, mountains and towns and lakes of the Sibillini Range.

In 1566, the Sibyl's legend was alive, and strong.

La Sibilla Appenninica in un manoscritto vaticano del sedicesimo secolo: una scoperta fortunata

Come è possibile che un'antica mappa di Norcia, del Monte Sibilla e dei Laghi di Pilato risulti compresa in una collezione di manoscritti cinquecenteschi? Chi fu a trovare quella mappa? E quando?

Quando, negli anni 1980, Augusto Campana, professore universitario e membro illustre della Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, aprì per la prima volta la copertina rilegata in cuoio del “codex” identificato con il numero 5241 nella sezione latina della Biblioteca, i suoi occhi si spalancarono per lo stupore.

In mezzo a centinaia e centinaia di antiche iscrizioni latine accuratamente riprodotte - la raccolta di uno sconosciuto studioso che aveva lavorato sulla collezione nel 1566 - si stagliava infatti uno strano diagramma: una sorta di mappa geografica tridimensionale, la quale mostrava città e rilievi montuosi che il Campana ben conosceva. Egli era infatti nato nell'Italia centrale, e non poté che riconoscere la presenza, all'interno della mappa, del misterioso, secolare enigma del Monte Sibilla e dei Laghi di Pilato.

Dopo quella casuale e fortunata scoperta, la mappa venne pubblicata per la prima volta nel 1987, e fu in seguito ristampata nei saggi a cura di Romano Cordella, Maria Luciana Buseghin e altri. Questa, però, è la prima volta che la mappa viene resa pubblica in alta risoluzione e con una elevatissima finezza di dettagli.

Chi era quello studioso del sedicesimo secolo che disegnò la mappa e la inserì nella propria collezione di antiche iscrizioni romane? Probabilmente, non lo sapremo mai. Ma c'è una cosa della quale possiamo dirci certi: lo sconosciuto autore del disegno aveva realmente visitato quei luoghi, egli aveva rappresentato ciò che aveva effettivamente veduto, montagne e città e laghi dei Monti Sibillini.

A quel tempo, nel 1566, la leggenda della Sibilla era viva, e potente.

19 Mar 2017

The Apennine Sibyl in a sixteenth-century vatican manuscript: Castelluccio and the Great Plain

The unknown author of the sixteenth-century map found in a manuscript at the Vatican Apostolic Library continued his venturesome journey: he left Norcia and ascended the ancient trail that led up to Mount Patino through the gorge of Capregna, until he finally got to the lost hamlet of Castelluccio.

The words he wrote on the map convey to our modern spirit all the astonished, bewildered feelings that seized his soul when he first saw the wide, almost endless extent of grassy land that waited for him in this remote corner of Italy: «the plain of Castelluccio - he says - it's two full miles without a single stone». A vision which still in our present days leaves men with their mouth agape.

In the map, the unnamed explorer draws a small party of riding men equipped with long spears heading to Castelluccio, which sits on its hillock overlooking the verdant plain. We may effectively figure out their emotions by reporting the words of another author, Father Fortunato Ciucci, who lived a century later:

«At its foot [of Mount Vettore] stands, on a charming hill named “the Paintings”, its graceful child: prosperous Castelluccio, dread of the wizards, watch over the appalling Cave of the Sibyl, adornment of the Mount, pleasure of the Countryside, crown to the Hills, abode of Goddesses, throne of half-gods, refreshment to the hearts, delight for the souls, delectation for the Peers and Field of Springtime; provided with water Springs, endowed with Grasslands, encircled by Woods and made strong by its Mount Vettore, which surmounts the village like a splendid Tower».

Certainly the latter are verbose, baroque expressions; and yet - as any lover of the place knows in his heart - they provide a perfect description of the magical spell which lives in Castelluccio. A spell that thoroughly enthralled both Father Ciucci and the unknown author of the vatican map.

La Sibilla Appenninica in un manoscritto vaticano del sedicesimo secolo: Castelluccio e il Pian Grande

L'ignoto autore della mappa cinquecentesca reperita in un manoscritto appartenente alla Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana continua il suo viaggio avventuroso: dopo avere lasciato Norcia, egli ascende l'antico sentiero che conduceva, attraverso la gola di Capregna, fino al Monte Patino, finché non raggiunge infine il borgo perduto di Castelluccio.

Le parole da lui vergate sulla mappa ci permettono oggi di percepire tutta la stupefatta meraviglia esperimentata da questo viaggiatore nel momento in cui, per la prima volta, viene a trovarsi di fronte alla distesa erbosa senza fine, nascosta in questo remoto angolo d'Italia: «il piano del Castelluccio - scrive - son due miglia senza una pietra». Una visione che anche ai nostri giorni lascia ogni visitatore a bocca aperta.

