14 Giu 2020

Montemonaco e il Monte della Sibilla in una mappa del diciassettesimo secolo

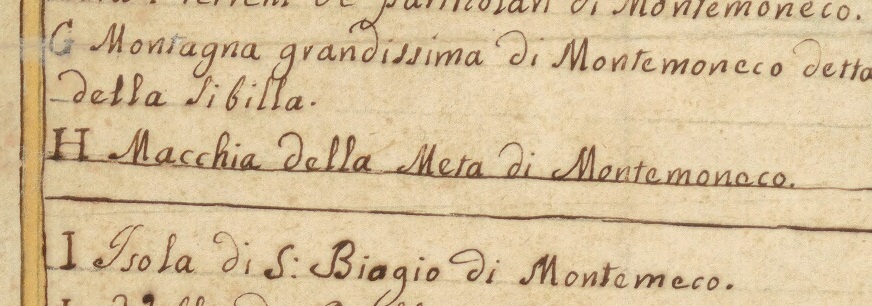

In questa bellissima e rarissima immagine settecentesca, realizzata a china e acquerello, conservata presso l'Archivio di Stato di Roma, è visibile l'antico borgo di Montemonaco, con i suoi palazzi e le sue chiese.

E, accanto, sulla sinistra, ecco quella che il cartiglio laterale indica come la "montagna grandissima di Montemonaco detta della Sibilla". Il fascino di una leggenda che riemerge dalle testimonianze del tempo, anche dalle carte meno conosciute.

(Roma, Archivio di Stato, Collezioni disegni e mappe - Collezione I, segnatura: 45 - 168 / 1)

12 Nov 2018

Mount Sibyl - At last, after twenty years, new geological surveys are about to take place at the Sibyl's cave

The Apennine Sibyl, a legendary tale which for many centuries has attracted people from all European countries to a remote cliff in the Italian Sibillini Mountain Range, is now back in the spotlight of scientific, media and public attention.

While a new docufiction on the Sibyl is currently undergoing postproduction (“The Oracle - Between Legend and Truth” by Italian filmmaking firm Sydonia), a thrilling announcement was released just a few days ago: with the support of the Regione Marche, the Municipality of Montemonaco and the University of Camerino, a new exploration campaign will be launched on the top of Mount Sibyl, at the very spot where the Sibyl's cave lies.

The last activities performed on the Sibyl's mountain-top were promoted by Centro Culturale Elissa in the summer of year 2000, with the performance of a geognostic survey based on a ground-penetrating radar, which detected «vast underground cavities 50 feet below the surface, an intricacy of convoluted galleries with an overall length of some 170 yards».

Now, the new campaign will proceed from the results obtained nearly twenty years ago, with the performance of a most remarkable follow-up phase: drilling operations will be carried out by the Sibyl's cave on the locations already tracked by the ground-penetrating radar, with holes being pierced in the rocky soil with a maximum diameter of 6 inches. The hunt for the subterranean cavities hidden beneath the cliff of Mount Sibyl has just started.

The survey operations, funded by Regione Marche and Municipality of Montemonaco with Euro 50,000, will be filmed and the drilled holes explored with camera probes. The resulting footage will be used for the making of a documentary by Tullio Bernabei, a journalist, speleologist and filmmaker who collaborates with RAI, the Italian national broadcaster, in the production of popular TV series including “GEO”, “Kilimangiaro”, and “Ulisse”.

According to ANSA news agency, the scientific aspects of the project will be managed by Piero Farabollini, a professor at the University of Camerino and recently appointed as the Special Commissioner of the Italian government for the 2016 Earthquake Reconstruction.

A new, fresh wave of interest is arising about the Apennine Sibyl's legend and lore: a sign that this remote Italian corner, in which the Sibillini Mountain Range raises its lofty peaks, is still capable of generating a strong attractiveness for contemporary tourism, through scientific research and the recovery of a literary tradition that had been almost forgotten, by both residents and local administrations.

A token of hope, especially in the current strait which are marked by a long, arduous reconstruction track following the earthquake that struck the region in 2016.

Monte della Sibilla - Finalmente, dopo quasi venti anni, saranno effettuate nuove prospezioni geologiche presso la grotta della Sibilla

La Sibilla Appenninica, il racconto leggendario che per molti secoli ha attirato visitatori da ogni angolo d'Europa fino a una remota cima appartenente al massiccio dei Monti Sibillini, è oggi tornata al centro dell'attenzione di scienziati, organi di informazione e grande pubblico.

In attesa della nuova docufiction sulla Sibilla, attualmente in fase di postproduzione ("Sibilla - Tra Verità e Leggenda", che sarà rilasciato dalla casa di produzione marchigiana Sydonia), nei giorni scorsi è stato diffuso un nuovo entusiasmante annuncio: con il supporto di Regione Marche, Comune di Montemonaco e Università di Camerino, una nuova campagna di esplorazione sarà lanciata sulla vetta del Monte Sibilla, nel luogo dove si trova l'ingresso della grotta sibillina.

Le ultime attività di ricerca effettuate sulla cima della Sibilla furono promosse dal Centro Culturale Elissa nell'estate del 2000, con il completamento di una serie di indagini geognostiche basate sulla tecnica del georadar, attraverso le quali fu possibile rilevare «l'esistenza di un vasto complesso ipogeo alla profondità di 15 metri sotto il piano di campagna, fatto di cunicoli labirintici, notevoli cavità e della lunghezza di circa 150 m».

Ora la nuova campagna proseguirà le ricerche sulla base dei risultati ottenuti quasi venti anni fa, con l'effettuazione della successiva fase di fondamentale rilevanza: saranno infatti condotte perforazioni in prossimità della grotta della Sibilla, nei punti già segnalati ai ricercatori dal georadar, con fori che saranno praticati, nel suolo roccioso, con un diametro massimo di 15 centimetri. La caccia alle cavità sotterranee che si celano al di sotto del picco del Monte Sibilla è dunque cominciata.

Inoltre, le indagini scientifiche, finanziate dalla Regione Marche e dal Comune di Montemonaco con 50.000 Euro, saranno documentate audiovisivamente e le perforazioni indagate con opportune telecamere. Il materiale girato sarà utilizzato per la realizzazione di un documentario prodotto dal giornalista, speleologo e regista Tullio Bernabei, noto per le sue collaborazioni con RAI nell'ambito della realizzazione di popolari prodotti televisivi quali “GEO”, “Kilimangiaro” e “Ulisse”.

Secondo quanto riferisce l'agenzia ANSA, gli aspetti scientifici del progetto saranno coordinati da Piero Farabollini, professore presso l'Università di Camerino, recentemente nominato Commissario Straordinario per la Ricostruzione Sisma 2016.

Una nuova ondata di interesse nei confronti delle leggende legate alla Sibilla Appenninica si sta dunque manifestando: un segno che questo remoto angolo d'Italia, nel quale si ergono i vertiginosi picchi dei Monti Sibillini, è ancora capace di esercitare una rilevante attrazione nei confronti del turismo contemporaneo, attraverso la ricerca scientifica e il recupero di una tradizione letteraria che era stata quasi del tutto dimenticata, sia dai residenti che dalle pubbliche amministrazioni locali.

Un segnale di speranza, anche e soprattutto in questi tempi difficili caratterizzati da un lungo e doloroso percorso ricostruttivo post-terremoto.

