2 Jan 2020

Pontius Pilate and the shape of the waters /23. The legend lives on

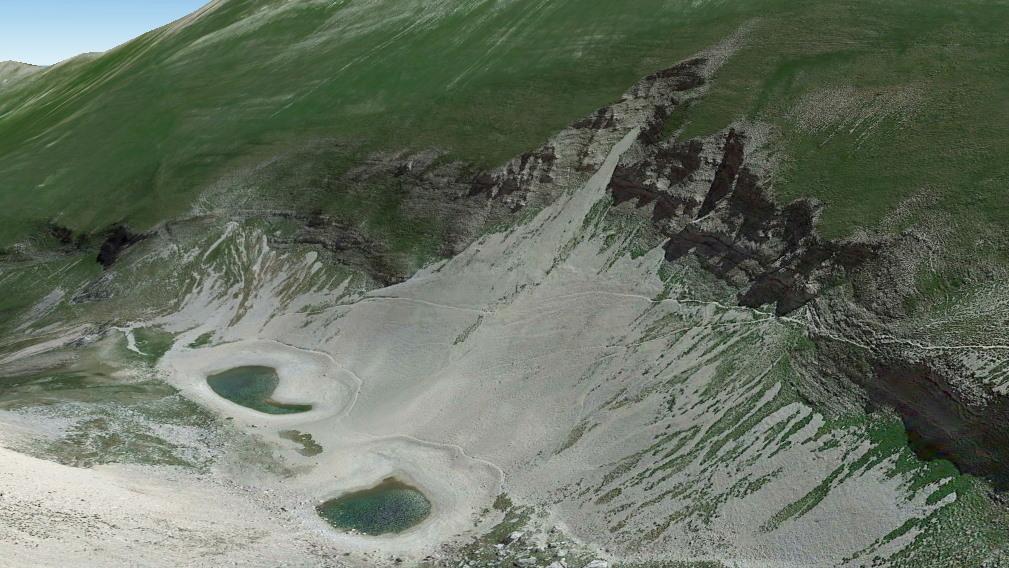

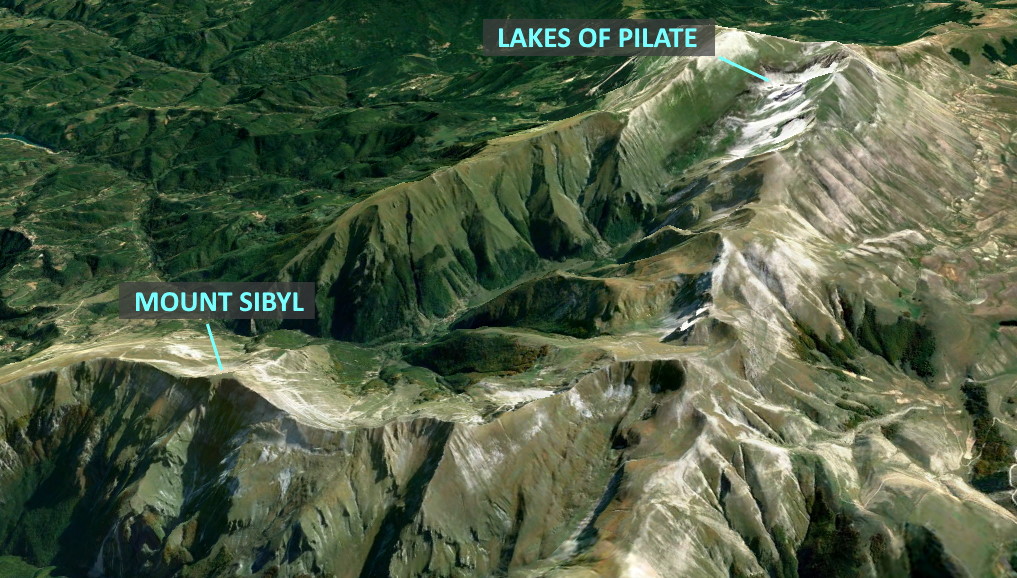

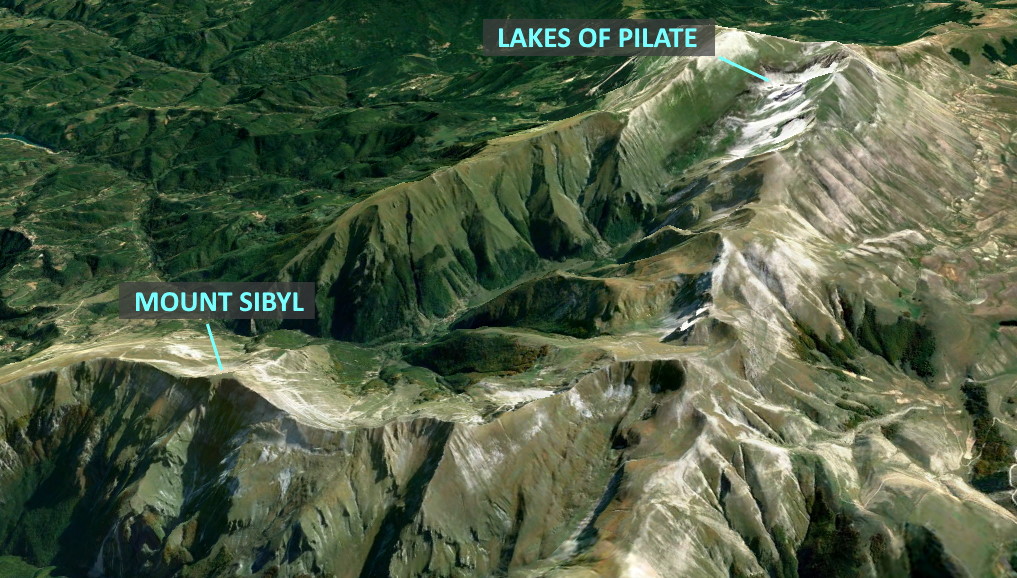

Pontius Pilate and the Sibillini Mountain Range, in the Italian Apennines. A necromantic Lake entitled to the first-century Roman prefect who sentenced Jesus Christ to death. A basin of dark waters encircled by the precipitous ravines of Mount Vettore: a sinister, solitary nest that once housed a glacier set in the Sibillini Mountain Range, and vanished thousands of years ago.

In the present research paper, we have been riding through the centuries, in search of the shape of the Lake of Pilate: one Lake, two Lakes, and, finally, no Lake at all.

A long journey that has taken us from the sinister Lake of past centuries down to the scant, depleted Lakes of our present times, and their anticipated, imminent death in a future that is as close as global climate change.