Nella mappa, l'esploratore senza nome disegna un piccolo drappello di uomini a cavallo, equipaggiati con lunghe lance, diretti verso Castelluccio, adagiato sulla piccola collina che domina la pianura verdeggiante. Possiamo rappresentarci adeguatamente le emozioni di questi viaggiatori richiamando le parole scritte da un altro autore, Padre Fortunato Ciucci, il quale visse nel secolo successivo:

«Tiene pié delle sue radici [del Monte Vettore] sopra un bellissimo colle chiamato le Pitture quel suo parto felice, il fortunatissimo Castelluccio, terror de' Maghi, guardia dell'orrenda Grotta Sibillina, bellezza del Monte, gioia della Campagna, corona de' Colli, Albergo delle Dee, Trono de' semidei, ristoro de' cori, allegrezza dell'alma, spasso de' Signori e Campo di Primavera; adorno de Fonti, arricchito de Prati, circondato di Selve e fortificato dal suo Monte Vittore, che quasi superba Torre li soprasta vicino».

Parole barocche e ridondanti, le quali però - come ben sa chi ama questi luoghi - ben descrivono l'atmosfera magica di Castelluccio, dalla quale sia il Ciucci che l'anonimo disegnatore furono totalmente stregati.

17 Mar 2017

The Apennine Sibyl in a sixteenth-century vatican manuscript: exploring Norcia

An ancient manuscript retrieved in the Vatican Apostolic Library renders a vision of Norcia as the town appeared to daring, adventurous visitors in 1566.

A road leads from the ancient hamlet of Cascia, visible in the background, to the town of St. Benedict. In the map, Cascia appears with its old name and character of “Castrum Cassiae”, surmounted by the stronghold built by Pope Paul II in 1465 (actually destroyed before the 1566).

Norcia itself is portrayed as a rich, walled city, with towers and domed churches - the latter a feature which is not confirmed by other sources.

Sure enough, the unknown traveller who sketched the map had really the chance to visit Norcia: the bellfry of the Basilica of St. Benedict, dominating the whole town, is just identical to the bell tower drawn by Dutch cartographer Ioannes Blaeu in his most famous sixteenth-century map (bottom image). Its elongated, pencil-like shape did not survive the appalling earthquakes that struck the town in 1703 and 1730, but still to occur when the Vatican drawing was sketched.

La Sibilla Appenninica in un manoscritto vaticano del sedicesimo secolo: l'apparizione di Norcia

Un antico manoscritto ritrovato presso la Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana ci fornisce una visione di Norcia, così come essa poteva mostrarsi al viaggiatore coraggioso ed intrepido che vi si fosse recato nel 1566.

Una strada conduce alla città di San Benedetto passando vicino all'antico insediamento di Cascia. Nella mappa, Cascia appare con il suo antico appellativo e aspetto di “Castrum Cassiae”, sormontato dalla fortezza costruita da Papa Paolo II nel 1465 (in realtà distrutta prima del 1566).

La stessa Norcia è raffigurata come una città ricca, circondata da mura, con torri e chiese dal tetto a cupola - circostanza, quest'ultima, non confermata da altre fonti.

Certamente, però, lo sconosciuto viaggiatore che disegnò la mappa deve avere realmente avuto la possibilità di visitare Norcia: infatti il campanile della Basilica di San Benedetto, che domina l'interà città, è esattamente identico alla torre campanaria disegnata dal cartografo olandese Ioannes Blaeu nella sua famosissima mappa seicentesca (immagine in fondo). La sua forma allungata, a matita, non sopravvisse ai terrificanti terremoti che colpirono la città nel 1703 e 1730, non ancora avvenuti al momento della realizzazione del disegno vaticano.

16 Mar 2017

EXCLUSIVE: “The Apennine Sibyl - A Mystery and a Legend” releases high-definition image of sixteenth century drawing of Mount Sibyl and the Lakes of Pilatus from Vatican manuscript

Rome, the Vatican, the Apostolic Library, an ancient manuscript that unexpectedly unveils its hidden treasure: the legend of the Apennine Sibyl suddenly appears amid a collection of hundreds of handwritten sheets dedicated to antique Roman inscriptions, dating to the sixteenth century.

In 1566, a detailed cartographic map of the Sibillini Mountain Range was sketched by an unknown hand belonging to a man who lived in the late Renaissance: Norcia, Castelluccio, Montemonaco, Mount Sibyl, the Lakes of Pilatus emerge from the codex as if it had been written in our present days. This is an outstanding example of the vigour of the Sibyl's legend and the magical renown of the Sibillini Range across the centuries.

For the first time ever, “The Apennine Sibyl - A Mystery and a Legend” is proud to present a high-definition copy of the manuscripted pages. The map has already been published in earlier publications, but only in black-and-white, smaller-scale printing.