11 Aug 2017

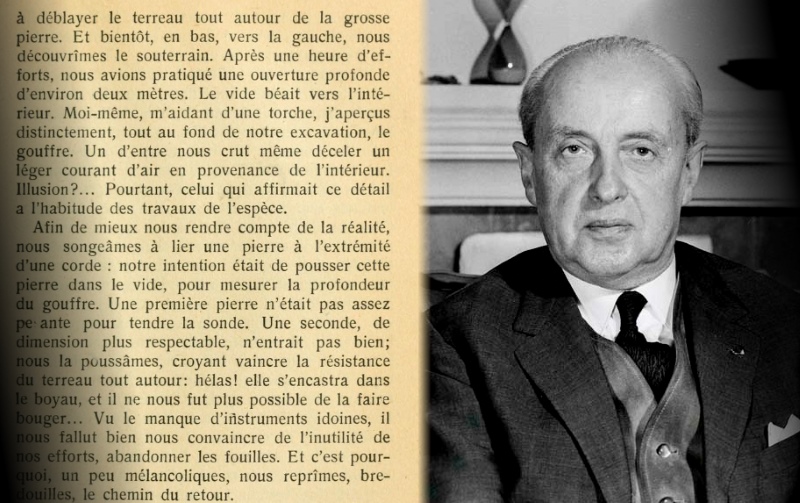

Diggers at the Sibyl's cave: an account by Fernand Desonay /2

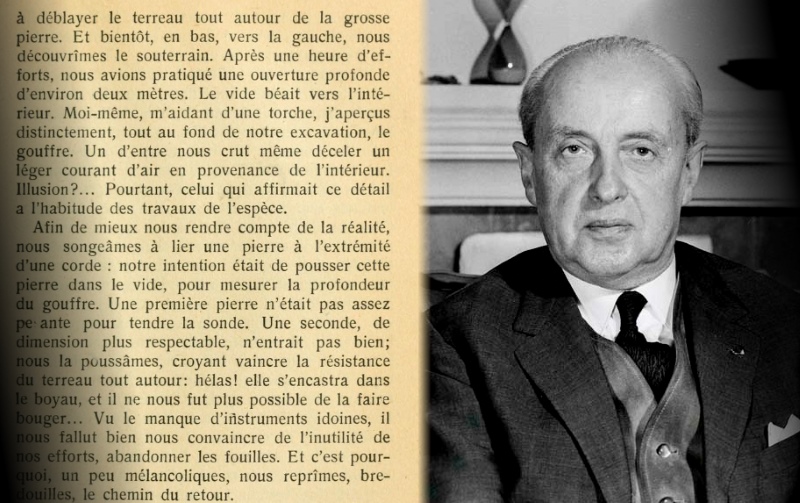

As we detailed in preceding posts, Fernand Desonay, the Belgian professor who issued scientific editions of the works by Antoine de La Sale, took part into different digging expeditions to Mount Sibyl. In 1953, he joined an official campaign led by Giovanni Annibaldi, during which most promising results were achieved. However, he had already been on the Sibyl's mountain-top, both in 1929 and 1930, with small parties of digging friends. At that time, the results were very limited owing to the total lack of skilled workforce and essential tools.

Let's continue with the description he provided as to the small 1930 expedition:

«... And soon, down and on the left side, we uncovered the underground hollow. After efforts lasting an hour , we had carved an aperture some three feet deep. The chasm gaped towards the inner portion of the cave. I myself, using a torchlight, distinctly saw, at the very bottom of our excavation, an abyss. A member of our party also thought he could feel a faint whiff of air coming out from the inside. Just an illusion?... Yet the person who felt that is used to this kind of works.

To gain a better insight into the actual situation, we tried to attach a stone to the far end of a rope: our intention was to hurl the stone into the void so as to ascertain the depth of the abyss. A first rock was not heavy enough to stretch the rope. A second one, of more remarkable size, did not fit into the hole; we pushed it in place, hoping we would win the opposition of the ground nearby: unfortunately enough, the rock got stuck in the gaping void, and we weren't able to set it free... owing to the lack of any effective tool, we had to make up our minds that our efforts were all in vain, and that we had to abandon our excavations. As a result, in low spirits and with pensive attitudes, we retraced our steps to the valley».

Despite the unsuccessful attempt, Fernand Desonay would have a new chance to explore the mystery of the Sibyl. That will occur twenty-three years later, when he will reach the mountain-top once again, together with Mr. Annibaldi and his well-equipped team.

[in the original French text: «Et bientôt, en bas, vers la gauche, nous découvrîmes le souterrain. Après une heure d'efforts, nous avions pratiqué une ouverture profonde d'environ deux mètres. Le vide béait vers l'intérieur. Moi même, m'aidant d'une torche, j'aperçus distinctement, tout au fond de notre excavation, le gouffre. Un d'entre nous crut même déceler un léger courant d'air en provenance de l'intérieur. Illusion?... Pourtant, celui qui affirmait ce détail a l'habitude des travaux de l'espèce.

Afin de mieux nous rendre compte de la réalité, nous songeâmes à lier une pierre à l'extrémité d'une corde: notre intention était de pousser cette pierre dans le vide, pour measurer la profondeur du gouffre. Une première pierre n'était pas assez pesante pour tendre la sonde. Une seconde, de dimensions plus respectables, n'entrait pas bien; nous la poussâmes, croyant vaincre la résistance du terreau tout autour: hélas! elle s'encastra dans le boyau, et il ne nous fut possible de la faire bouger... Vu la manque d'instruments idoines, il nous fallut bien nous convaincre de l'inutilité de nos efforts, abandonner les fouilles. Et c'est pourquoi, un peu mélancoliques, nous reprîmes, bredouilles, le chemin du retour.»]

Scavi e scavatori alla grotta della Sibilla: un racconto di Fernand Desonay /2

Come abbiamo già avuto modo di illustrare in precedenti post, Fernand Desonay, il filologo belga che aveva curato le edizione critiche delle opere di Antoine de La Sale, prese parte a diverse campagne di scavo effettuate sul Monte Sibilla. Nel 1953, aveva infatti partecipato ad una spedizione ufficiale guidata da Giovanni Annibaldi, nel corso della quale vennero reperiti risultati estremamente interessanti. In realtà, egli era già stato sulla cima della Sibilla, sia nel 1929 che nel 1930, assieme ad un piccolo gruppo di amici. A quell'epoca, i risultati degli scavi furono molto limitati, a causa della totale mancanza sia di operai specializzati che di idonee attrezzature di scavo.

Continuiamo dunque con la descrizione lasciataci da Desonay relativamente alla piccola spedizione del 1930:

«...E poco dopo, in basso, sulla sinistra, riuscimmo a scoprire il sotterraneo. Dopo un'ora di sforzi, eravamo riusciti a praticare una apertura profonda circa due metri. La cavità si apriva verso l'interno. Io stesso, aiutandomi con una torcia, potei distinguere distintamente, proprio in fondo al nostro scavo, l'abisso. Uno di noi credette addirittura di percepire una leggera corrente d'aria che proveniva dall'interno. Illusione?... Bisogna dire che colui che sosteneva questo dettaglio era uso a lavori di questo genere.

Per meglio renderci conto delle reali condizioni, pensammo di legare una pietra all'estremità di una corda: la nostra idea era quella di spingere questa pietra nel foro, per poter misurare la profondità dell'abisso. Una prima pietra non risultò essere sufficientemente pesante da poter tendere la corda. Una seconda, di dimensioni maggiormente rispettabili, non entrava affatto facilmente: allora la spingemmo, credendo di poter vincere la resistenza del terreno tutt'attorno: ma, disdetta!, essa si incastrò nel buco, e non fu possibile farla muovere in alcun modo. Vista la mancanza di strumenti idonei, dovemmo forzatamente renderci conto dell'inutilità dei nostri sforzi, e abbandonare gli scavi. Ed ecco perché, un poco malinconici e molto pensierosi, non ci restò che riprendere la via del ritorno».

Malgrado l'infruttuoso tentativo, Fernand Desonay avrà un'ulteriore opportunità di esplorare il mistero della Sibilla. Ciò accadrà ventitré anni dopo, quando lo studioso raggiungerà nuovamente la cima della montagna, assieme ad Annibaldi e alla sua squadra ben equipaggiata.

[nel testo originale francese: «Et bientôt, en bas, vers la gauche, nous découvrîmes le souterrain. Après une heure d'efforts, nous avions pratiqué une ouverture profonde d'environ deux mètres. Le vide béait vers l'intérieur. Moi même, m'aidant d'une torche, j'aperçus distinctement, tout au fond de notre excavation, le gouffre. Un d'entre nous crut même déceler un léger courant d'air en provenance de l'intérieur. Illusion?... Pourtant, celui qui affirmait ce détail a l'habitude des travaux de l'espèce.

Afin de mieux nous rendre compte de la réalité, nous songeâmes à lier une pierre à l'extrémité d'une corde: notre intention était de pousser cette pierre dans le vide, pour measurer la profondeur du gouffre. Une première pierre n'était pas assez pesante pour tendre la sonde. Une seconde, de dimensions plus respectables, n'entrait pas bien; nous la poussâmes, croyant vaincre la résistance du terreau tout autour: hélas! elle s'encastra dans le boyau, et il ne nous fut possible de la faire bouger... Vu la manque d'instruments idoines, il nous fallut bien nous convaincre de l'inutilité de nos efforts, abandonner les fouilles. Et c'est pourquoi, un peu mélancoliques, nous reprîmes, bredouilles, le chemin du retour.»]