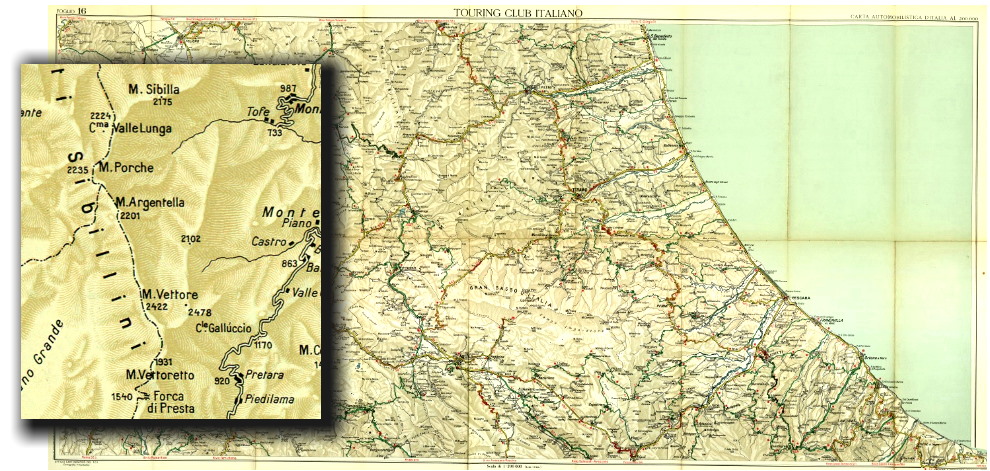

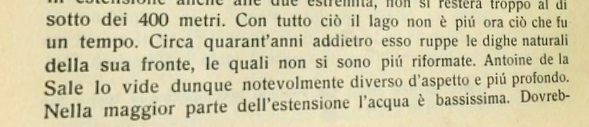

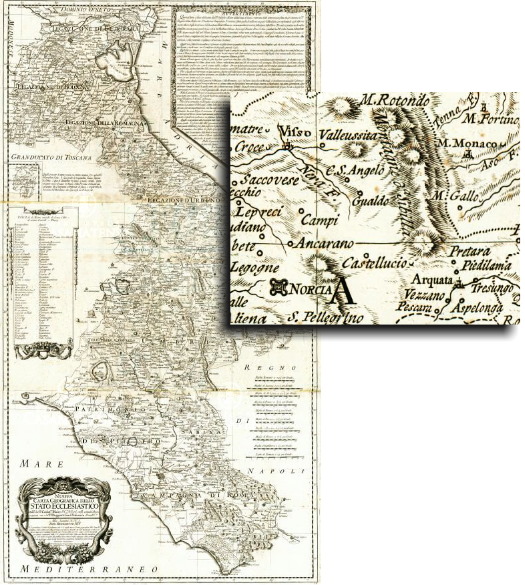

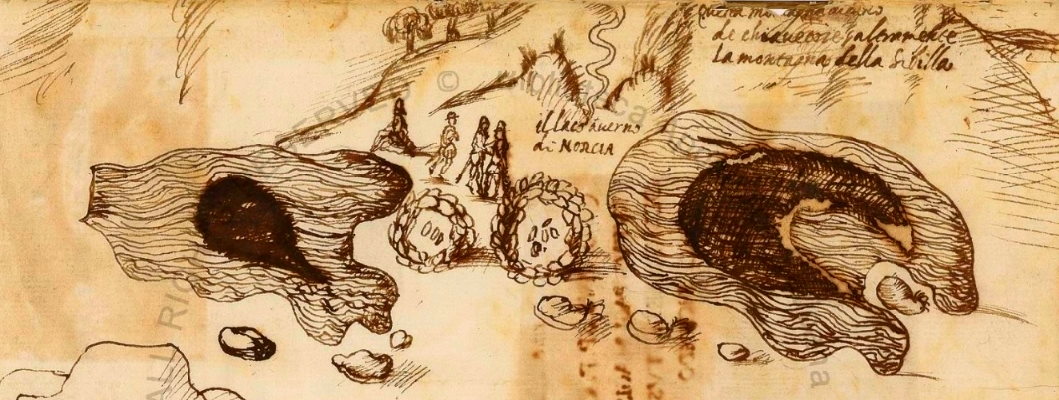

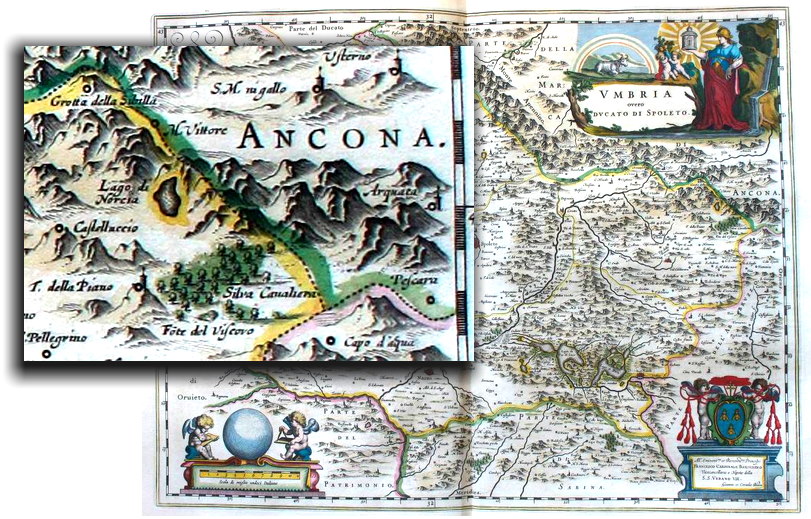

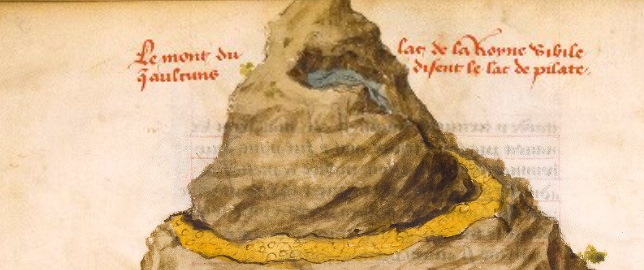

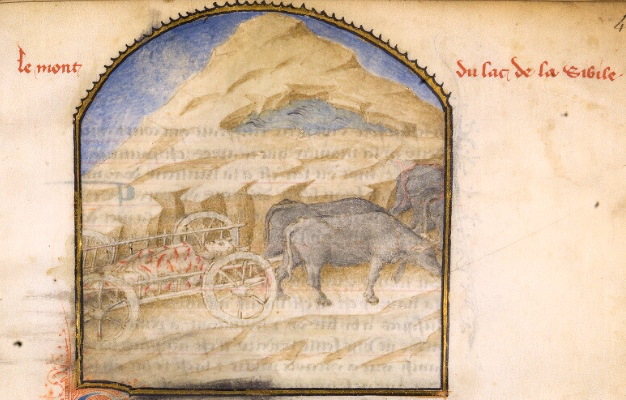

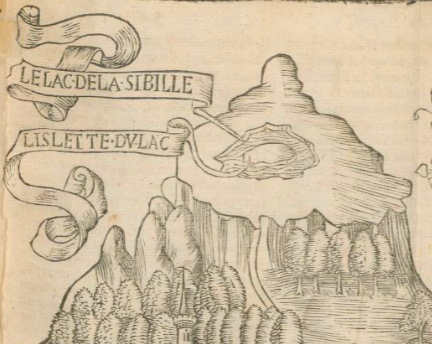

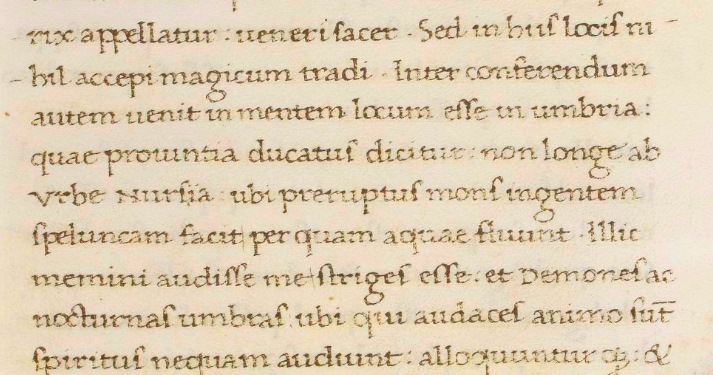

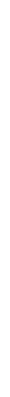

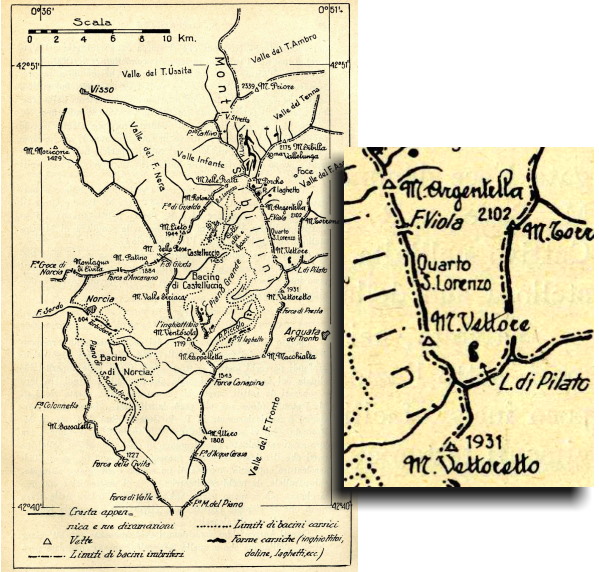

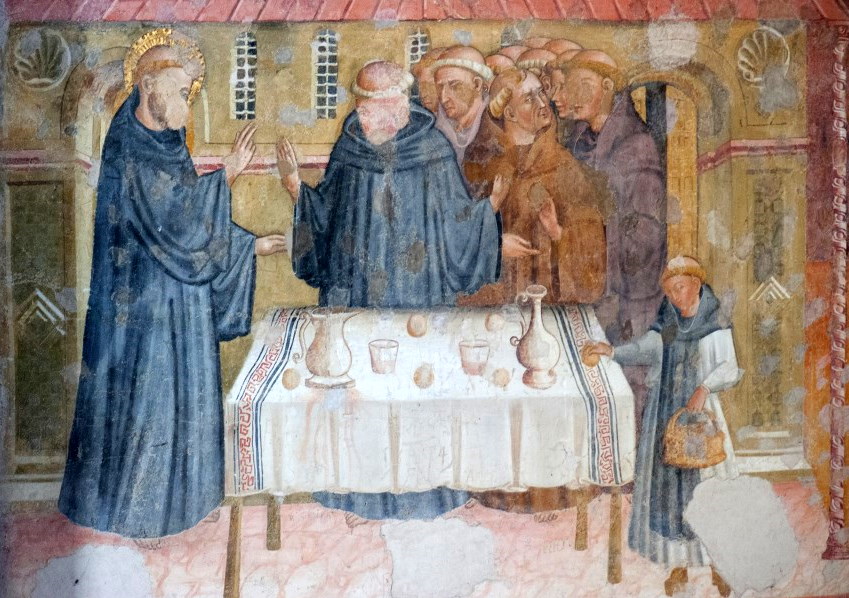

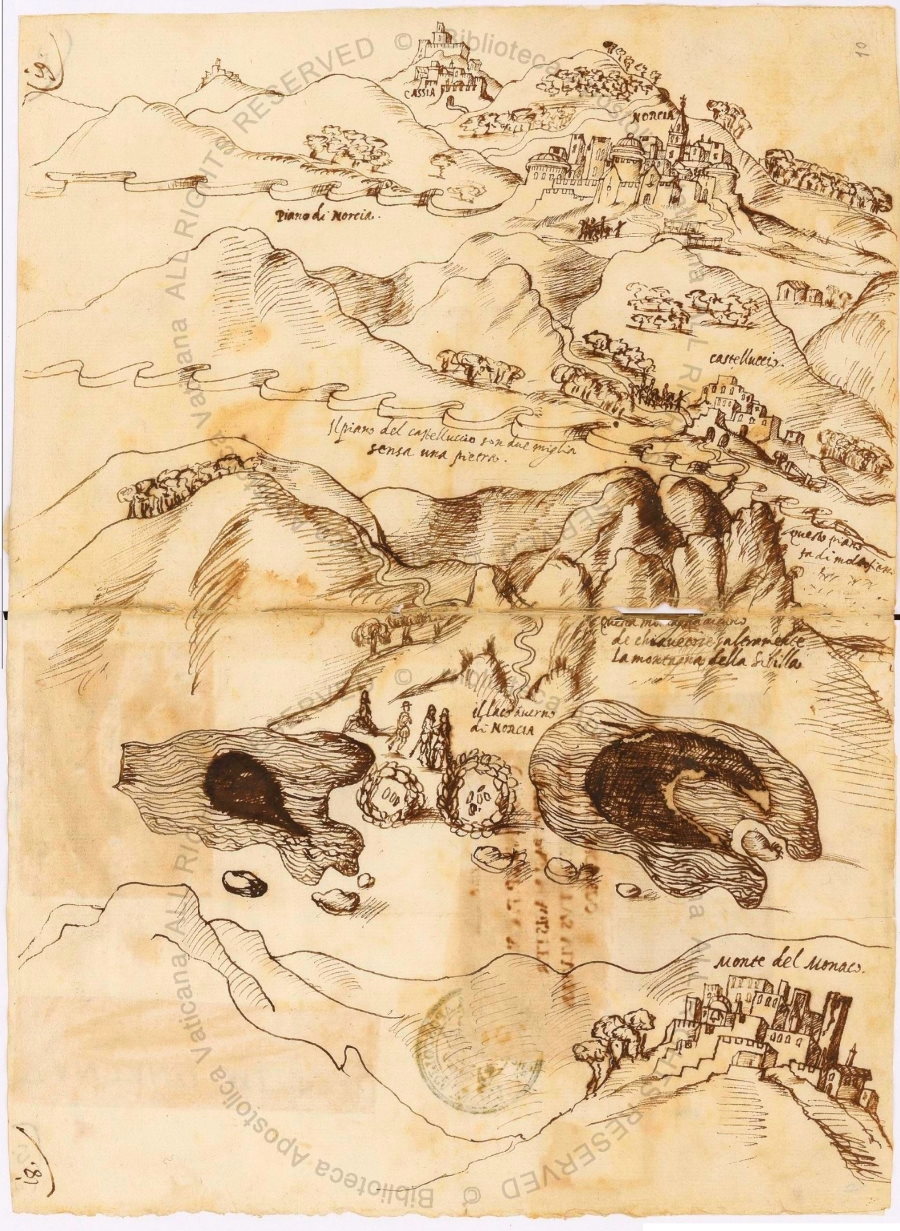

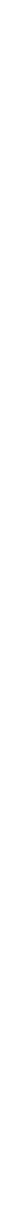

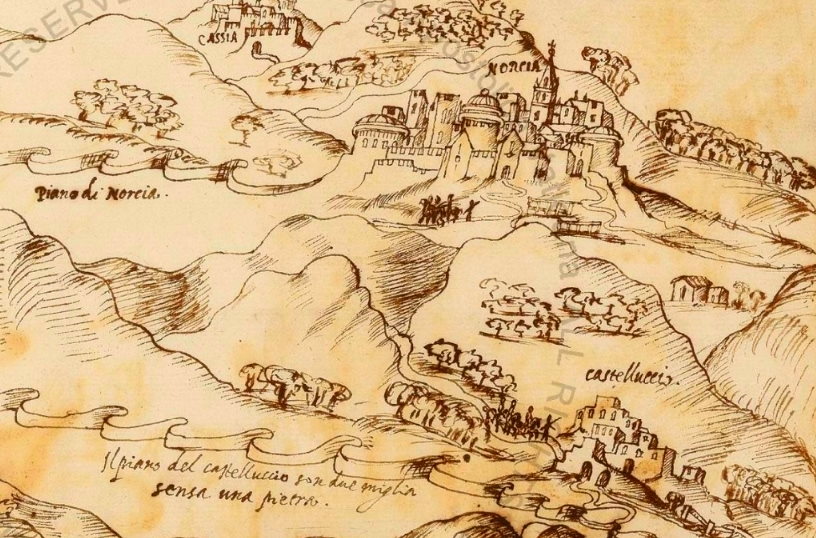

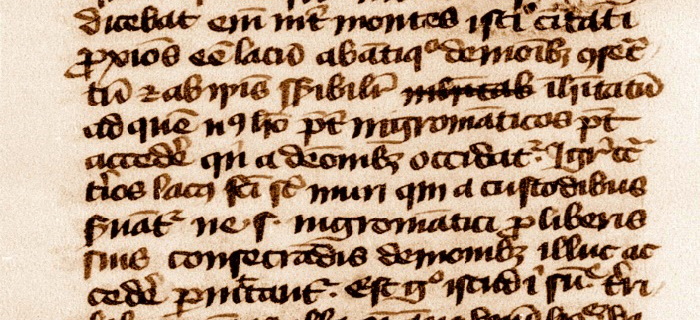

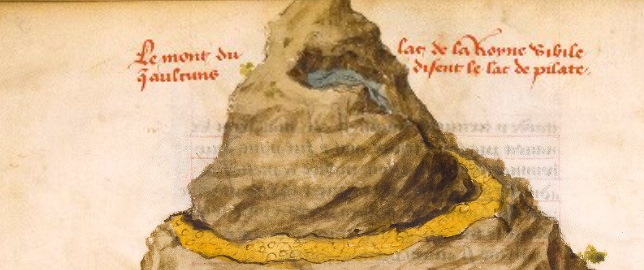

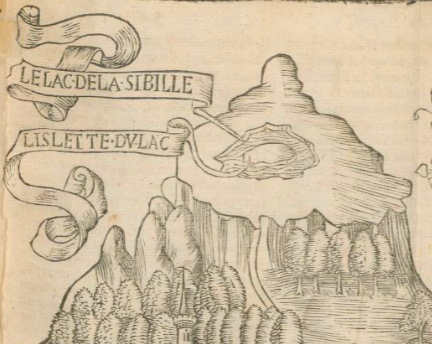

We started our travel from the fourteenth century, with Petrus Berchorius and his emotional words: «amid the peaks which raise near that town [Norcia] there is a lake, which from antique times is sacred to demons and conspicuously inhabited by them...». Then, we joined French gentleman Antoine de la Sale in his 1420 visit to the Lake, named after Pilate and the Sibyl (Fig. 1). From then on, descriptions and references of an ominous Lake sitting amid the mountains of the Sibyl, in central Italy, begin to follow one after another, across the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth century.