This is a significant contribution to the study of the sibilline legend we have the pleasure to present today to a wider audience, by releasing a number of dedicated posts that will come after this first one in the next days. A unique, unprecedented occasion only available on “The Apennine Sibyl - A Mystery and a Legend”.

ESCLUSIVO: "Sibilla Appenninica - Il Mistero e la Leggenda" pubblica l'immagine in alta definizione del disegno risalente al sedicesimo secolo del Monte Sibilla e dei Laghi di Pilato tratto da un prezioso manoscritto vaticano

Roma, il Vaticano, la Biblioteca Apostolica, un antico manoscritto che rivela inaspettatamente il suo tesoro segreto: la leggenda della Sibilla Appenninica appare improvvisamente all'interno di una collezione di centinaia di schizzi realizzati a mano dedicati alle antiche epigrafi latine, databile al sedicesimo secolo.

Nel 1566, una mano ignota, appartenente ad un uomo del tardo Rinascimento, ha tratteggiato una dettagliata cartografia dei Monti Sibillini: Norcia, Castelluccio, Montemonaco, il Monte Sibilla e i Laghi di Pilato emergono dal codice con una freschezza quasi contemporanea. Si tratta di una testimonianza significativa del vigore del mito della Sibilla e della magica fama dei Monti Sibillini attraverso i secoli.

"Sibilla Appenninica - Il Mistero e la Leggenda" è orgogliosa di presentare, per la prima volta in assoluto, una immagine in alta definizione delle pagine manoscritte. La mappa è già stata pubblicata in precedenza, ma solamente in bianco e nero e con una definizione significativamente inferiore.

Abbiamo dunque il piacere di presentare oggi ad un pubblico più vasto questo importante contributo agli studi sulla leggenda sibillina, pubblicando una serie di post dedicati a questo tema, e che seguiranno nei prossimi giorni quello che state leggendo. Un'occasione di approfondimento unico disponibile esclusivamente su "Sibilla Appenninica - Il Mistero e la Leggenda".

4 Oct 2016

Castelluccio and the French scientists in search of the Sibyl / 2

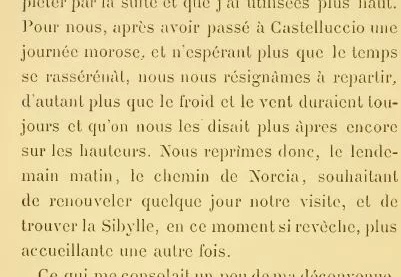

In 1897, Gaston Paris, a famous French philologist, undertook a journey to Mount Sibyl, in Italy, but he was forced to stop in Castelluccio. His words seem to depict today's Pian Grande:

«After passing a somber day in Castelluccio and having lost all hopes for the sky to brighten up, we resolved to depart. Our decision was made easier by the tirelessness of the icy wind which was expected to be the more stronger on the peaks. The next morning we retraced our steps towards Norcia, wishing we might be back in a future time, when we might find the Sibyl - now so embittered and unkind to us - in a more welcoming mood».

[Original French version: «après avoir passé à Castelluccio une journée morose, et n'espérant plus que le temps se rassérénât, nous nous résignâmes à repartir, d'autant plus que le froid et le vent duraient toujours et qu'on nous les disait plus âpres encore sur les hauteurs. Nous reprîmes donc, le lendemain matin, le chemin de Norcia, souhaitant de renouveler quelque jour notre visite, et de trouver la Sibylle, en ce moment si revéche, plus accueillante une autre fois»]

Castelluccio e gli scienziati francesi in cerca della Sibilla /2

Nel 1897, Gaston Paris, il famoso filologo francese, intraprese un viaggio verso il Monte Sibilla; egli fu costretto però a fermarsi a Castelluccio. E le sue parole sembrano descrivere il Pian Grande dei nostri giorni:

«dopo avere trascorso a Castelluccio una giornata uggiosa, e non potendo sperare in un rasserenamento del tempo, ci rassegnammo a ripartire, anche perché il freddo e il vento continuavano ancora e, ci dicevano, sarebbero risultati ancora più intensi in altitudine. Riprendemmo dunque, l'indomani mattina, il cammino verso Norcia, augurandoci di poter rinnovare un giorno la nostra visita, e di trovare la Sibilla, in quel momento così ostile, più accogliente in un prossimo futuro».