5 Aug 2017

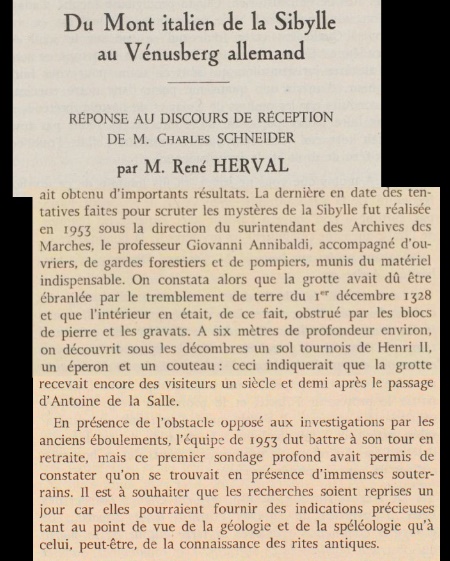

Diggers at the Sibyl's cave: 1953 excavations

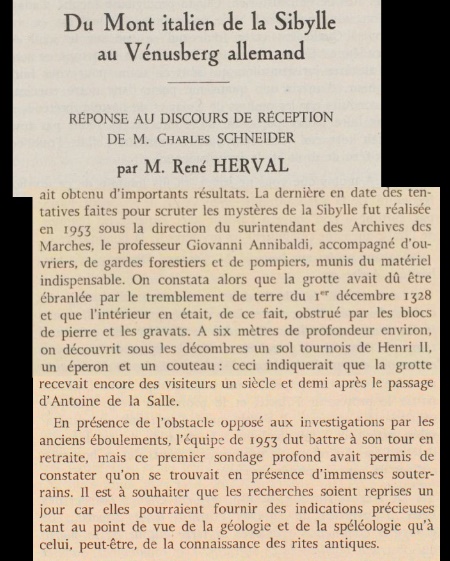

Following two passionate speeches on the Apennine Sibyl's legend delivered by Fernand Desonay in Rome at the beginning of 1953, a new official digging expedition moved to the Sibillini Range in the summer of that same year. It was led by Giovanni Annibaldi, the Director General of the Department of Antiquities of Marche, and included Fernand Desonay and Domenico Falzetti as team members.

It was no small party: there were «workers, forest rangers, firefighter, equipped with all the essential devices», as reported in a description by René Herval, “From Mount Sibyl in Italy to the German Venusberg”.

«They ascertained that the cavern had been possibly shaken by the earthquake that hit the region on 1st December 1328», added Mr. Herval, «and that the inner part was in consequence obstructed by the collapsed boulders and debris. At a depth of some eighteen feet, they found beneath the rubble a Tournois coin of Henry II, a spur and a knife. This trove should point to the fact that the cave still accommodated visitors a century and a half after Antoine de La Sale's excursion».

«Owing to the obstruction caused by the ancient subsidence which prevented further investigation, the 1953 team had to give up and withdraw [as it had already happened in 1930]; yet this first deep probing activity had resulted in the detection of extended subterranean hollows.»

As ever, the Sibyl eluded any attempts to break into her cave and unveil her long-preserved secret.

[in the original French text: «La dernière en date des tentatives faites pour scruter les mystères de la Sibylle fut réalisée en 1953 sous la direction du surintendant des Archives des Marches, le professeur Giovanni Annibaldi, accompagné d'ouvriers, de gardes forestiers et de pompiers, munis du materiél indispensable. On constata alors que la grotte avait dû être ébranlée par le tremblement de terre du 1er décembre 1328 et que l'intérieur en était, de ce fait, obstrué par les blocs de pierre et les gravats. A six mètres de profondeur environ, on découvrit sous les décombres un sol tournois de Henri II, un éperon et un couteau: ceci indiquerait que la grotte recevait encore des visiteurs un siècle et demi après le passage d'Antoine de la Salle.

En présence de l'obstacle opposé aux investigations par les anciens éboulements, l'équipe de 1953 dut battre à son tour en retraite, mais ce premier sondage profond avait permis de constater qu'on se trouvait en présence d'immenses souterrains.»]

Scavi e scavatori alla grotta della Sibilla: la campagna del 1953

Dopo due appassionate conferenze sulla leggenda della Sibilla Appenninica tenute da Fernand Desonay a Roma all'inizio del 1953, nell'estate di quello stesso anno venne organizzata, sui Monti Sibillini, una nuova campagna di scavi. La campagna era guidata da Giovanni Annibaldi, il Soprintendente alle Antichità delle Marche, e di essa facevano parte Fernand Desonay e Domenico Falzetti.

Non si trattava di un piccolo gruppo: vi erano infatti «operai, guardie forestali e vigili del fuoco, muniti del materiale indispensabile», come riferito da René Herval nel suo documento "Du Mont italien de la Sibylle au Vénusberg allemand".

«Si constatò allora che la grotta aveva dovuto subire le scosse del terremoto del 1 dicembre 1328», aggiunge Herval, «e che, a causa di questo fatto, l'interno ne era stato ostruito da blocchi di pietra e detriti. A circa sei metri di profondità, sotto i crolli, furono scoperti un soldo tornese di Enrico II, uno sperone e un coltello: ciò indicherebbe che la grotta riceveva ancora visitatori un secolo e mezzo dopo il passaggio di Antoine de la Salle».

«A causa dell'ostacolo opposto alle investigazioni dagli antichi cedimenti, la squadra del 1953 fu costretta a battere a propria volta in ritirata [come già era accaduto nel 1930], ma questo primo sondaggio profondo aveva permesso di constatare come ci si trovasse in presenza di immensi sotterranei.»

Come sempre, la Sibilla aveva eluso ogni tentativo di penetrare nella sua grotta e di svelare il suo segreto preservato da secoli.

[nel testo originale francese: «La dernière en date des tentatives faites pour scruter les mystères de la Sibylle fut réalisée en 1953 sous la direction du surintendant des Archives des Marches, le professeur Giovanni Annibaldi, accompagné d'ouvriers, de gardes forestiers et de pompiers, munis du materiél indispensable. On constata alors que la grotte avait dû être ébranlée par le tremblement de terre du 1er décembre 1328 et que l'intérieur en était, de ce fait, obstrué par les blocs de pierre et les gravats. A six mètres de profondeur environ, on découvrit sous les décombres un sol tournois de Henri II, un éperon et un couteau: ceci indiquerait que la grotte recevait encore des visiteurs un siècle et demi après le passage d'Antoine de la Salle.

En présence de l'obstacle opposé aux investigations par les anciens éboulements, l'équipe de 1953 dut battre à son tour en retraite, mais ce premier sondage profond avait permis de constater qu'on se trouvait en présence d'immenses souterrains.»]

23 Jul 2017

Diggers at the Sibyl's cave: an account by Fernand Desonay /1

Belgian philologist Fernand Desonay took part in various excavation campaigns on the Sibyl's mountain-top. In 1930 he wrote a thrilling firsthand report on the digging activity carried out on the cliff. Here is what he found there:

«The subsequent year I had the chance to pay a second, more rewarding visit to the cave set amid the Apennines, together with a few of my Italian friends, between 15 and 18 August 1930. Our small party left Norcia on the morning of August, 15th. The next day, we reached a shepherd's bivouac at 5.400 feet on the mountain. On August 17th, we attained the cavern, at eight in the morning. What a remarkable peace around the Sibyl's peak, in the vicinity of the paradise!...

The cave had been turned thoroughly upside down. Recent excavation works had utterly changed its outward aspect. The underground cavity had completely disappeared. We could see some heaps of fragmented rocks. The clumsy diggers, considering the hard exertion they had undergone, might even have achieved a minimal result, had they followed with more resolute confidence the marks of the ancient hollow rather than digging in the wrong direction. A huge boulder of rock, once rolled before the cave's entrance by superstitious shepherds, now was set free altogether; its appearance was not that of a stone formerly in place.

My friends and I began to clear the ground around the large boulder. And soon, down and on the left side, we uncovered the underground hollow...»