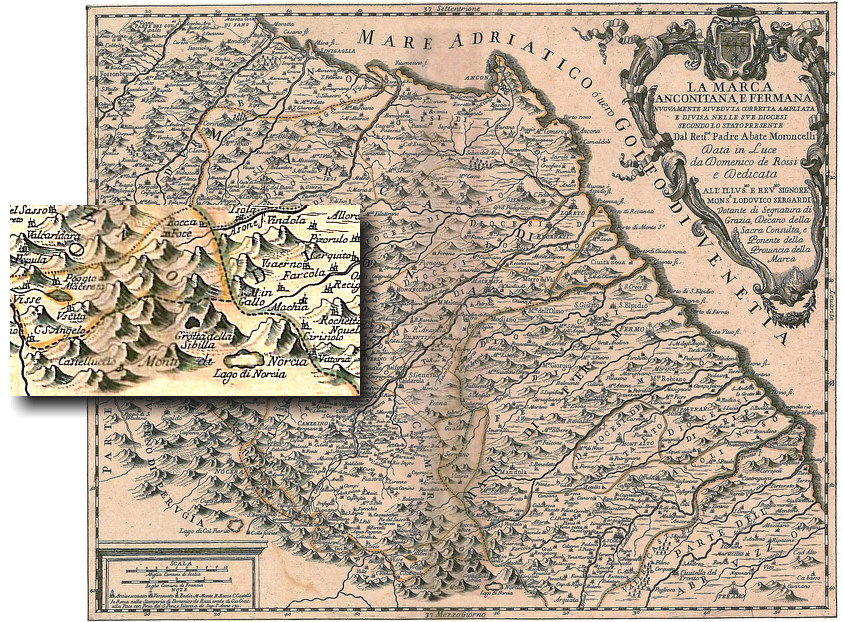

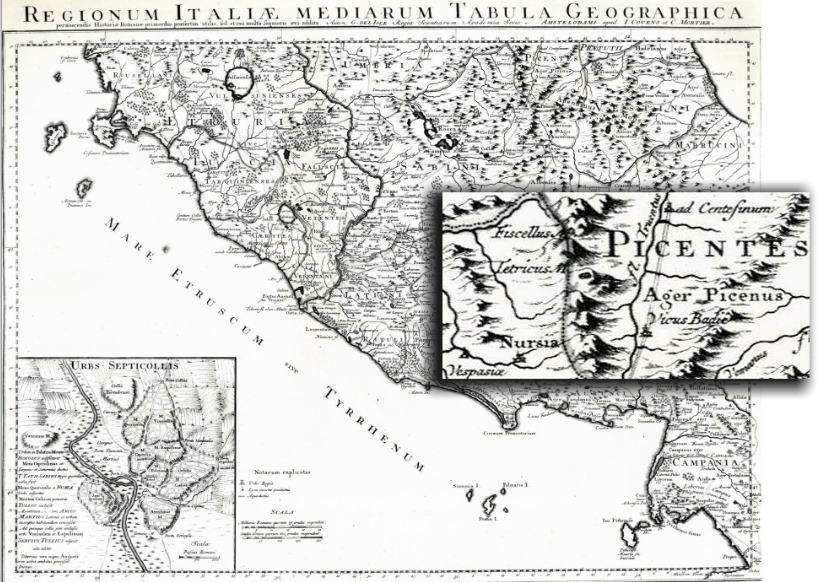

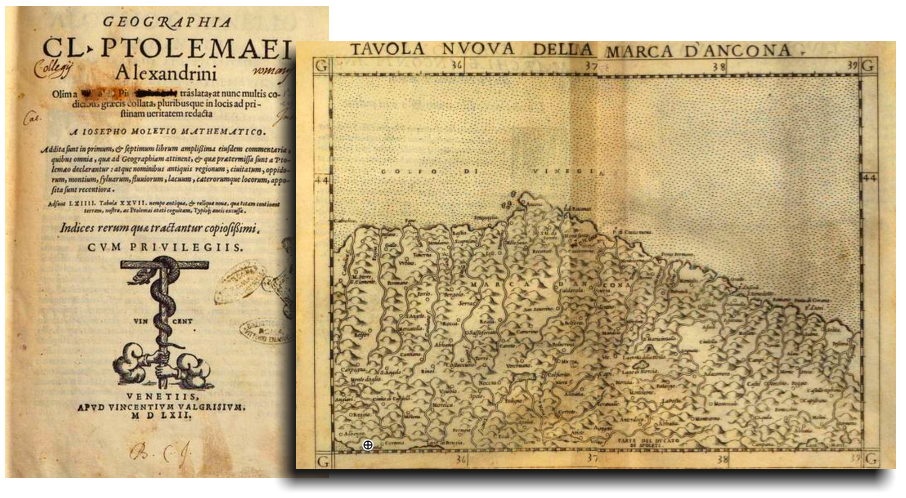

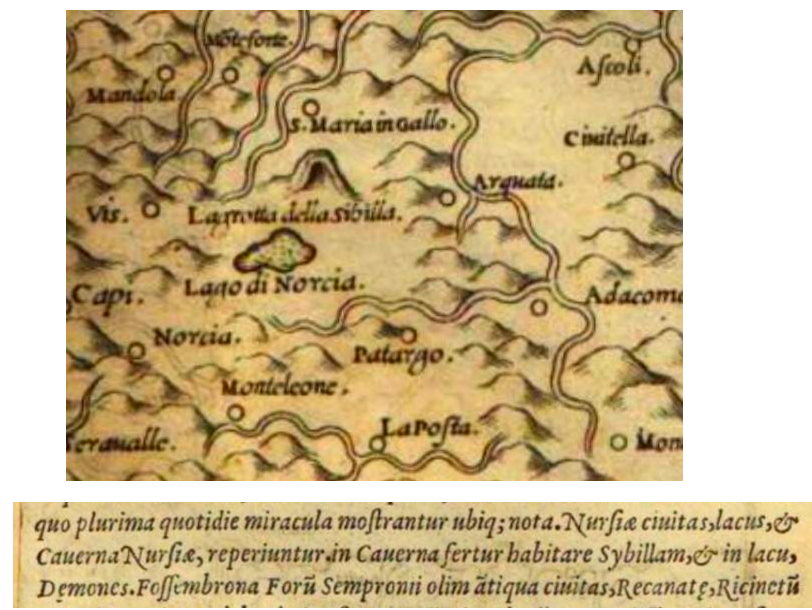

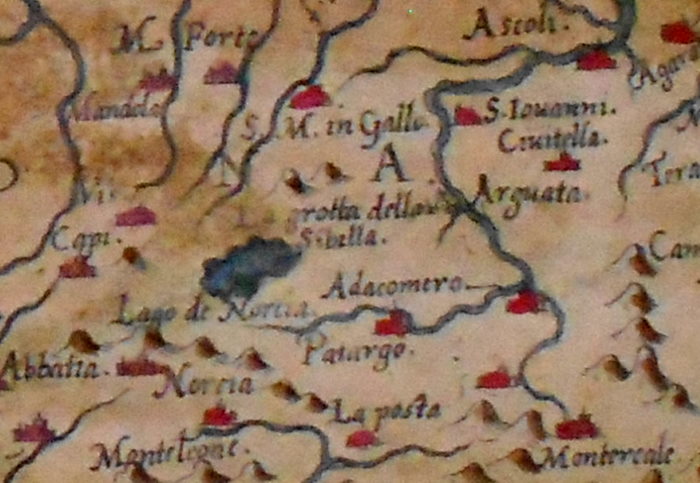

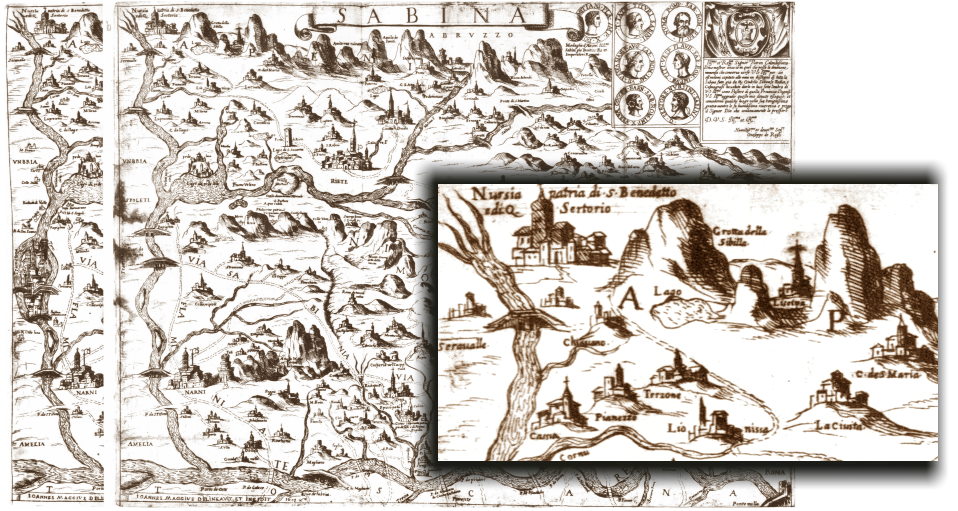

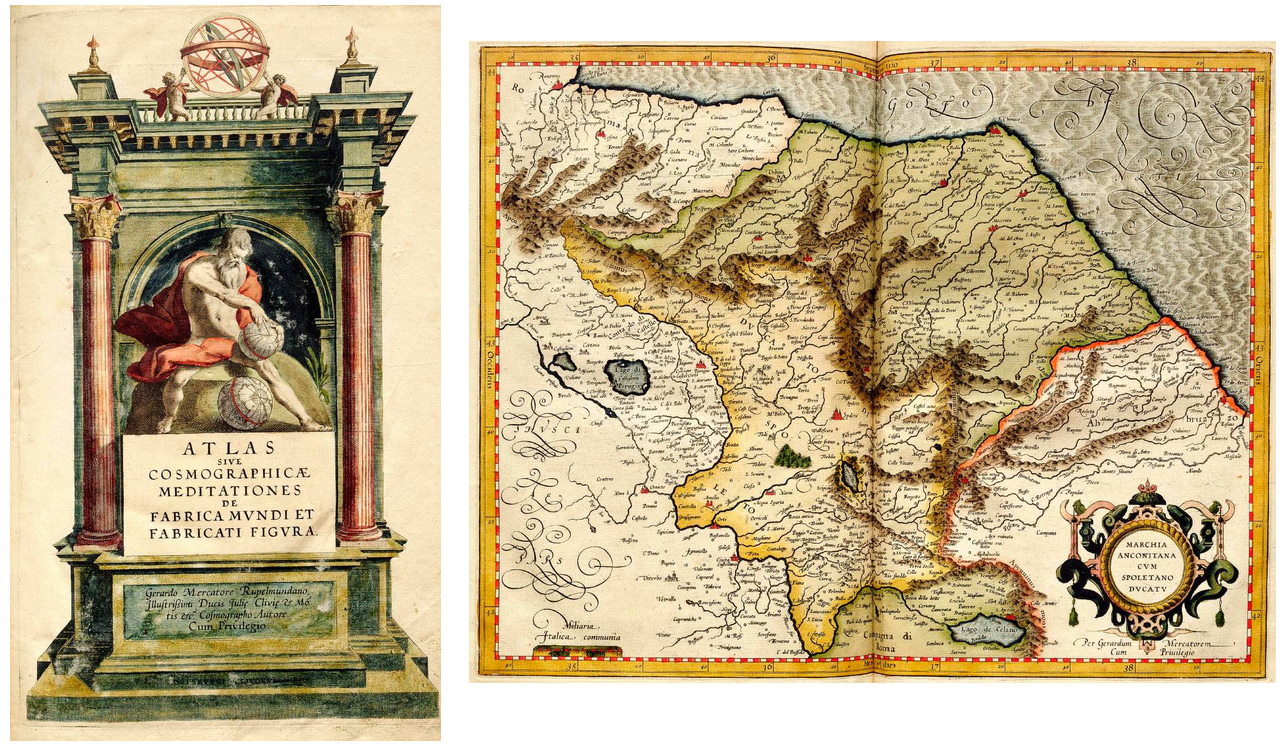

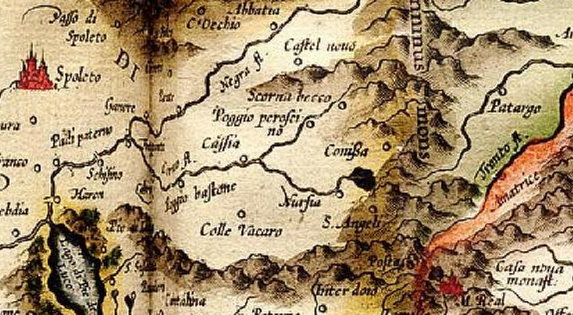

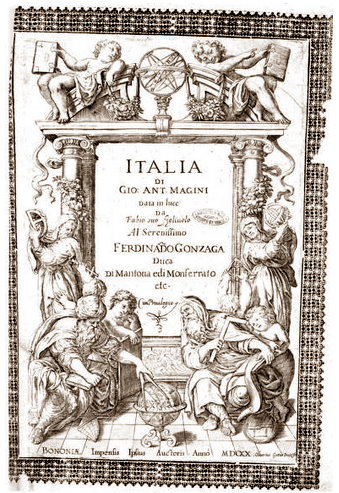

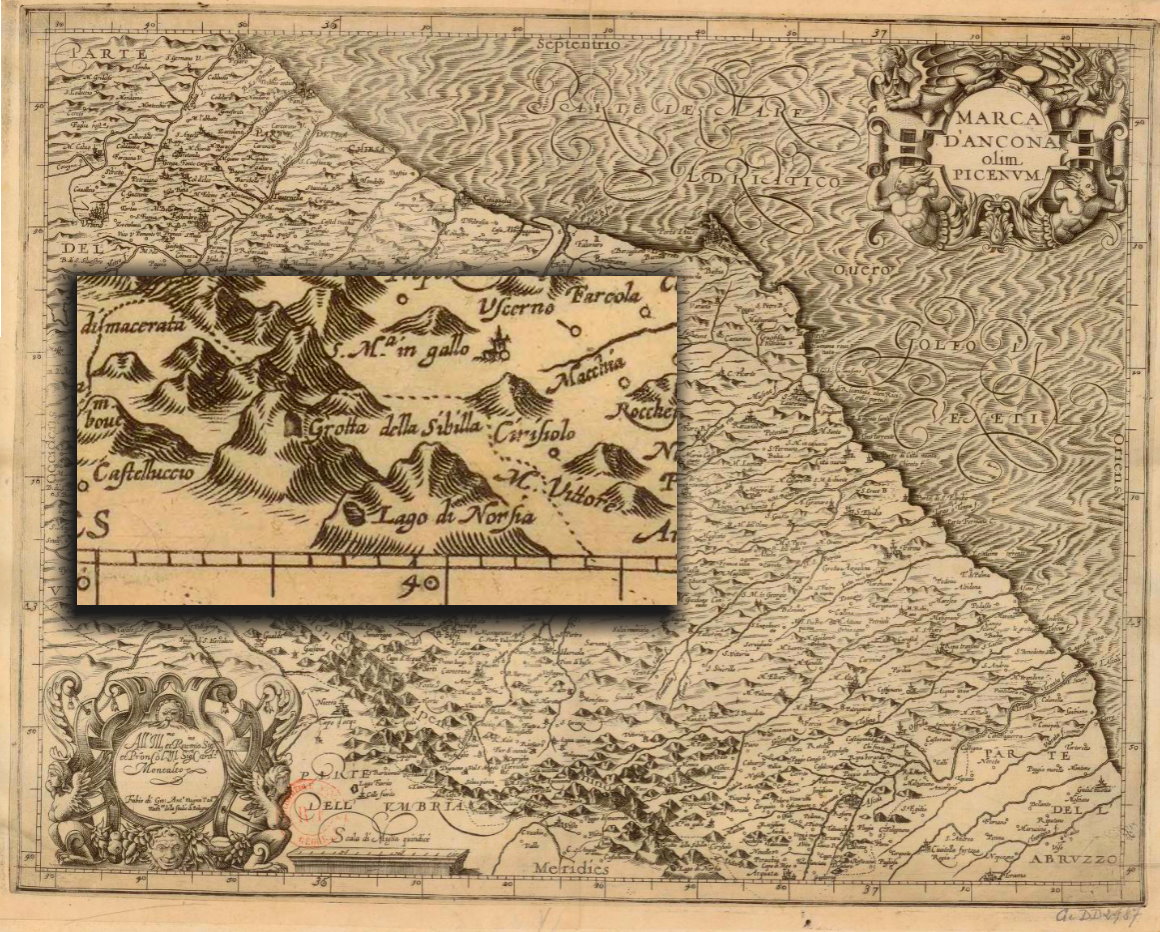

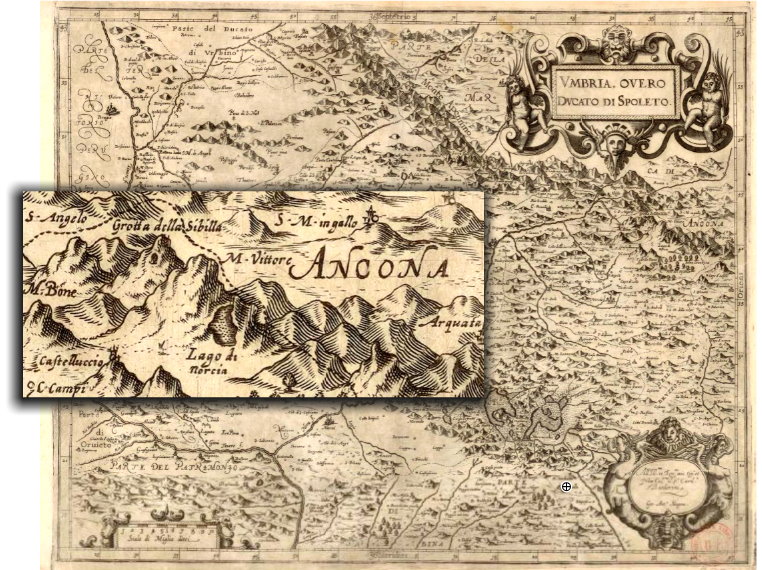

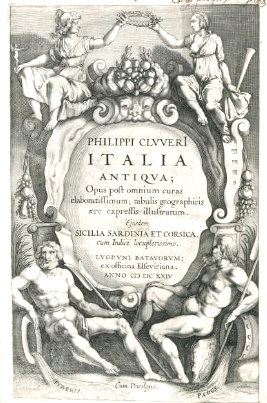

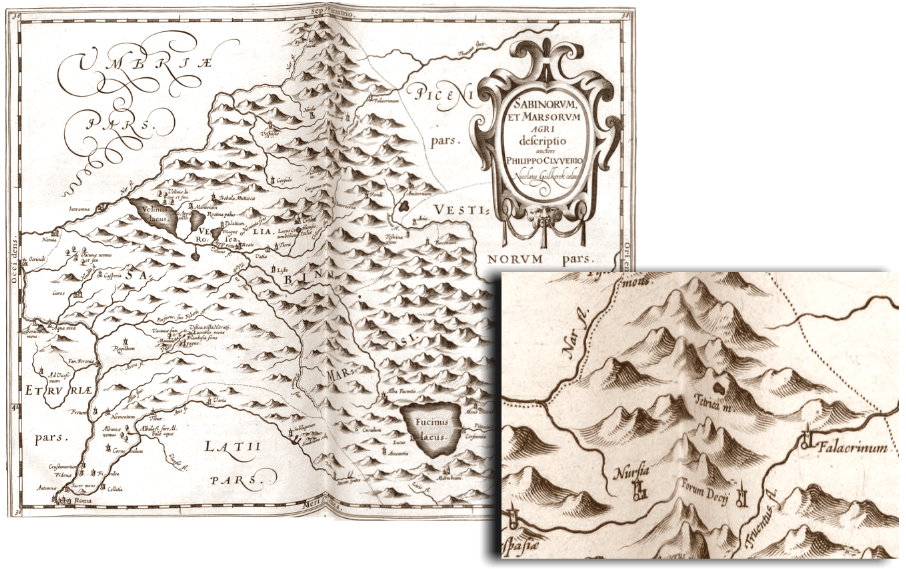

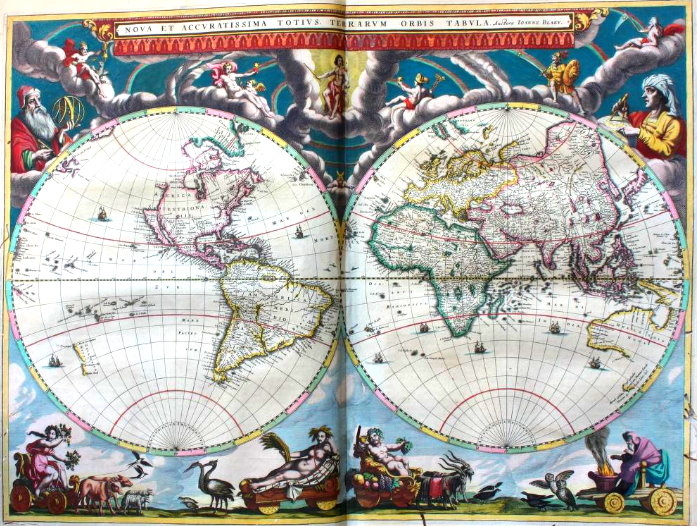

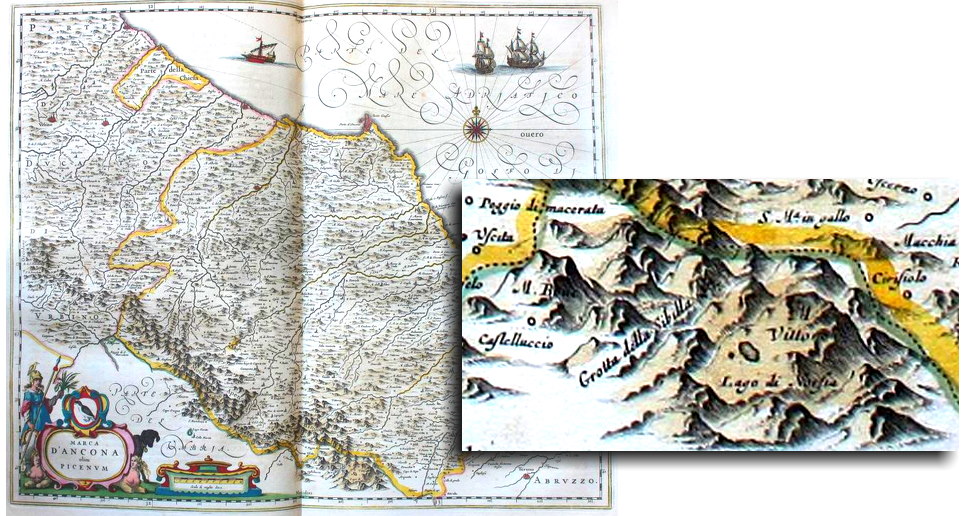

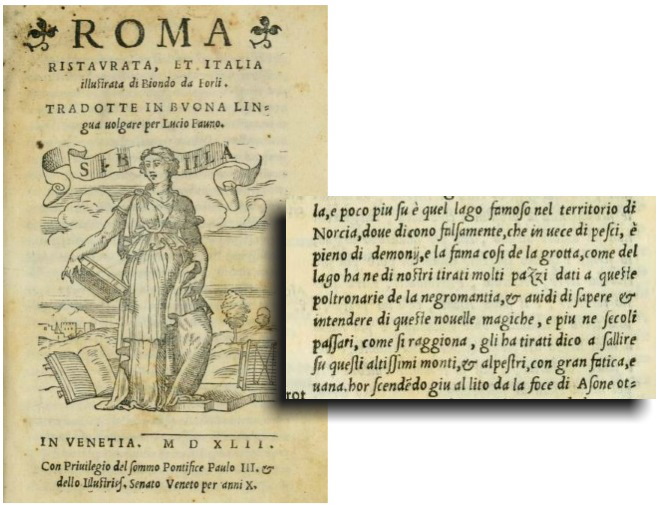

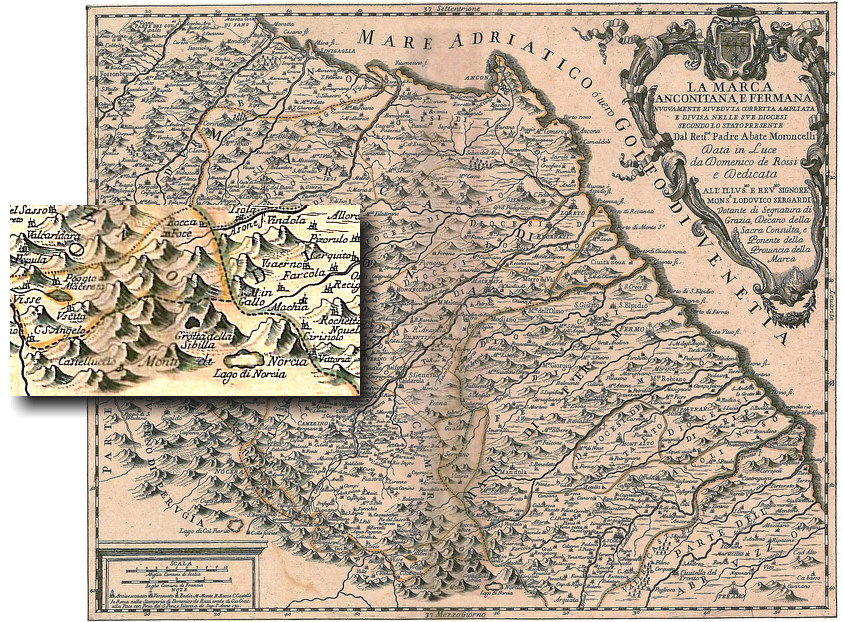

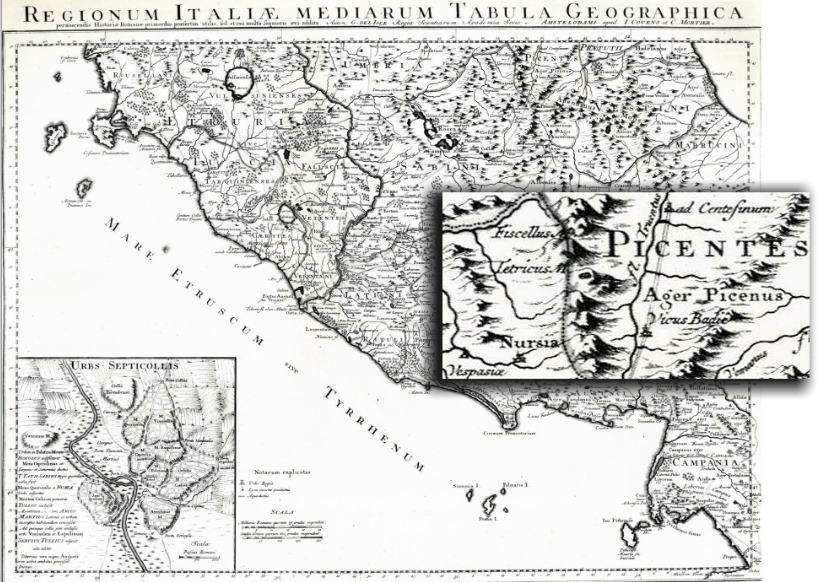

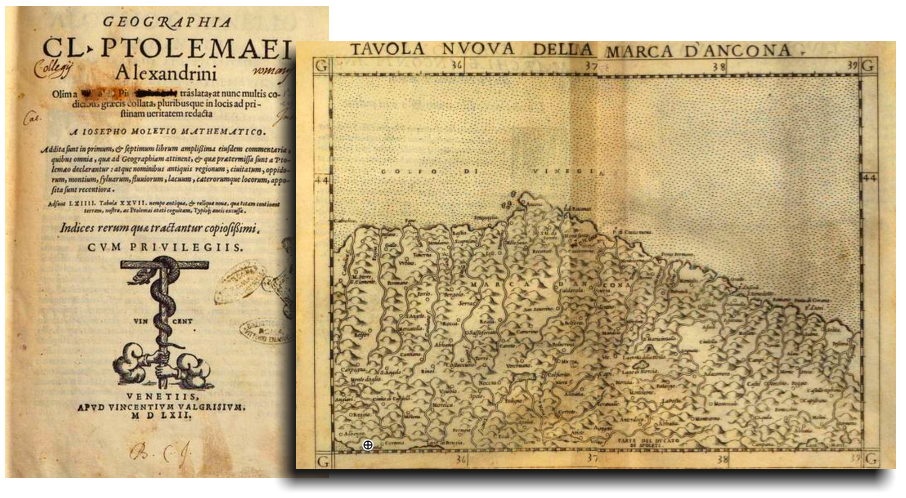

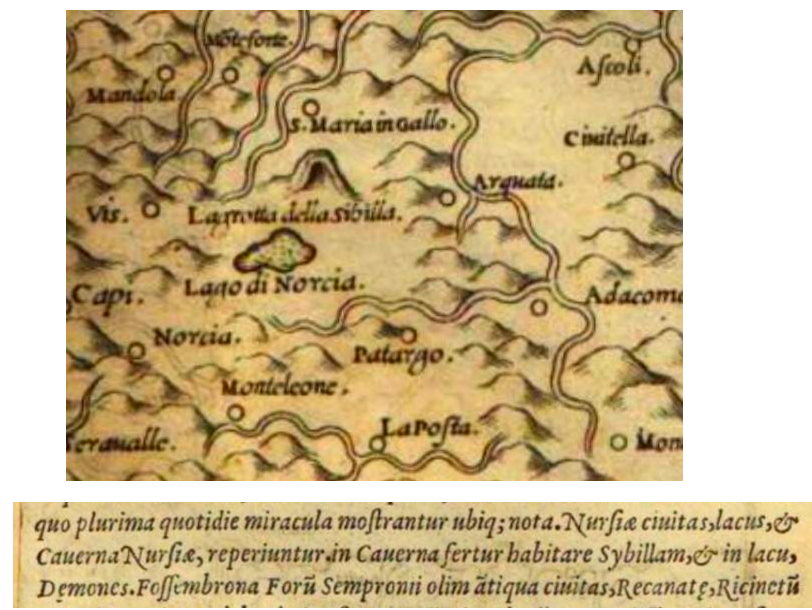