4 Ott 2016

Castelluccio and the French scientists in search of the Sibyl

In June 1897, philologist Gaston Paris left France to reach Castelluccio on the footsteps of the Sibyl's legend. The following is a fresh account of his arrival to the Great Plain, together with his Italian colleague and friend Pio Rajna:

«We journeyed at a slow pace across the 'pian grande', a true glory of Castelluccio. That is an expanse of grassland, which has retained the smooth appearance - so unfrequent at this elevation - of the lake that once was there and it seems to re-create itself from time to time under the blanket of the snow: it is covered by a thick carpet of green grass which, under the sunlight, takes on a pale emerald glaze typical of the grassy highlands. On the very edge of this vast plateau, a rocky hillock is visible - in the form of a reversed hoof - on whose top stands Castelluccio. This 'small nasty castle' (this is the meaning of the word 'Castelluccio'), once a papal stronghold, is just a dilapidated hamlet in the present days. We got there frozen stiff, and we were absolutely happy to warm up in the kitchen of the welcoming house of Mr. Calabresi, the landlord of the region, who was so kind as to open his place to us, courtesy of the ever caring attitude of our friend, Pio Rajna...».

[Original French version: «...nous traversons lentement le piano grande qui fait l'orgueil de Gastelluccio. C'est une immense prairie, qui a conservé l'égalité de surface, bien rare à cette altitude, du lac qu'elle était jadis et qu'elle redevient à la fonte des neiges; elle est couverte d'un épais lapis de velours vert qui, sous les nuages gris de ce jour, apparaît mat et foncé, mais qui prend au soleil les transparences d'émeraude pâle des gazons alpestres. Tout au bout de cette vaste plaine se dresse le rocher, en forme de sabot renversé, dont Castelluccio occupe le haut. Ce « mauvais petit château» (c'est le sens propre de Caslelluccio), jadis forteresse papale, est aujourdhui un pauvre village. Nous y arrivons tout transis, et nous sommes heureux de nous réchauffer dans la cuisine de la maison hospitalière que M. Calabresi, le grand propriétaire du pays, a bien voulu, — toujours grâce aux soins vigilants de notre ami Rajna, — mettre à notre disposition...».]

Castelluccio e gli scienziati francesi in cerca della Sibilla

Nel giugno del 1897, il filologo Gaston Paris partì dalla Francia per recarsi a Castelluccio in cerca della Sibilla. Ed ecco il vivace, freschissimo resoconto del suo arrivo al Pian Grande, assieme al suo amico e collega Pio Rajna:

«... Traversammo lentamente il 'piano grande', che costituisce l'orgoglio di Castelluccio. È una prateria immensa, la quale ha conservato l'uniformità di superficie - molto rara a queste altitudini - del lago che vi era una volta e che periodicamente sembra riformarsi sotto le coltri di neve: è coperta da uno spesso tappeto di velluto verde il quale, sotto il manto grigio di nuvole, sembra scuro ed opaco, ma che assume ai raggi del sole la luminosità pallidamente smeraldina dei prativi alpestri. Proprio sul limitare di questa vasta pianura si erge la mole rocciosa - in forma di zoccolo rovesciato - del quale Castelluccio occupa la cima. Questo 'piccolo castello cattivo' (questo è il significato della parola 'Castelluccio'), un tempo fortezza pontificia, è oggi un povero villaggio. Noi siamo giunti lì quasi congelati, e siamo stati ben felici di poterci riscaldare nella cucina dell'ospitale abitazione che il Signor Calabresi, il grande proprietario del luogo, ha voluto mettere a nostra disposizione grazie alle cure sempre attente del nostro amico Pio Rajna...».

16 Sep 2016

A rumour runs across the Sibillini Range

In the early fifteenth century, a rumour had spread - in the cragged mountain ridges raising in the vicinity of Norcia, between the Umbrian hills and the Adriatic sea, amid the dreadful abysses and ravines, somewhere in the middle of this desolate and frightful scenery - that an enchantress, a fairy queen had established her dwelling; and the peasants called her by the name of SIBYL.

Una voce che corre tra le vette dei Sibillini

All'inizio del quindicesimo secolo, una strana dicerìa si era diffusa tra le vette impervie poste nelle vicinanze di Norcia, tra le colline umbre ed il mare Adriatico, in mezzo agli spaventosi precipizi di roccia. Si diceva che, da qualche parte, proprio nel mezzo di quel panorama così remoto e desolato, avesse stabilito la propria dimora un'incantatrice, una regina semidivina: e i contadini del luogo la chiamavano con l'appellativo di SIBILLA.

17 Aug 2016

Gaston Paris, a French philologist in search of the Sibyl

The riveting chronicle of the journey to Norcia and Mount Sibyl attempted by French philologist Gaston Paris in 1897 and achieved by his Italian colleague Pio Rajna.

Gaston Paris, un filologo francese in cerca della Sibilla

L'entusiasmante cronaca di un viaggio a Norcia e al Monte della Sibilla tentato dal filologo francese Gaston Paris nel 1897, ed effettuato poi dal suo collega italiano Pio Rajna.