[in the original French text: «L'année suivante, j'eus l'occasion de faire, en compagnie de quelques amis italiens, entre le 15 et le 18 août 1930, une seconde visite, plus fructueuse, à la grotte de l'Apennin. Notre petite troupe avait quitté Norcia dans la matinéé du 15 août. Le 16, nous nous trouvions dans un campement de bergers, à l'altitude de 1800 mètres. Le 19 [erroné pour le 17 - note du rédacteur] au matin, nous attegnions la grotte, vers le 8 heures. Quelle paix autour de la Sibylle, dans le voisinage du paradis!...

La caverne était sens dessus dessous. De récents travaux d'exploration en avaient complètement modifié l'habitus. Masquèe l'ouverture du souterrain. On distinguait quelques amas de pierres gluantes. Les fouilleurs inexpérimentés, vu la peine qu'ils s'étaient donnée, auraient peut-être réussi à découvrir quelque chose si, au lieu de prendre une mauvaise direction, ils avaient suivi avec plus de confiance le tracé de l'antique terrier. Un gros quartier de roche, que des bergers superstitieux avaient fait rouler autrefois devant l'ouverture, se trouvait complètement mis à nu; son aspect n'était pas celui d'une pierre de rapport.

Mes compagnon et moi, nous commençâmes à déblayer le terreau tout autour de la grosse pierre. Et bientôt, en bas, vers la gauche, nous découvrîmes le souterrain....»]

Scavi e scavatori alla grotta della Sibilla: un racconto di Fernand Desonay /1

Il filologo belga Fernand Desonay partecipò a varie campagne di scavo effettuate sul picco del Monte Sibilla. Nel 1930, egli scrisse questa emozionante relazione a proposito delle attività di ricerca condotte sulla cima. Ecco, nel suo racconto, cosa trovò all'epoca:

«L'anno successivo, ebbi l'occasione di fare, in compagnia di alcuni amici italiani, tra il 15 e il 18 agosto 1930, una seconda visita, più fruttuosa, alla grotta dell'Appennino. Il nostro piccolo gruppo aveva lasciato Norcia la mattina del 15 agosto. Il 16, ci trovammo presso un bivacco di pastori, a 1800 metri di altitudine. Il 17, di mattina, giungemmo infine alla grotta, verso le otto. Che pace attorno alla Sibilla, in prossimità del paradiso!...

La grotta era del tutto sottosopra. Recenti lavori di scavo ne avevano modificato completamente l'aspetto. L'apertura del sotterraneo ricoperta. Si notavano alcuni ammassi di pietre frantumate. Gli inesperti scavatori, considerata la pena che si erano data, sarebbero anche riusciti a scoprire qualcosa, se solo avessero seguito con maggiore sicurezza la traccia dell'antica cavità, anziché dirigere gli sforzi in una direzione errata. Un grosso blocco di roccia, che pastori superstiziosi avevano fatto rotolare un tempo davanti all'ingresso, si trovava completamente messo a nudo; il suo aspetto non era affatto quello di una pietra originatasi dallo scavo.

I miei compagni ed io, cominciammo a ripulire il terreno tutt'attorno alla grossa pietra. E poco dopo, in basso, sulla sinistra, riuscimmo a scoprire il sotterraneo...»

[nel testo originale in lingua francese: «L'année suivante, j'eus l'occasion de faire, en compagnie de quelques amis italiens, entre le 15 et le 18 août 1930, une seconde visite, plus fructueuse, à la grotte de l'Apennin. Notre petite troupe avait quitté Norcia dans la matinéé du 15 août. Le 16, nous nous trouvions dans un campement de bergers, à l'altitude de 1800 mètres. Le 19 [erroné pour le 17 - note du rédacteur] au matin, nous attegnions la grotte, vers le 8 heures. Quelle paix autour de la Sibylle, dans le voisinage du paradis!...

La caverne était sens dessus dessous. De récents travaux d'exploration en avaient complètement modifié l'habitus. Masquèe l'ouverture du souterrain. On distinguait quelques amas de pierres gluantes. Les fouilleurs inexpérimentés, vu la peine qu'ils s'étaient donnée, auraient peut-être réussi à découvrir quelque chose si, au lieu de prendre une mauvaise direction, ils avaient suivi avec plus de confiance le tracé de l'antique terrier. Un gros quartier de roche, que des bergers superstitieux avaient fait rouler autrefois devant l'ouverture, se trouvait complètement mis à nu; son aspect n'était pas celui d'une pierre de rapport.

Mes compagnon et moi, nous commençâmes à déblayer le terreau tout autour de la grosse pierre. Et bientôt, en bas, vers la gauche, nous découvrîmes le souterrain....»]

28 Jun 2017

Confronting the Sibyl: modern technology vs. antique spell

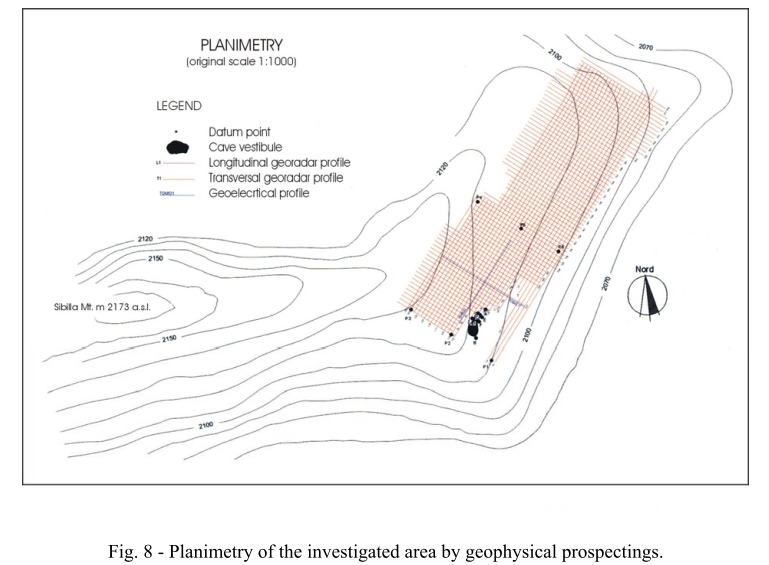

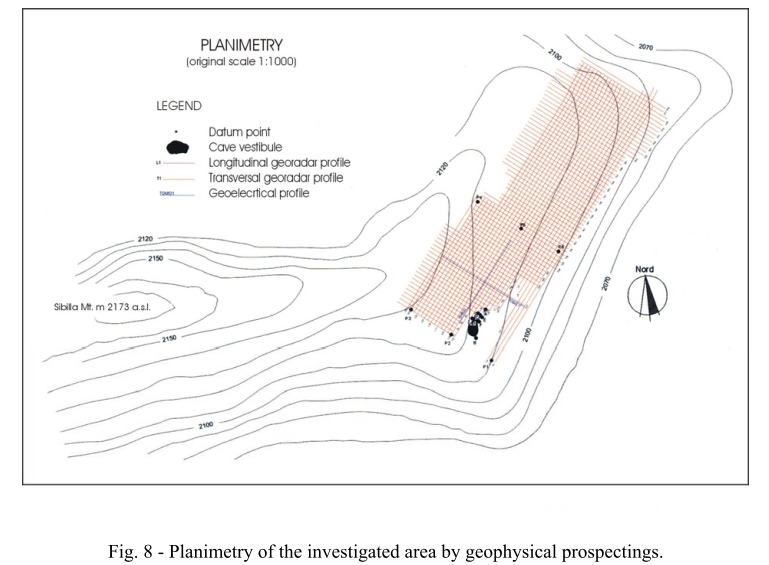

In the fall of 2000, an expedition carrying a bulky machinery ascended the Sibyl's mountain-top. They were determined to challenge the ancient prophetess with the most advanced technology: the georadar analysis.

«The zone is not very large», they wrote, «it is encircled by precipices, and it lies on a very steep slope, which is difficult to reach». They were forced to discard the classical seismic method (disruptive to an excessive degree) and selected the georadar analysis, which offered the additional advantage of an «easy transportation of equipment to the site».

They positioned the device at many spots along a predetermined grid on the cliff of Mount Sibyl (see figure), and shot ground-penetrating microwave radio pulses at the Sibyl's rocky surface. In this way they covered some 9 linear kilometers just around the cave's collapsed entrance.

The results were amazing (see figure). The echoing pulses, as reflected by the subterranean structures, «clearly individuate a fracture in the underground», they reported, «stretching roughly in a direction E-W and emerging southwards». There were «horizontal and vertical hollows, with an average width of about 2 metres (going up to a width of 8 m), located at varying depths of between those of 10 and 14 metres». The horizontal development of the hidden cavities reached «a maximum size of about 300 m, with galleries a few meters in diameter, located at different depths».