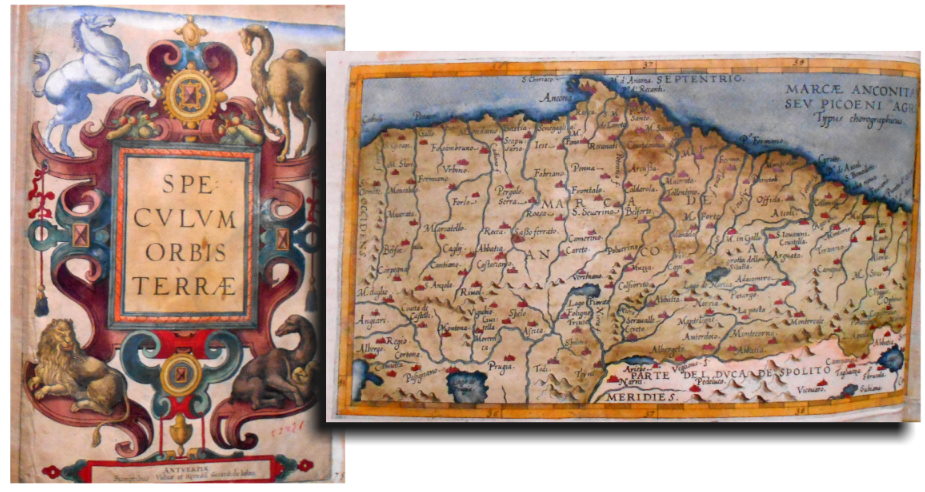

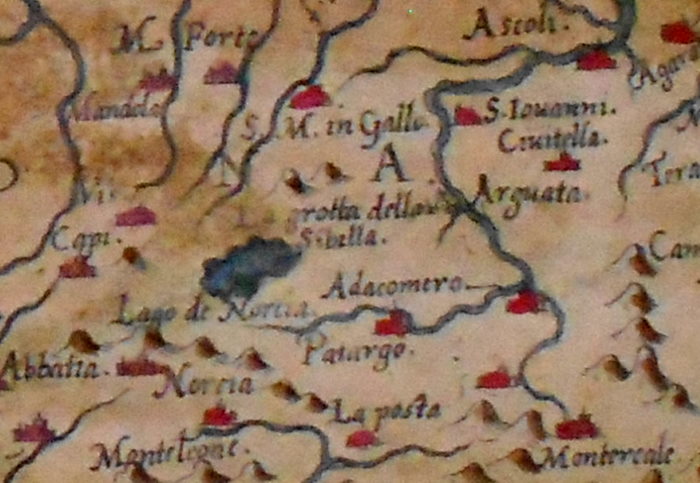

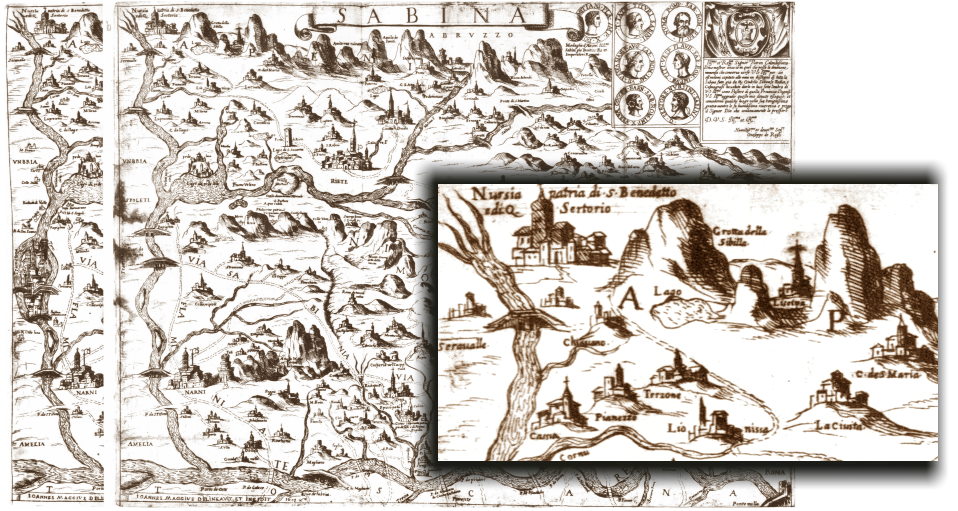

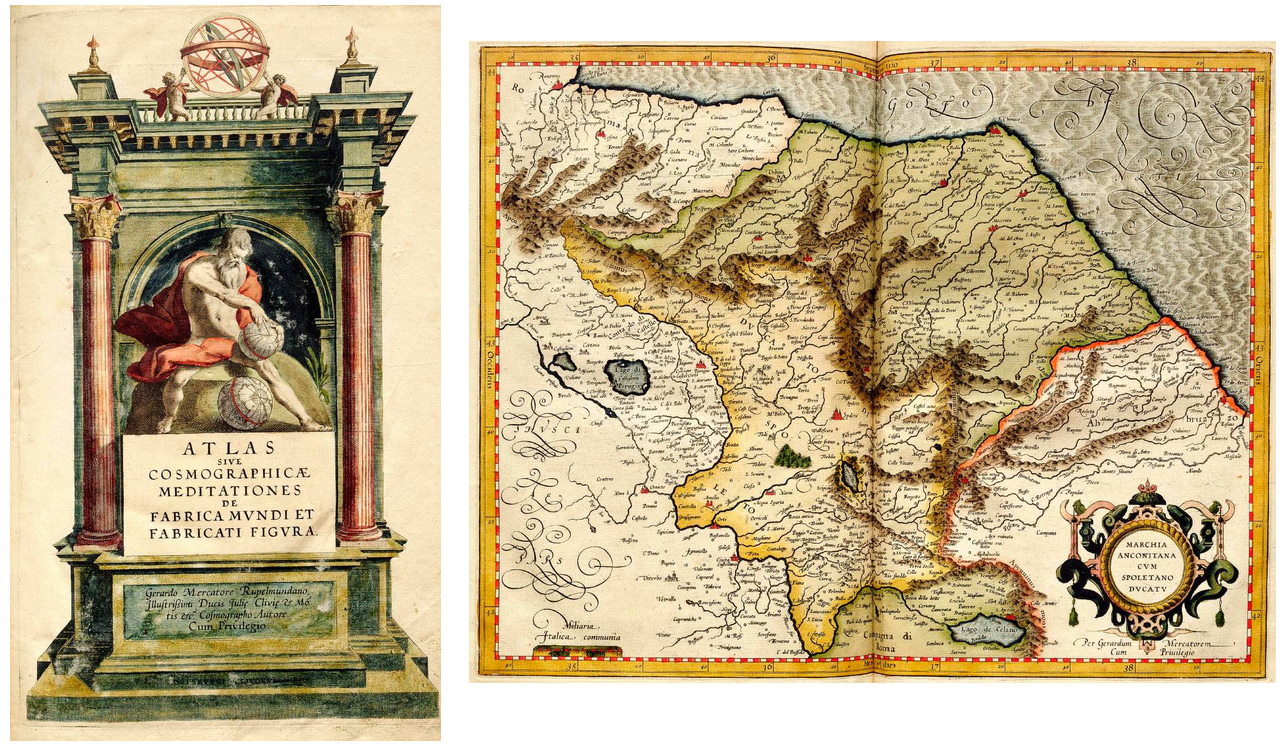

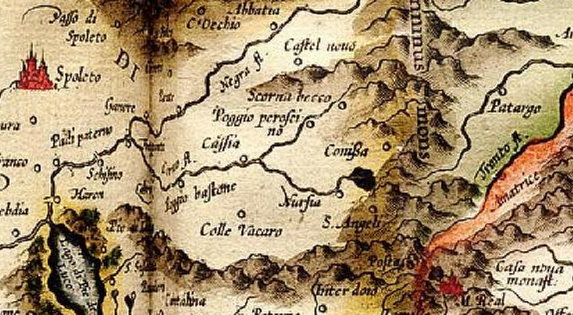

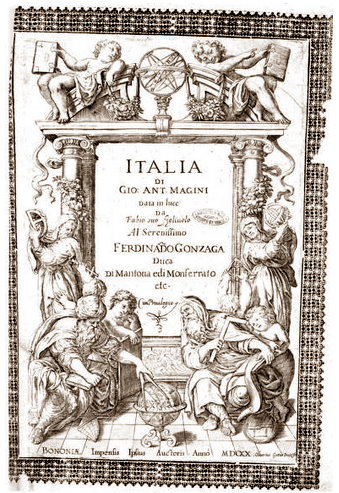

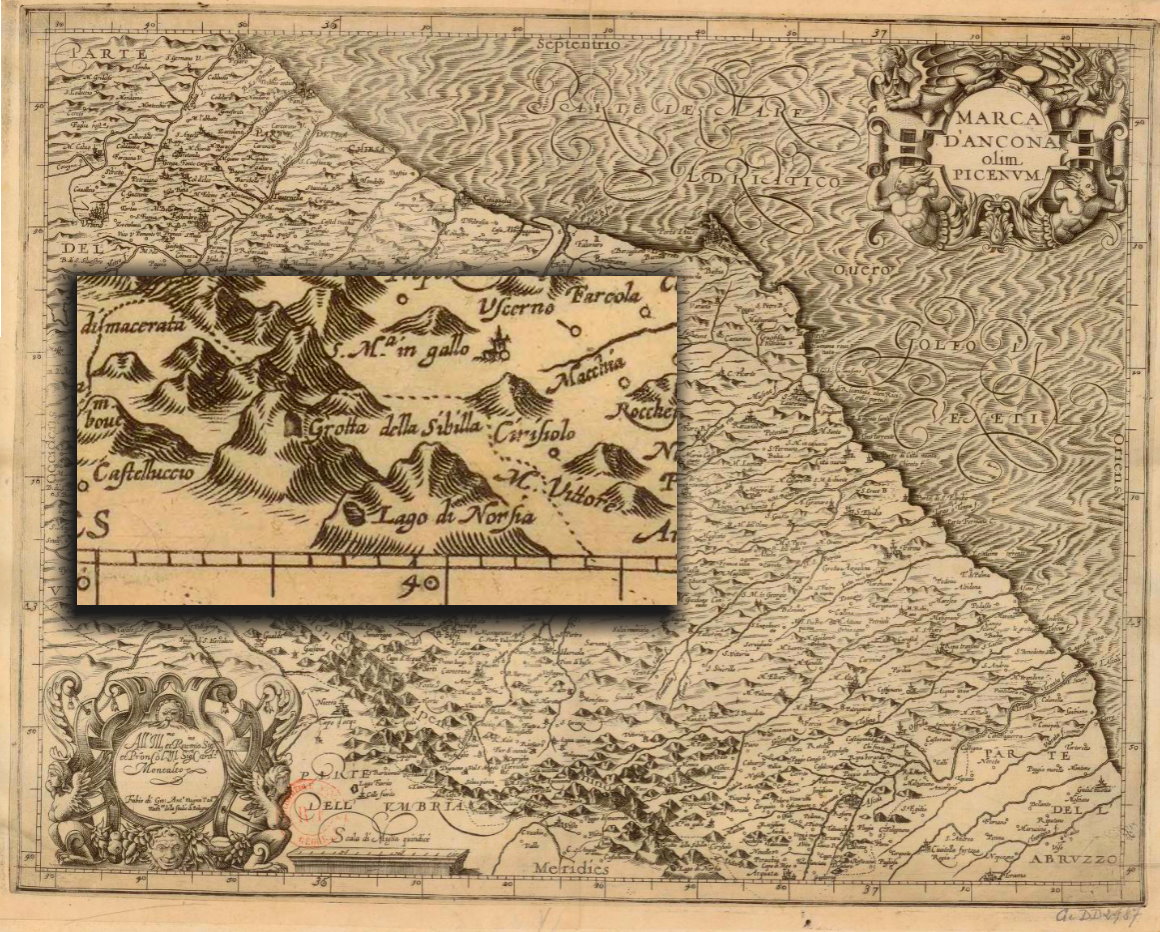

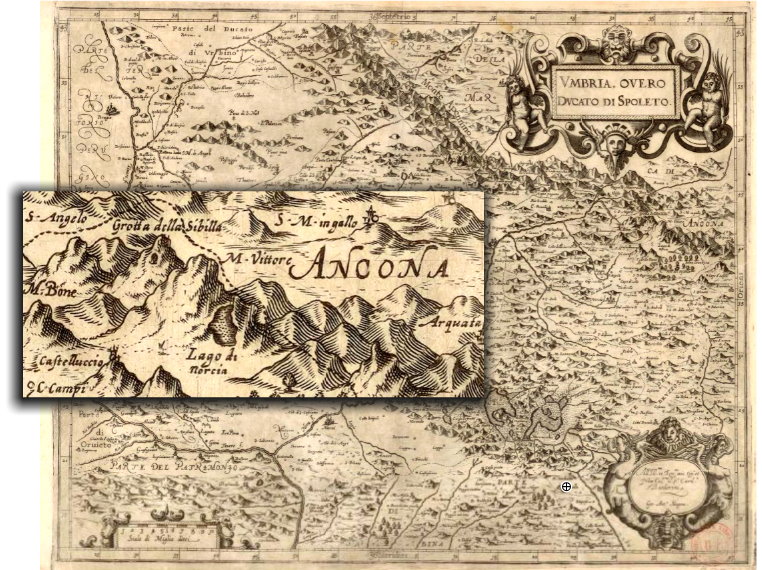

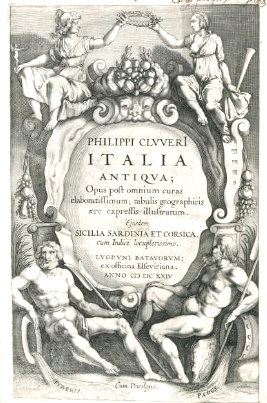

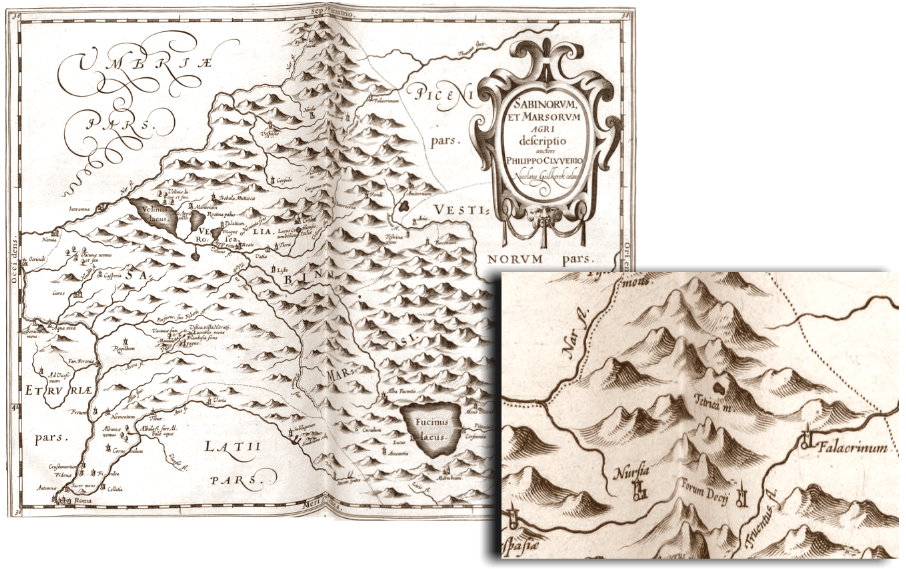

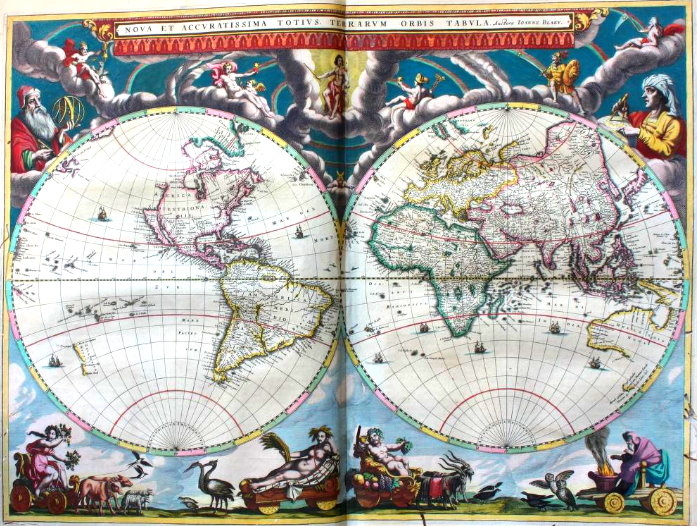

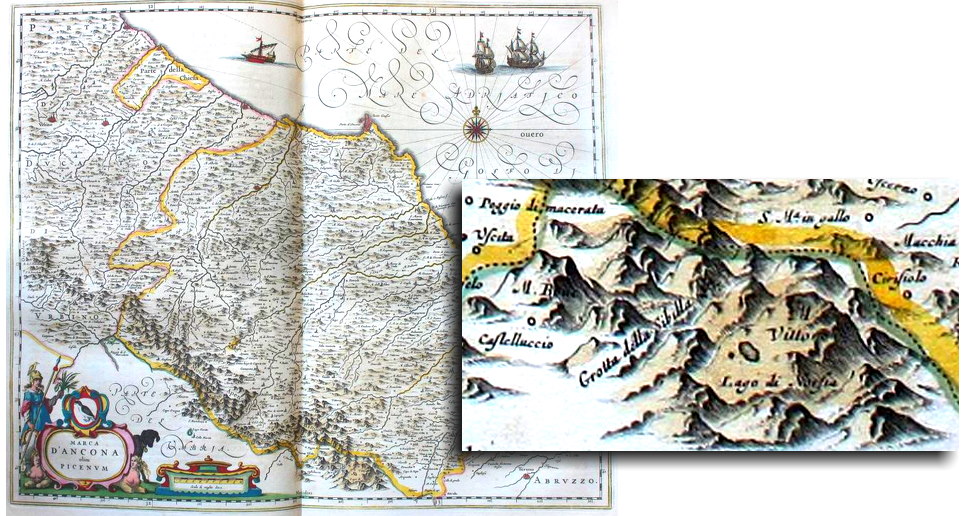

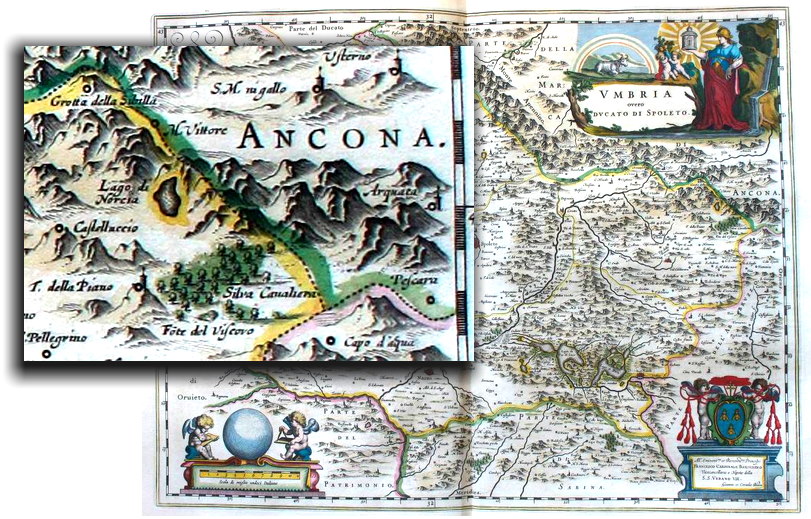

Pope Pius II Piccolomini, Flavio Biondo, Arnold von Harff, Leandro Alberti provide mentions about the gloomy Lake set amid the cragged cliffs of the mountains of the Sibyl. A single, ominous Lake, as portrayed in many geographical maps across the centuries: its likeness is depicted on the walls of the illustrious Gallery of Maps at the Vatican Museums in Rome; Giuseppe Moleti, in his edition of Ptolemy's "Geography" draws a single Lake, and an elongated version of it is presented by Gerard de Jode in his “Speculum Orbis Terrae”; it pops up from the map set down by Giubilio and Maggi in 1592, then it appears in Gerardus Mercator's “Atlas sive Cosmographicae Meditationes de fabrica mundi et fabricati figura”, in Giovanni Antonio Magini's “Italy - A General Description”, in Philipp Clüver's “Italia Antiqua”, and in Joan Blaeu's “Nova et accuratissima totius terrarum orbis tabula".

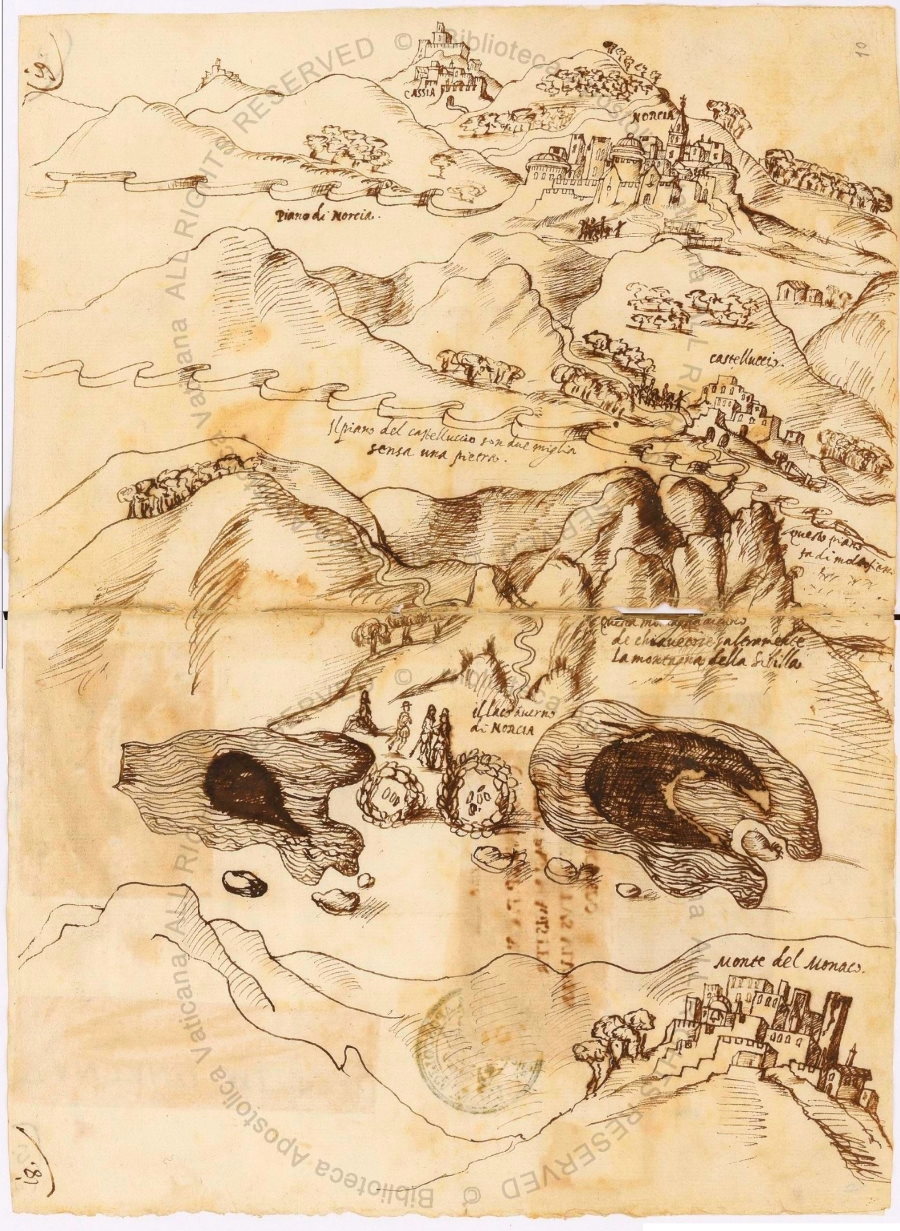

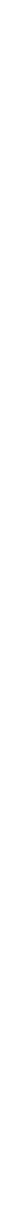

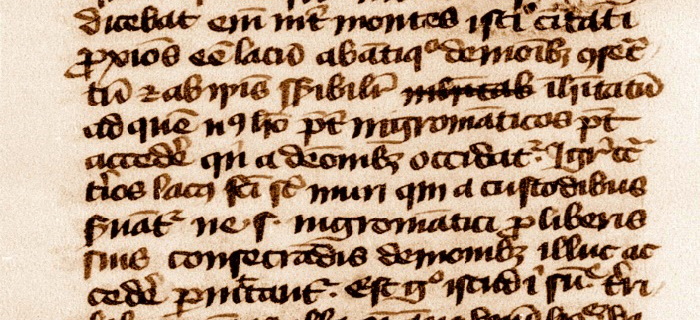

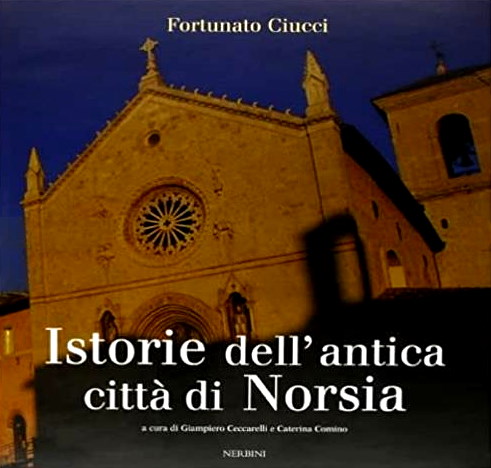

In all the listed literary and cartographic references, the Lake of Pilate is always one: a single, impressive Lake, concealed beneath the rocky arms of Mount Vettore. Only one instance, in the sixteenth century, provides us with a different vision: two scanty, separate Lakes, as attested in manuscript Vat. Lat. 5241, a graphical account of a visit possibly carried out during a hot, dry summer. But this account remained buried for centuries, hidden amid the many vellum folia which contained a collection of ancient Latin inscription, and was found and taken back to light only in 1982.

So, in past centuries, the usual shape of the Lake of Pilate was that of one basin, with temporary summer depletions which led to a partition marked by two smaller Lakes. Nonetheless, its fame across Europe concerned a single Lake: it was one, and it was necromantic, and it was legendary.