Was the Apennine Sibyl about to surrender and deliver all of her secrets? The answer - unfortunately - was no: as the scientists wrote in their paper, published in 2007 by the Geological Society of London, the subsequent investigative phase, which would imply the drilling of probing holes on the mountain-top, «has been unexplainably prohibited by a veto of the Sibillini Mountain National Park Office and of other local institutions».

And the secrets of the Sibyl remain veiled.

(You can read the complete scientific paper by D. Aringoli, B. Gentili, G. Pambianchi and A. M. Piscitelli here)

Affrontando la Sibilla: tecnologia innovativa contro antichissimo incanto

Nell'autunno del 2000, una spedizione che portava con sé un ingombrante macchinario risaliva il Monte Sibilla fino alla cima. Gli esploratori erano determinati a sfidare l'antica profetessa utilizzando la tecnologia più evoluta: il georadar.

«L'area non è molto spaziosa», scrissero poi, «è circondata da precipizi, ed è situata su di un pendio estremamente ripido, raggiungibile solo con difficoltà». Avevano dovuto rinunciare all'utilizzo del classico metodo sismico (eccessivamente distruttivo) e avevano quindi deciso di eseguire una campagna di analisi basata sul georadar, che offriva il vantaggio aggiuntivo di permettere «un più facile trasporto del macchinario in sito».

Posizionarono quindi l'apparato in numerosi punti situati lungo una griglia predeterminata sul picco del Monte Sibilla (vedere figura), lanciando contro la superficie rocciosa della Sibilla potenti impulsi radio a microonde, in grado di penetrare all'interno del suolo. In questo modo, riuscirono a coprire circa 9 chilometri lineari in prossimità dell'ingresso crollato della grotta.

I risultati furono sorprendenti (vedere figura). Gli impulsi riflessi, riverberati dalle sottostanti strutture sotterranee, resero possibile «individuare chiaramente una frattura nel sottosuolo», scrissero, «che si estende grossolanamente in direzione E-W per emergere in direzione sud». Si trattava di «cavità orizzontali e verticali, con un'ampiezza media di circa 2 metri (fino ad una larghezza massima di 8 metri), situati a profondità variabili tra i 10 e i 14 metri». Lo sviluppo orizzontale dei vuoti nascosti raggiungeva «una dimensione massima pari a circa 300 m, con gallerie di alcuni metri di diametro, localizzate a differenti profondità».

Possibile che la Sibilla Appenninica stesse realmente per arrendersi e disvelare tutti i propri segreti? La risposta - sfortunatamente - è negativa: come gli stessi ricercatori scrivono nella relazione scientifica pubblicata nel 2007 a cura della Geological Society di Londra, la successiva fase investigativa, che avrebbe comportato l'esecuzione di fori di assaggio sulla cima della montagna, «fu inaspettatamente resa impossibile da un diniego opposto dall'Ufficio del Parco Nazionale dei Monti Sibillini e da altre istituzioni locali».

E così, i secreti della Sibilla rimangono ancora oggi inviolati.

(Potete leggere qui l'articolo scientifico completo pubblicato da D. Aringoli, B. Gentili, G. Pambianchi e A. M. Piscitelli nel 2007)

27 May 2017

A seventeenth-century poet from Norcia meets the Apennine Sibyl: Giovanni Battista Lalli /2

As we have seen in previous posts, the Apennine Sibyl is closely connected to the Cumaean Sibyl. This peculiar link is highlighted, among others, by Giovanni Battista Lalli, a poet from Norcia who lived in the seventeenth century.

Let's see what he writes in his work "Ruined Jerusalem":

«It is commonly known that she had to depart from Cuma, where the illustrious prophetess had her first abode, as too many visitors used to disrupt her rest: for quietness' sake she then moved to the remote, secluded peaks of the mountains around Norcia. There she hides from the nosy and the rude, and seldom elects to unveil grave secrets to travellers.».

[in the original Italian poetic text:

«È fama che da Cuma, ove le prime

Stanze l'illustre profetessa ottenne,

Mentre colà troppa frequenza opprime

La sua quiete, à lei partir convenne:

Ne le rimote inaccessibil cime

Del Norsin monte, à riposar se'n venne.

Dal curioso volgo ivi si cela,

E raro alti secreti altrui rivela.»]

So, according to an ancient lore, the Apennine Sibyl was the Cumaean oracle who had settled into a new sanctuary amid the lofty ridges of central Apennines to shun the pressure of the populace who begged for prophecies and divinatory responses.

How it happened that the noble prophetess selected this sequestered place near Norcia? Was that by a mere chance? What call has driven the Cumaean Sibyl from her cave near Naples to another cavern on a precipitous peak between Marche and Umbria?

We don't know. But we can imagine that the cavern in the Apennines was not simply another empty cavern. Some other oracle, or deity, was already worshipped there, maybe in an ancient past.

Un poeta nursino del diciassettesimo secolo incontra la Sibilla Appenninica: Giovanni Battista Lalli /2

Come abbiamo visto in post precedenti, la Sibilla Appenninica sembra mostrare una stretta connessione con un'altra Sibilla, la Cumana. Questo peculiare legame è posto in evidenza, tra gli altri, anche da Giovanni Battista Lalli, un poeta nursino vissuto nel diciassettesimo secolo.

Ecco cosa scrive il Lalli nel suo poema "Gerusalemme Desolata":

«È fama che da Cuma, ove le prime

Stanze l'illustre profetessa ottenne,

Mentre colà troppa frequenza opprime

La sua quiete, à lei partir convenne:

Ne le rimote inaccessibil cime

Del Norsin monte, à riposar se'n venne.

Dal curioso volgo ivi si cela,

E raro alti secreti altrui rivela.»

Dunque, secondo un'antica tradizione, la Sibilla Appenninica era proprio l'oracolo di Cuma, il quale era venuto a stabilirsi presso un nuovo rifugio posto tra le elevate cime dell'Appennino centrale, al fine di sfuggire alla pressione di una popolazione ignorante sempre in cerca di profezie e divinazioni.

Ma come è potuto accadere che la nobile profetessa abbia potuto scegliere proprio questi luoghi così remoti, in prossimità della lontana città di Norcia? Fu una mera casualità? Quale richiamo ha sospinto la Sibilla Cumana fuori dal proprio antro napoletano fino ad un'altra caverna situata su di un picco scosceso elevantesi tra le Marche e l'Umbria?

Non possiamo saperlo. Ma possiamo immaginare che la caverna tra gli Appennini non fosse semplicemente una grotta vuota e desolata. Qualche altro oracolo, o forse divinità, era già stato oggetto di venerazione in quel luogo, forse in un passato molto antico.

15 May 2017

A seventeenth-century poet from Norcia meets the Apennine Sibyl: Giovanni Battista Lalli /1

In 1629 Giovanni Battista Lalli, a man of letter originating from Norcia, wrote a poem dedicated to Roman Emperor Titus Vespasian, "Ruined Jerusalem". The Emperor's grand-mother, Vespasia Polla, was born from an aristocratic family whose roots were in ancient Norcia, and Lalli intended to celebrate the fame and deeds of a most illustrious offspring of his own land.

In depicting the ranks of soldiers which were supporting Titus in his successful effort to conquer Jerusalem in 70 A.D., Lalli portrays two generals, Leonzo and Fuscone, who had joined the Roman troops «from ancient Norcia with its snow-clad mountains» (in Italian: «di Norsia antica dal nevoso monte»). Leonzo, an elderly man, tells Titus that when he was young he had accompanied his grand-mother Vespasia to the cave of the Sibyl: she wanted to ask the oracle and learn about the fate and future fortune of his child grand-son, the Emperor-to-be Titus.

And here is the description of the Sibyl's cave, as put down by Lalli, who certainly had the occasion to see the real cavern as it appeared to visitors at the beginning of the seventeenth century:

«After having confronted with much effort, and conquered, the precipitous height of Mount Vettore, she [Vespasia Polla] reached the cavern which in its unfathomable bowels conceals the wise Woman. There opens the gloomy, awful mouth of that huge Sibyl's cave; and neither Sun ever breaks in, nor transparent air, as horrible darkness alone rules there with its eternal night. Made of sheer iron is the heart of those who dare to get through, fearing not in their uncorrupted soul, for the cavern is guarded by Dragons and Panthers, and a hundred formidable Hydras and beasts».