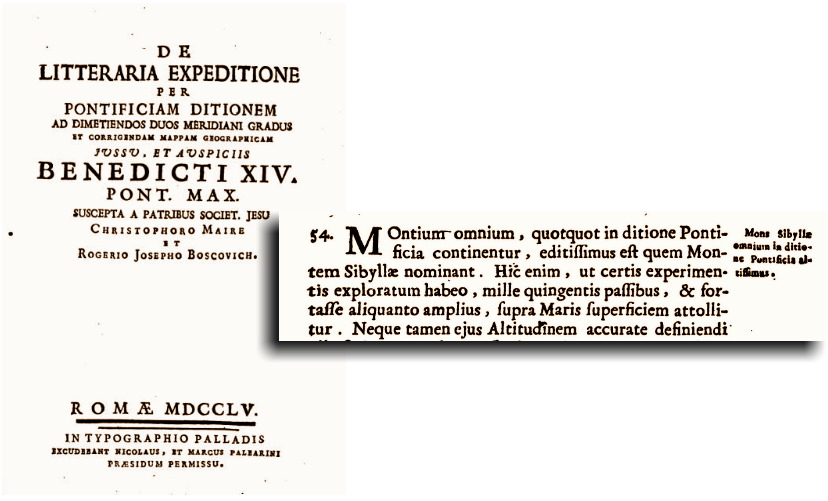

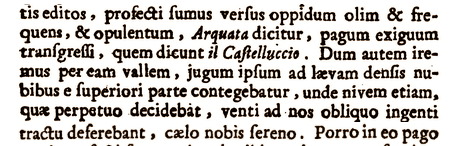

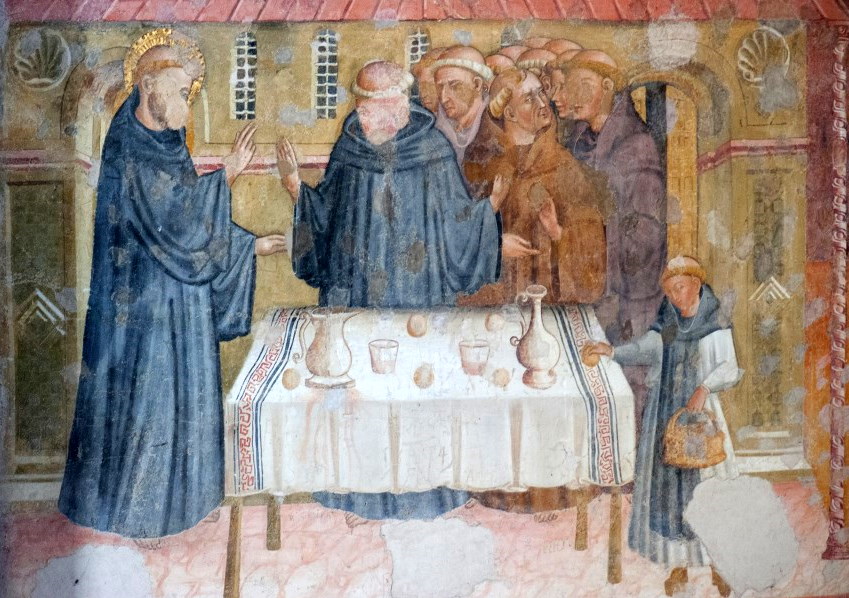

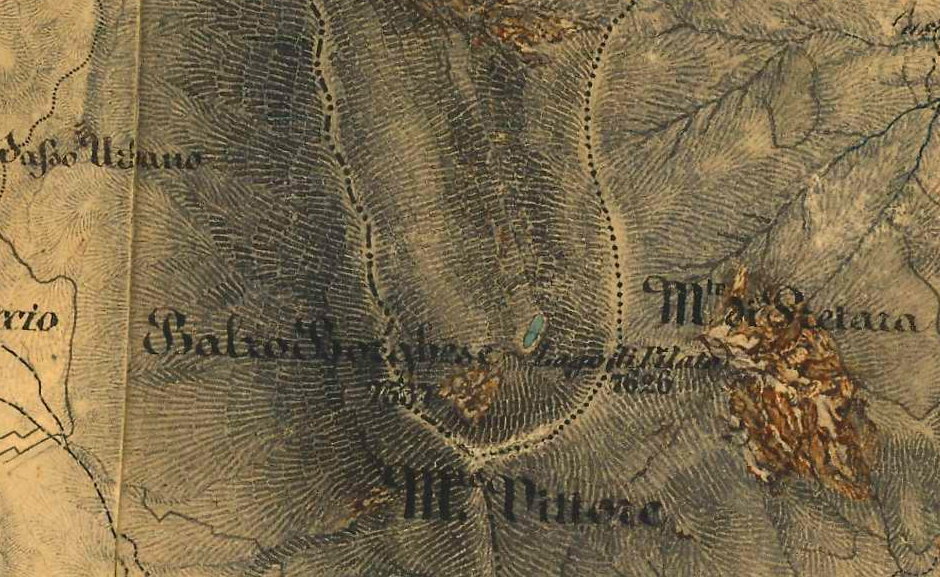

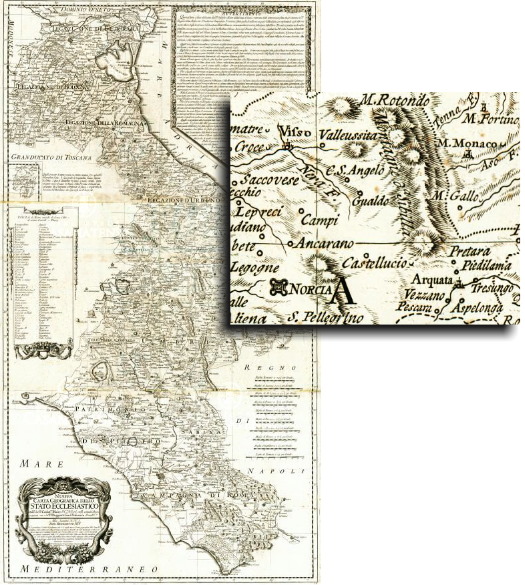

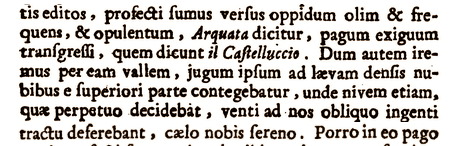

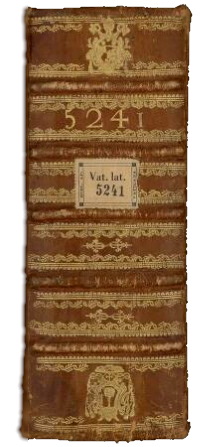

When we reached the seventeenth and eighteenth century, we found nothing different from the past: the Lake was still represented as a single Lake, consistently firm in its uniqueness, as we retrieve it in further maps edited by Silvestro Amanzio Moroncelli and Guillaume de L'Isle. We also retraced the steps of two great Jesuit cartographers, Christopher Maire and Ruggero Giuseppe Boscovich, with their misadventurous passage across the Sibillini Mountain Range: they did not see the Lake of Pilate, so that the basin is utterly missing in their comprehensive map of the Papal States. And we found another, isolated description of the Lakes in their depleted summer form: it is contained in the “Chronicles of the Antique Town of Norsia” by Father Fortunato Ciucci, who wrote that they appeared «in the form of spectacles», adding that «I saw from various signs that they come together making up a single lake; but in Summer, in the lack of running water, they split, so that they are seen in the shape of eyeglasses». But his text had no circulation at all: only four manuscripted copies of the "Chronicles" are extant, and they were never printed in a book, if not in a modern edition dating to 2003.

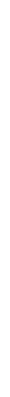

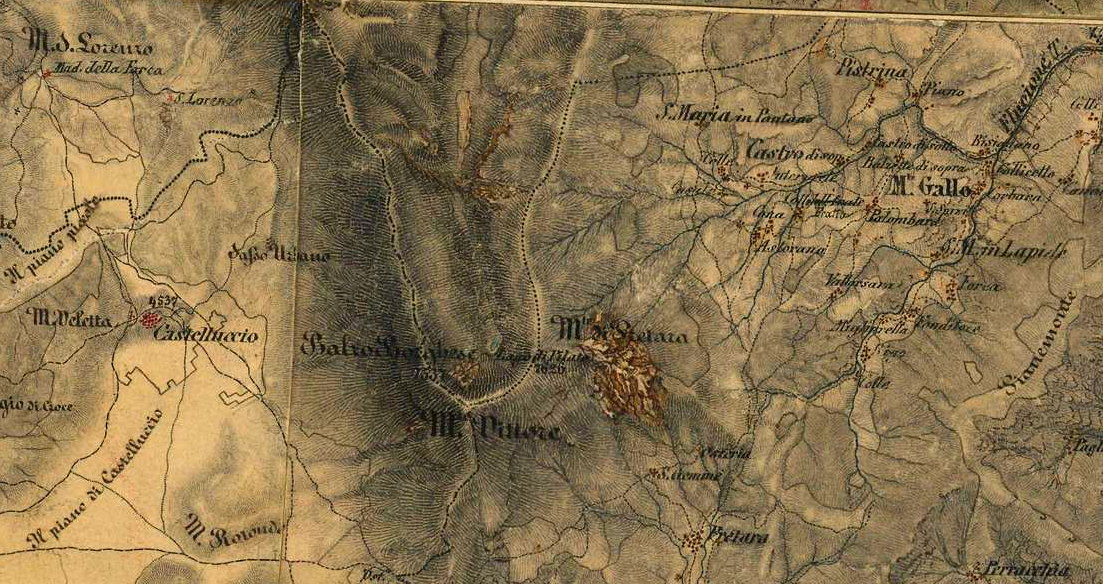

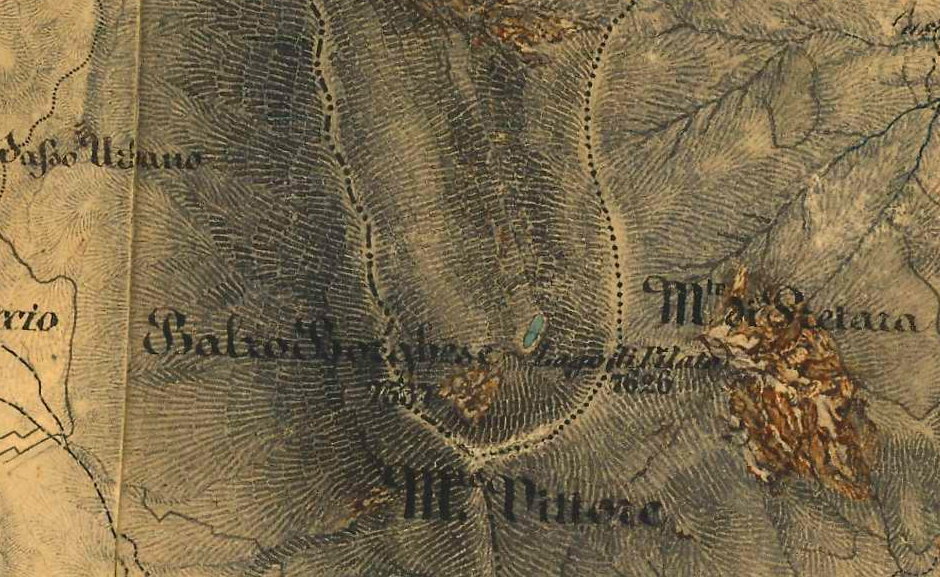

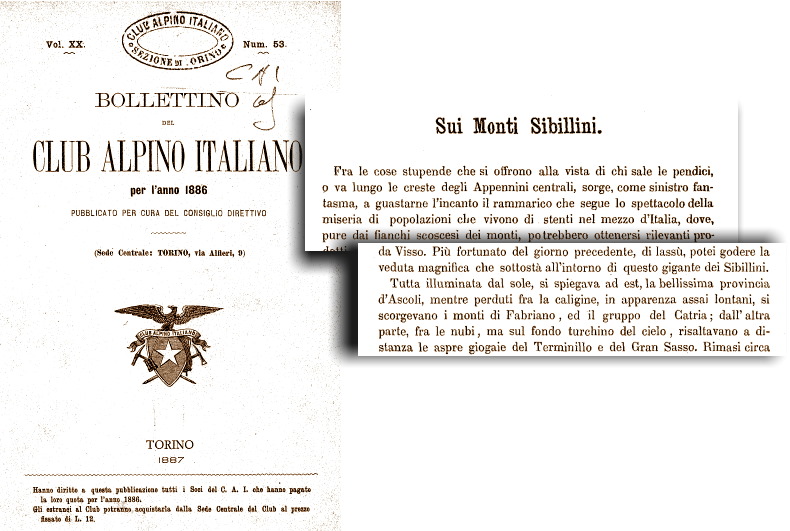

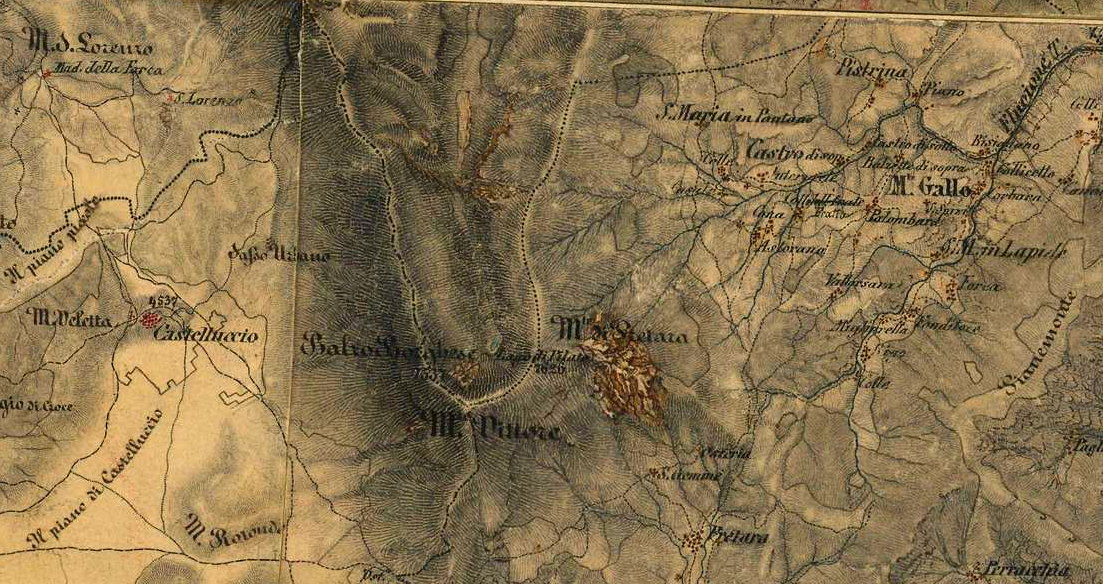

It is in the course of the nineteenth century that a change begins to be apparent, amid the Sibillini Mountain Range. However, no modification is still visible when a geographer of the Imperial and Royal Military Geographical Institute of Austria draws a gorgeous maps of Tuscany and the Papal States: between 1841 and 1843, the Lake is still seen by the professional eyes of Giovanni Marieni as a single basin, and so reported in the relevant cartographic sheet.

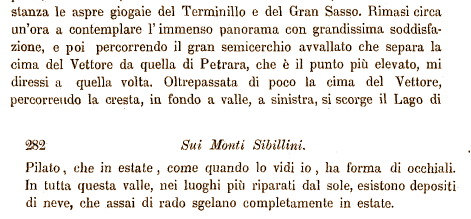

The second half of the century brings in a new shape for the Lake. Initially, nothing seems to have undergone any change: in the summer season, the Lake appears split in two smaller ponds as it occurred in past centuries, too. We can read about its shape in the report written during the summer of 1877 by Count Girolamo Orsi, an illustrious member of the then-young Italian Alpine Club: «between the two branches [of Mount Vettore], at the very bottom of titanic ravines, the Lakes of Pilate are found», he writes, «the Lakes of Pilate, and their deep-blue waters, and the frightful ravine nearby». And, in 1887, Giovanni Battista Miliani also sees the two summer Lakes: «down in the valley on the left side, the Lake of Pilate is seen; in summer, as when I saw it, it has a shape of spectacles».

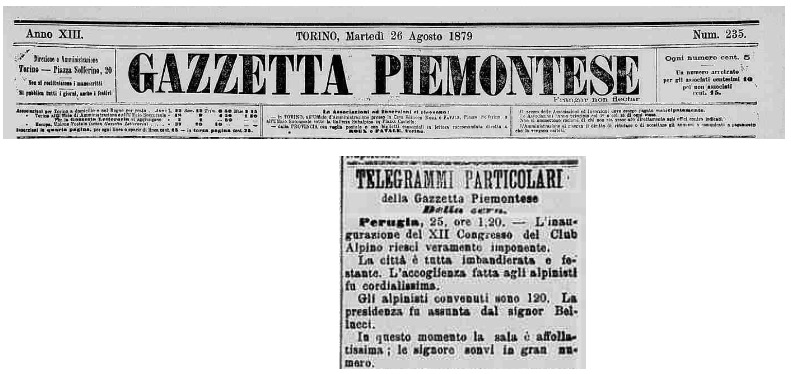

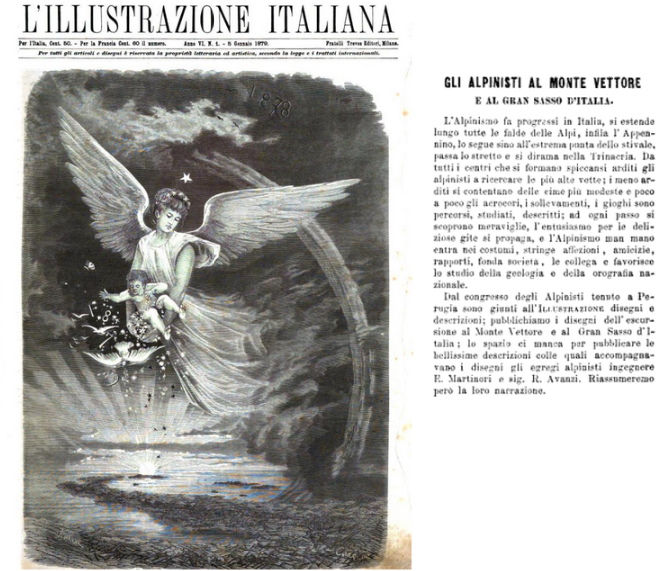

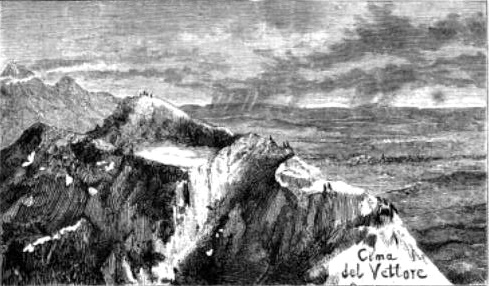

And there are also occasions in which the Lake still retains its original, impressive appearance as a single mirror of waters. When the members of the Italian Alpine Club visited Mount Vettore in 1879, they beheld the ancient vista already described by Antoine de la Sale more than four hundred years earlier: a large, single Lake, ominously nested within the arched crests of the mountain, the way it appears in the drawing published by "L'Illustrazione Italiana" at the time. A vision also confirmed by another report, independently written by Countess Lucia Rossi Scotti, who had joined the alpinists on their climb that day: «... the greenish, gloomy Lake of Pilate, lying in that gorge out of the melting of snows...».