[in the original Italian poetic text:

«E di Vittor già superata, e vinta,

con sudor molto, la scoscesa altezza;

Pervenne à l'antro, che ne le profonde

Viscere sue, la saggia Donna asconde.

S'apre la bocca horribilmente oscura

Di quella immane Sibillina grotta;

Ove il Sol mai non entra, ò l'aria pura;

Ma 'l fosco horror perpetuamente annotta:

Ben hà di ferro il cor chi s'assicura

D'entrarvi, e da timor l'alma incorrotta;

Perch'in guardia di lei, Draghi e Pantere

Stanno, e cento Idre spaventose, e fere»]

Lalli's words are truly trhilling and full of emotional feeling: they are to be considered as a true description of the cave's appearance in the early seventeenth century. Lalli actually saw the cave's entrance, and the vision deeply impressed upon his soul.

At that time, the cave was dark and cold and deep and frightful: a sight that was not easily forgotten, and a further good reason for the cavern's sinister renown among travellers coming from all over Europe.

Un poeta nursino del diciassettesimo secolo incontra la Sibilla Appenninica: Giovanni Battista Lalli /1

Nel 1629 Giovanni Battista Lalli, studioso e letterato originario di Norcia, pubblicò un poema dedicato all'imperatore romano Tito, "Gerusalemme Disolata". La nonna dell'imperatore, Vespasia Polla, era nata all'interno di una famiglia aristocratica che aveva le proprie radici nella Norcia antica, e l'intento di Lalli era quello di rendere onore alla fama e alle gesta di uno dei figli più illustri della sua terra.

Nel descrivere le schiere di soldati che sostenevano Tito nella sua campagna vittoriosa per la conquista di Gerusalemme nel 70 d.C., Lalli ci presenta due generali, Leonzo e Fuscone, che si erano uniti alle legioni romane come contingente proveniente «di Norsia antica dal nevoso monte». Leonzo, uomo ormai anziano, racconta a Tito di come, all'epoca della propria giovinezza, egli avesse accompagnato la madre di suo padre, Vespasia, fino alla grotta della Sibilla: ella voleva interrogare l'oracolo per conoscere i destini e la futura fortuna del proprio nipote ancora bambino, il futuro imperatore Tito.

Ed ecco la descrizione della caverna della Sibilla, così come riportata nel proprio poema dal Lalli, il quale aveva certamente avuto l'opportunità di vedere la grotta così come essa appariva ai visitatori all'inizio del diciassettesimo secolo:

«E di Vittor già superata, e vinta,

con sudor molto, la scoscesa altezza;

Pervenne à l'antro, che ne le profonde

Viscere sue, la saggia Donna asconde.

S'apre la bocca horribilmente oscura

Di quella immane Sibillina grotta;

Ove il Sol mai non entra, ò l'aria pura;

Ma 'l fosco horror perpetuamente annotta:

Ben hà di ferro il cor chi s'assicura

D'entrarvi, e da timor l'alma incorrotta;

Perch'in guardia di lei, Draghi e Pantere

Stanno, e cento Idre spaventose, e fere»

Le parole del Lalli sono particolarmente evocative, e sembrano essere ricolme di profonda e sincera emozione: si tratta di una descrizione particolarmente veritiera di come doveva apparire quella grotta all'inizio del diciassettesimo secolo. Il Lalli deve avere effettivamente osservato, con i propri occhi, l'ingresso della caverna, riportandone un'impressione forte e particolarmente vivida.

A quel tempo, la grotta era oscura, e fredda, e profonda, e terrificante: una visione che di certo non poteva essere dimenticata facilmente, e una ragione in più in grado di spiegare la fama sinistra della quale la caverna godeva tra i viaggiatori provenienti da ogni parte d'Europa.

5 Mar 2017

The Apennine Sibyl under Fascist rule in Italy: Giuseppe Moretti

Italians have never attained the degree of wicked folly reached by German Nazis, who were utterly and morbidly fascinated by the occult and the esoteric; nevertheless, the captivating power of the Apennine Sibyl's legend was so strong that it appears to have bewitched - though for far more positive scientific and cultural reasons - a prominent member of the Italian Fascist administration in 1920s: Giuseppe Moretti.

Moretti was a gifted, professional archeologist who was bestowed the highest honours during the Fascist rule in Italy, as he was appointed the Director General at the Department of Antiquities and Heritage of Latium and head of the National Roman Museum. In 1937, he was entrusted the difficult task to carry out the complex excavations in central Rome during which the most valuable fragments of Augustus' Ara Pacis (see picture) were unearthed, restored and positioned in a different location along the Tiber's bank, where we can still see them in present days.

Before taking his high post in Rome, Moretti had been the head of the Department of Antiquities in the local areas of Marche and Abruzzi. In addition to that, he was born in the Marche region: he had lived his childhood in San Severino Marche - at the very door of the Sibillini Mountain Range - he knew the Sibyl's legend at heart, and his soul could not avoid the centuries-old spell that trickled out from the gloomy cave opening on the mountain-top.

So in 1926, when Italian Senator Pio Rajna - the philologist who was equally fascinated by the same ancient legend - proposed to him a new excavation campaign at the cave, he had no hesitation: picks and spades were carried up to the cliff of Mount Sibyl once more (see picture), this time under public administration control. Results came in very quickly: preliminary probing proved that an underground hollow was actually present, and the explorers were able to creep into it «through a narrow crack which is to be found within the slanting layers of rock». However, the subterranean cavity was «less than twenty-five feet long, thirteen feet wide and ten feet high», with no further access «to any internal vaults, galleries or pits. This vestibule alone presents itself free from the rubble».

The hidden magic was at work again, as in past centuries: men were on the mountain-top, as contemporary knights, in search of the hidden realm of the Sibyl. But the prophetess wouldn't let her secret be uncovered easily. And Giuseppe Moretti, a passionate, skilled scientist couldn't do more than write the following lines in his official campaigning report: «a small opening only, from that same vestibule, betokens the possible existence, in a long-gone past or maybe even in present times, not really of the actual chambers that popular lore had turned into the Queen Sibyl's paradise, but at least of further hollows that might be placed beyond the entrance cavity».

The dream could not be brought into the real world. The cave still resisted any efforts to break in. Queen Sibyl was still concealed under layers and layers of rock. But the heart of men had made a further attempt at unveiling the mystery: a trail of endeavours that is rooted into antique past and still continues today.

La Sibilla Appenninica nel periodo del Fascismo: Giuseppe Moretti

Gli italiani non hanno mai raggiunto il livello di malvagia follìa al quale sono pervenuti i Nazisti, con la loro malsana fascinazione per l'occultismo e l'esoterismo; nondimeno, il potere di attrazione della leggenda della Sibilla Appenninica è risultato essere così potente da ammaliare, seppure per ben più positive motivazioni scientifiche e culturali, anche un elemento importante dell'amministrazione dell'Italia Fascista, negli anni '20 dello scorso secolo: Giuseppe Moretti.

Moretti è stato un archeologo professionale e dotato di grande talento, il quale ha ricoperto incarichi istituzionali di elevatissimo livello durante il regime fascista: fu infatti nominato Soprintendente alle Antichità del Lazio e direttore del Museo Nazionale Romano. Nel 1937, gli fu affidato il difficile compito di condurre le complesse attività di scavo, nel centro storico di Roma, per il recupero dei frammenti dell'Ara Pacis di Augusto (cfr. immagine), il loro restauro ed il riposizionamento in un sito diverso lungo le rive del Tevere, dove è possibile ammirarli ancor oggi.

Prima di assumere il prestigioso incarico romano, Moretti era stato a capo della Soprintendenza alle Antichità delle Marche e degli Abruzzi. Oltre a ciò, egli era anche originario delle Marche: aveva vissuto la propria infanzia a San Severino Marche - alle porte del massiccio dei Monti Sibillini - conosceva dettagliatamente la favola della Sibilla, cosicché il suo animo non poteva evitare di subire l'influsso antico che fuoriusciva da quella caverna tenebrosa che si apriva sulla cima della montagna.

Così, nel 1926, quando il Senatore Pio Rajna - il filologo che era parimenti affascinato dalla medesima leggenda - sottopose alla sua attenzione la possibilità di effettuare una nuova campagna di scavo, egli non esitò: pale e picconi vennero trasportati di nuovo sulla cima del Monte Sibilla (cfr. figura), questa volta sotto il controllo della Soprintendenza. I risultati giunsero in fretta: i sondaggi preliminari dimostrarono che una cavità sotterranea era effettivamente esistente, essendo accessibile «attraverso una singolare fenditura aperta tra i filoni obliqui di roccia». Essa, però, «non ha più di otto metri di lunghezza,quattro di larghezza e tre metri di altezza», non evidenziando inoltre alcun accesso «alle sale o agli ambulacri o alle voragini interne. Vuoto è rimasto solo il vestibolo».

La magia nascosta era di nuovo all'opera, come nei secoli già trascorsi: degli uomini si trovavano sulla cima della montagna, come moderni cavalieri, in cerca del regno segreto della Sibilla. Ma la profetessa non avrebbe lasciato che il suo segreto fosse svelato così facilmente. E Giuseppe Moretti, scienziato appassionato e di esperienza, non poté fare altro che scrivere le seguenti frasi nel proprio rapporto relativo alla campagna di scavo: «solo un foro lascia supporre che siano esistite e ancora esistano, se non le aule che la leggenda aveva mutate in paradiso della Regina Sibilla, almeno altre cavità a cui la presente sia di vestibolo».

Il sogno non poté essere portato alla luce del mondo reale. La grotta resisteva ancora ad ogni tentativo di penetrare al suo interno. La Regina Sibilla era ancora occultata sotto immani spessori di roccia. Ma il cuore dell'uomo aveva effettuato un ulteriore tentativo di svelare il mistero: una catena di ricerche che è radicata nel più antico passato e che continua ancora oggi.

8 Feb 2017

Digging the cave under the ardent radiance of the summer sun

August, 1920: the excavations proceed tirelessly on the Sibyl's crowned mountain-top. The men work with enthusiasm at the cave's entrance by the pick and shovel, in hopes of breaking into the inner recesses of the cavern.

At the time, the gaping mouth of the cave was still visible: a dark hollow under the ruthless sunlight which flooded the cliff at midday, a condition almost unbearable for the people who were engaged in the daring expedition.

And yet, only a few years later - when the Committee would gain the support of important members of the Italian Fascist party for a new round of excavations - the entrance to the cave will prove to have vanished once more amid the rubble and broken stones: unknown treasure hunters had attempted unsuccessfully at breaking into the cave, causing additional destruction and damaging the outer hollow irreparably.

Gli scavi alla caverna sotto l'ardente sole estivo

Agosto 1920: sulla cima coronata del Monte Sibilla gli scavi procedono alacremente. Presso l'ingresso della caverna, gli uomini lavorano di pala e di piccone con grande entusiasmo, nella speranza di riuscire a penetrare nei recessi più nascosti della grotta.

A quel tempo, l'imbocco tenebroso della grotta era ancora visibile: una cavità buia sotto l'impietosa luce solare che inondava la vetta a mezzogiorno, una condizione quasi insopportabile per gli uomini impegnati in quella rischiosa spedizione.

Ma, pochissimi anni dopo - quando il Comitato avrebbe ottenuto il supporto di membri importanti del Partito fascista per una nuova tornata di scavi – l'ingresso della caverna sarebbe di nuovo sparito tra i detriti e le rocce spezzate: ignoti cercatori di tesori avevano infatti tentato, senza successo, di accedere alla grotta, causando ulteriore distruzione e danneggiando irreparabilmente la porzione esterna della cavità.

5 Feb 2017

Excavating the Sibyl's cave

Why the cave on the Sibyl's mountain-top has never been excavated?

Actually it was.

The first in a series of modern excavation campaigns began in 1920, following a wave of fresh attention for the cavern due to an increasing scrutiny of the legend's roots and historical links carried out by a number of scientists and philologists.

A special committee was set up in Montemonaco, a small hamlet sitting just below the Sibyl's cliff: a «Committee for the excavation of Mount Sibyl's cavern» promoted by Mario Monti Guarnieri.

The excavations were effected in August, supported by good weather and clear sky. And the initial results were absolutely encouraging: indeed, a section of the cave's entrance was unearthed, «shallow and a few yards long, an uncomfortable passageway to be accessed by twisting one's body inside it. A recess of the cave goes markedly down and it seems it might be the initial portion of a passageway sloping down like a staircase towards a further hollow, with the first cave being a sort of anteroom to that subsequent cavity. Yet the latter is presently filled up with stones, both small and large».

And that was just the beginning.

Scavando nella grotta della Sibilla

Perché la grotta posta sulla cima del Monte Sibilla non è stata mai oggetto di tentativi di scavo?

In realtà, ciò ha avuto luogo più volte.

La prima di una serie di moderne campagne di scavo ebbe luogo nell'anno 1920, a seguito di un'ondata di rinnovato interesse per la caverna causato dalla crescente attività di ricerca sulla leggenda, le sue origini e le sue connessioni storiche effettuata da numerosi scienziati e filologi.

Fu dunque creato un comitato a Montemonaco, il piccolo villaggio posto proprio al di sotto della cima della Sibilla: si trattava del “Comitato per gli scavi nella grotta del Monte Sibilla”, promosso da Mario Monti Guarnieri. Gli scavi cominciarono nel mese di agosto, al fine di trarre vantaggio dal bel tempo e dal cielo privo di nubi. I risultati iniziali furono assolutamente promettenti: fu infatti liberata dalla terra una sezione dell'ingresso alla grotta, «una bassa caverna di qualche metro, ove male e curvi si accede. Un angolo della caverna discende sensibilmente verso il basso e sembra esser l’inizio di una galleria discendente a mò di scala per dar adito ad una susseguente grotta, di cui l’attuale caverna non sarebbe che il vestibolo. Ma essa è stata riempita con grosse e piccole pietre».

E questo era solo l'inizio.

29 Jan 2017

The Sibyl's cave, today

The Sibyl's cave rests at the bottom of a shallow hollow, lying on the versant looking towards the south side of the peak. The grassy ground, departing from its usual, barren roughness, gives way to a sort of trench, excavated by all appearances in the very rock of the cliff; it is full of rubble and large broken stones, definitely the offspring of the shattering of the same rocky material of which the mount itself is made. Scaffolding tubes cover with rust, portions of wooden beams, fragments of rotten planks still emerge from the jumble of beaten and disfigured boulders, attesting by their miserable wretchedness to the unsuccessful, devastating attempts at breaking into the cavern by force.

Thus, this is what remains today of the famous cave of the Sibyl.

La grotta della Sibilla, oggi

La grotta della Sibilla è adagiata all’interno di un modesto avvallamento, sul fianco del costone rivolto verso il lato meridionale della rupe. Il suolo erboso, interrompendo la propria rarefatta irregolarità, lascia spazio ad una sorta di scavo, evidentemente eseguito nella roccia viva della vetta, ricolmo di detriti e di macigni frantumati, frutto dello sgretolamento della stessa pietra, della stessa matrice che costituiva la mole della montagna. Tubi di metallo arrugginito, frammenti di travi in legno, resti di assi marcite emergono ancora da quel coacervo di massi percossi, violentati, testimoni ormai decrepiti dei tentativi, infruttuosi e devastanti, di penetrare con la forza all’interno della caverna.

Questo, dunque, è ciò che resta, oggi, della famosa grotta della Sibilla.

15 Jun 2016

The cavern at the end of the nineteenth century

In modern times, the Sibyl's cave could be seen by visitors as a sealed hollow, sitting on its deserted mountain-top. In 1885, Giovambattista Miliani, a member of the family who founded an historical paper factory in Fabriano, on the eastern side of the Apennines, and himself an enthusiastic hiker, pushed himself up to the top of Mount Sibyl, having been lured there, as many others in earlier times, by the enthralling call raised by the ancient legend.

What he found up there was a mere «heap of wrecked stones». No trace of the cave's entrance was to be seen. The access to the Sibyl's kingdom was permanently sealed, buried forever under a solid mound of rocks.

La caverna alla fine del diciannovesimo secolo

In tempi più recenti, la Grotta della Sibilla è apparsa ai visitatori come una cavità occlusa, posta sulla cima deserta di una montagna. Nel 1885, Giovambattista Miliani, un membro della famiglia che avrebbe fondato le storiche Cartiere di Fabriano, appassionato escursionista, si spinse fin sulla cima del Monte Sibilla, attratto, come molti altri in passato, dal misterioso richiamo che si innalzava dall'antica leggenda.

Ciò che egli trovò sulla vetta fu “un cumulo di pietre rimosse”. Nessuna traccia dell'imbocco della caverna era più visibile. L'accesso al regno della Sibilla era definitivamente chiuso, sepolto per sempre sotto una solida montagna di roccia.

1 Jun 2016

The cave sealed

Today the cave on the Sibyl's mountain-top is not accessible anymore. Yet for centuries its fame had run across Europe, so much so that scores of undesired travellers used to flock to Italy from Germany and other northern European countries to visit the cavern. They were not mere tourists. They were wizards and sorcerers coming from their respective homelands to consecrate their spellbooks and "to stage their abominable rituals", as reported in 1650 by Father Fortunato Ciucci, a local scholar and historian.

The town of Norcia, under whose rule the cavern rested at that time, "was then compelled to seal the entrance to the alleged Sibyl, as it is still sealed today". All that occurred in the seventeenth century, but the attempts at breaking into the cavern and meet the fabulous Sibyl weren't over at all.

La grotta sigillata

Oggi la grotta posta sulla cima del Monte Sibilla non è più accessibile. Eppure per molti secoli la sua fama era corsa per l'Europa, tanto che moltitudini di viaggiatori indesiderati erano solite recarsi dalla Germania e da altri Paesi nordeuropei in questi luoghi proprio per visitare la caverna. Non si trattava di semplici turisti. Essi erano anche maghi ed esoteristi, i quali si spingevano fino a queste montagne per consacrare i propri libri magici e per mettere “in opra l'esecranda dottrina”, come testimoniato nel 1650 da Padre Fortunato Ciucci, un erudito locale.

La città di Norcia, che all'epoca controllava il territorio dove si trovava la grotta, “fu forzata […] chiudere l’entrata alla falsa Sibilla come oggidì si trova”. Tutto ciò accadeva nel diciassettesimo secolo, ma i tentativi di penetrare nella caverna ed incontrare la favolosa Sibilla non terminarono certo con il volgere di quel secolo.

28 May 2016

Flight to the Sibyl's cave

What is the appearence of the Sibyl's cave today? Let's fly over the Sibillini Mountains, rush ourselves across the grim crests of Mount Vettore, heading north beyond the sinister Lakes of Pilatus; let's follow the call of the legendary tale up to the very peak of Mount Sibyl, then land on the mountain-top, on the slope looking south.

There we are: now look at the remnants of the famed cavern, a heap of collapsed rocks, rusted scaffolding tubes, and rotten planks. What happened to the cave?

Who ravaged the place, when and why? What were they looking for? The story of the Sibyl's cave is more fascinating than ever.

In volo verso la grotta della Sibilla

Qual è l'aspetto della Grotta della Sibilla oggi? Proviamo a volare al di sopra del massiccio dei Monti Sibillini, precipitiamoci attraverso le paurose creste del Monte Vettore, dirigendoci a nord verso i sinistri Laghi di Pilato; seguiamo il richiamo del leggendario racconto fino alla cima del picco della Sibilla, e infine atterriamo sulla vetta della montagna, sul pendio che guarda verso sud.

Ecco, siamo qui: ora osserviamo i resti della famosa caverna, un mucchio di pietre crollate, impalcature arrugginite e assi marcite.

Cosa è accaduto a quella grotta? Chi ha ridotto l'ingresso in questo stato? Cosa stavano cercando? La storia della Sibilla sembra essere sempre più affascinante.

27 May 2016

The dark cavern

What was to be found in the Sibyl's cave in Roman times?After climbing the steep mountain-slope, the visitor would reach the Sibyl's peak, an isolated place of worship situated at an elevation of more than 7,000 feet. Nothing but a frosty wind and the remote stars above would accompany the believer. There, the dark cave, with carved lintels and pillars, would be waiting for men to enter its recesses. Inside the cave, no one can tell what was to be encountered: an altar, a ritual fire, a prophesying oracle. A Sibyl, like the one of Delphi, in Greece: «Sibyl», Plutarch wrote in his De Pythiae Oraculis, «who speaks mournful words with delirious lips».

La caverna oscura

Cosa c'era sul Monte della Sibilla in età romana? Dopo avere risalito il ripidio pendio montano, il visitatore avrebbe raggiunto il picco della Sibilla, un sito cultuale totalmente isolato posto ad un'altezza di più di duemila metri. Nulla avrebbe accompagnato il credente se non il vento gelido e le stelle lontane nel cielo. Lassù la caverna buia, tra i pilastri e gli architravi intagliati nella roccia, avrebbe atteso che i visitatori si spingessero al suo interno. Nella grotta, nessuno oggi può dire cosa attendesse quegli uomini: un altare, un fuoco rituale, un oracolo, delle profezie. Forse una Sibilla, come quella di Delfi, in Grecia: «Sibilla», scrive Plutarco nell'opera 'De Pythiae Oraculis', «che pronuncia con bocca folle parole senza riso».

25 May 2016

The cave in Roman times

In present days no one can tell what the Sibyl's cave looked like in antiquity. For certain, on the peak of Mount Sibyl a cavern opened its gloomy jaws providing an access to the mount's internal bowels. Was that a special worship place dedicated to some ancient mother-god? Researchers think it might have been a rocky temple, with carved columns and inscriptions bearing mention of goddess Cybele, but no evidence has ever been found. We can just dream and imagine how it might have appeared to a worshipper coming uphill from the ravines below, in Roman times.

La grotta al tempo dei Romani

Oggi nessuno può essere in grado di dire quale aspetto potesse avere la caverna della Sibilla nell'antichità. Di certo, sulla cima del Monte Sibilla c'era una grotta, che forniva un accesso alle viscere della montagna attraverso le sue fauci oscure. Si trattava forse di uno speciale luogo di culto dedicato a qualche antica divinità-madre? Alcuni pensano che sul posto potesse sorgere un tempio rupestre, con colonne lavorate e iscrizioni legate al nome della dea Cibele, ma nessuna evidenza è mai stata trovata che potesse confermare queste ipotesi. Possiamo dunque solo sognare, e provare ad immaginare come il sito sarebbe potuto apparire ad un orante che si fosse trovato ad ascendere il fianco del monte, in età romana.

7 Nov 2015

How to get to the Sibyl's cliff

Today's tourists can still experience the shiver of an excursion to Mount Sibyl and its historical cave, leaving somewhat behind everyday's life and troubles, and setting off to a journey into myth and legend.

The most impressive way to get to Mount Sibyl is to take the path that leaves the small hamlet of Castelluccio di Norcia, sitting on its hillock which provides an astonishing view on the Great Plains. The trail winds its way up across the sides of Mount Vettore, whose impending vision is both breathtaking and frightening; then it ascends with increased decision to the high ridges of Mount Palazzo Borghese and Mount Porche, a place of sheer beauty where no leaving soul is to be found and the potency of wind and sun rules among the crests. You are already in the realm of the Sibyl, and feel that you have to speak in a low tone, not to disturb the fairies which are part of her hidden retinue.

A long walk along the crest lines then follows: in the airy distance, Mount Sibyl's peak awaits you. This will be an encounter you will never forget.

Come raggiungere il picco della Sibilla

Oggi i turisti possono ancora provare il brivido di un'escursione al Monte Sibilla e alla sua storica grotta, lasciando dietro di sé la vita e le preoccupazioni di tutti i giorni e lanciandosi in un viaggio all'interno del mito e della leggenda.

La via più impressionante per giungere al Monte Sibilla è quella che parte da Castelluccio di Norcia, il villaggio posto sull'elevazione che sovrasta il fantastico panorama del Pian Grande. Il sentiero si arrampica accanto alle pendici del Monte Vettore, la cui visione incombente è allo stesso tempo mozzafiato e terribile; la pista prosegue poi in quota con decisione fino alle selle del Palazzo Borghese e di Monte Porche, un luogo di straordinaria bellezza e totalmente isolato dal mondo, dove solamente il vento e la luce solare dominano le alte creste. Vi trovate già, a questo punto, nel regno della Sibilla: sentirete la necessità di parlare a bassa voce, per non disturbare gli esseri soprannaturali che fanno parte del suo magico seguito.

Seguirà infine una lunga camminata lungo le linee di cresta: nella distanza azzurrina, il Monte Sibilla vi starà aspettando. E sarà un incontro che non dimenticherete mai.