But at the end of the nineteenth century time has come for the Lake to undergo a change. For unknown reasons, snows and rains appear not to be able to fill it up to its single-basin shape anymore. From now on the Lake of Pilate will increasingly begin to turn into the two Lakes of Pilate we know today.

The most accurate description of the new typical shape of our legendary basin is set down by Italian philologist Pio Rajna in 1897: «the Lake appeared to me divided in two elliptical mirrors [...]. The comparison with a pair of spectacles [...] is truly pictorial». An usual occurrence, in summer. But that specific summer plenty of snow was there, accumulated on the sides of Mount Vettore's glacial cirque, manifestly without being able to confer the Lake its larger, single shape:

«I found snow in fair quantity around the lake; and normally Mount Vettore never denies this garniture to itself, as Antonio told me. In Foce (a small hamlet lying in the valley underneath) people told me that once there was a period of nine years when a lack of snowfalls was registered in winters, too, but this occurred and ended twenty years ago».

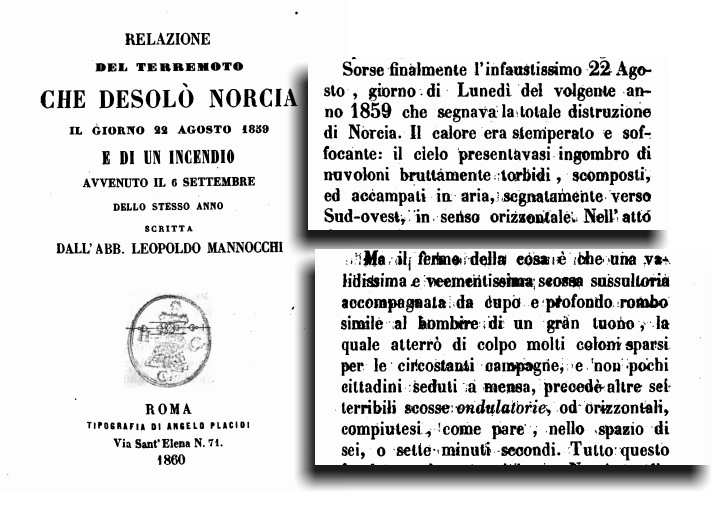

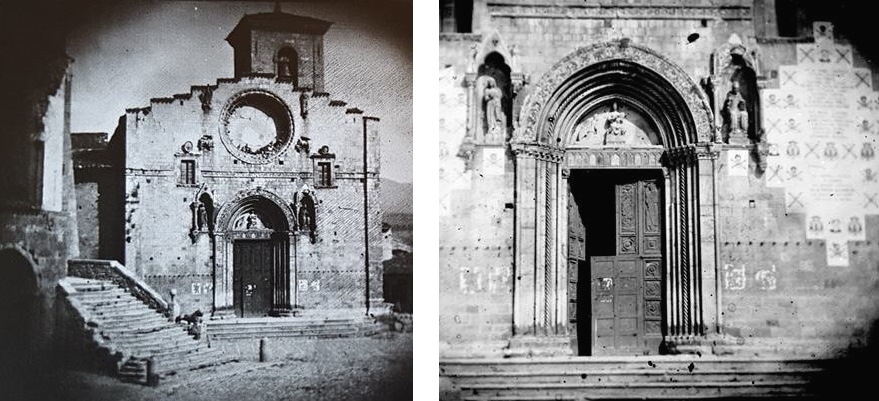

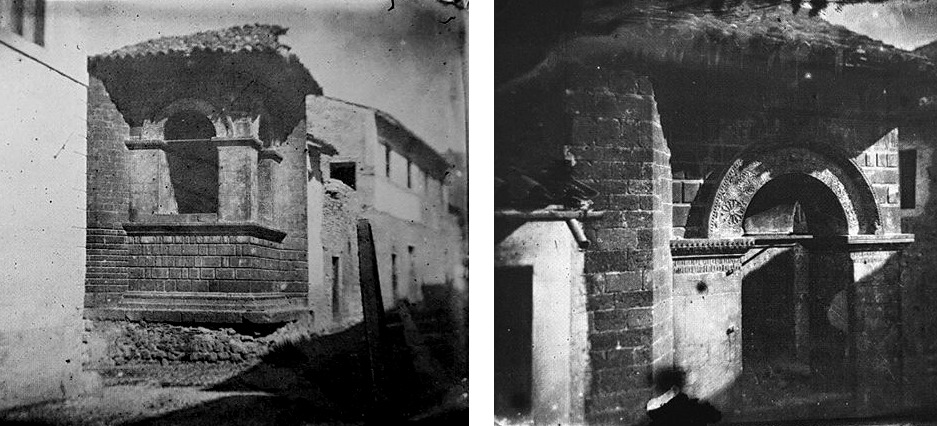

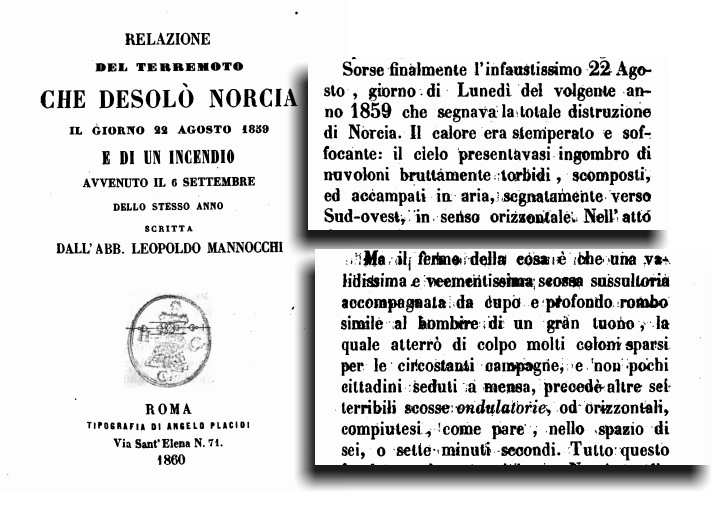

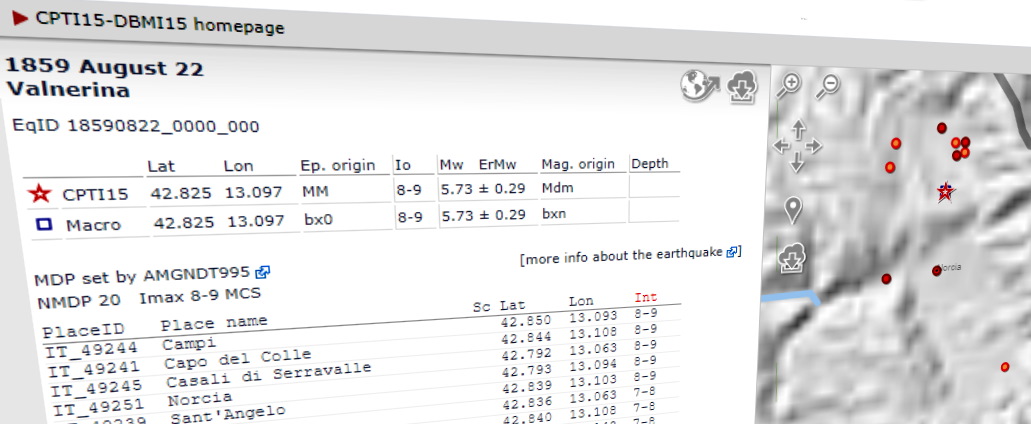

Had anything happened to the Lake of Pilate? According to Rajna, «today the lake is not what it was in past times anymore»: some forty years earlier «it broke the natural dike at its front, a barrier that never formed again. So Antoine de la Sale beheld a lake with a significantly different appearance, and deeper». And, truly enough, in 1859 a great earthquake struck the territory of Norcia: was it the cause for a dramatic collapse of the northern side of the glacial basin which holds the necromantic Lake? Did the seismic waves change the appearance of the basin forever, with an inability to return to its single form even when snow was present?

As we detailed in the present research paper, we cannot tell. The 1859 earthquake was certainly strong enough to turn Norcia into a heap of ruins; yet, its magnitude and epicentre do not seem to feature the attributes and power required to affect Mount Vettore in so dramatic a way, and no reports on such conjectural event have ever been found in local records as yet. Furthermore, if such an event had actually happened, the members of the Italian Alpine Club could not have experienced a vision of a single Lake as late as 1879, as reported by an Italian magazine of the time.

Anyway, despite its final, occasional appearance as a single basin, starting from the second half of the nineteenth century the shape of the Lake of Pilate was destined to tread a path of growing duplication, and increasing water depletion: the Lake will begin to present itself as a basin substantially split in two smaller ponds, either utterly parted or joined by a narrow strip of water. In summers and winters. Because, during winters, it usually will not regain its original, single form. A sign of growing scarcity of snowfalls and rainfalls, and possibly of variations in the physical configuration of the rocky basin.

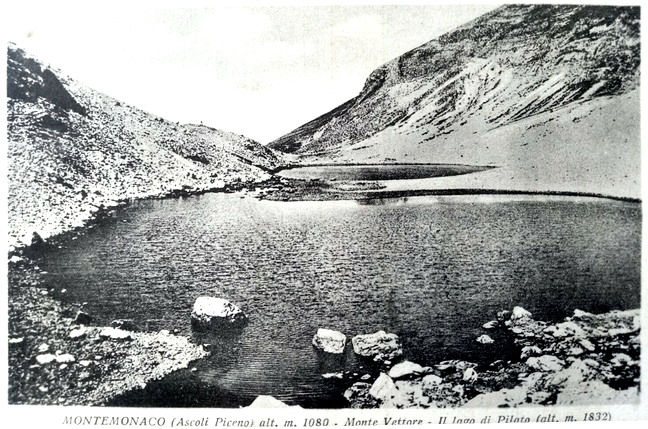

The late nineteenth-century cartography drawn by the Italian Military Geographical Institute shows an elongated Lake now visibly indented at the middle, ready to part in two fully distinct ponds. The same deep notch will be portrayed by Cesare Lippi-Boncambi in his drawing dating to 1947. And though other military maps edited in 1952 present the Lake in its flourishing though elongated form, actual reality at that time was markedly different: vintage postcards and aerial photographs cannot but ascertain that the Lake of Pilate had already changed its shape into two smaller ponds, increasingly affected by a significant lack of water supply and possibly overwhelmed by remarkable masses of debris ceaselessly falling from the adjacent crests.

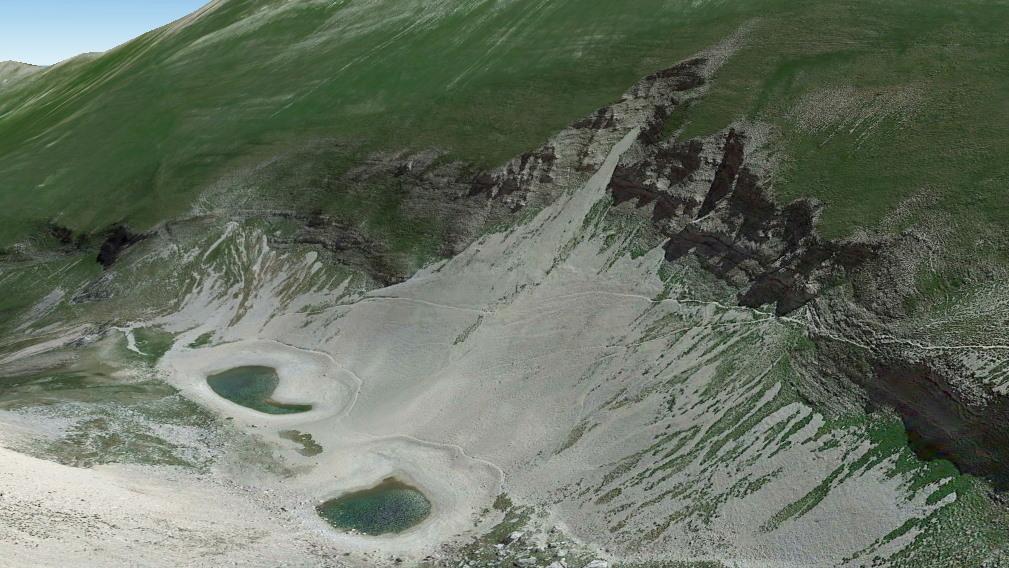

Partition, depletion and insufficient provision of water. A condition that will be repeatedly observed across the first decades of the twenty-first century. The pictures of the Lakes, sadly shrinked to two tiny ponds, and the portraits of a glacial valley utterly deprived of any trace of water, as happened in 2017 and 2020, are truly heartbreaking.

In the present paper, we summarized the potential reasons which may be at the origin of such severe depletion. We could not confirm Pio Rajna's piece of information concerning a mid-nineteenth-century collapse of the Lake's front dike. We reviewed the position of researchers as to the possible drainage of waters from the bottom of the basin into the underlying bedrock, owing to new cracks and fissures potentially produced in the soil by the 2016 earthquakes; but accurate surveys have shown no evidence of such a drainage at the site.

So we identified two main effects, both of a nasty nature, which are affecting the health conditions and overall shape of the Lakes of Pilate. Two adverse effects that are gradually bringing the mountain basin to a fated, inexorable termination.

A first, most critical cause for the increasing depletion of the Lakes of Pilate is climate change. And this statement, alone, resounds in our ears as a sentence of death.

From the fourteenth century to the middle of the nineteenth, the Little Ice Age, a climate condition which affected Europe and was marked by moderately lower temperatures as compared to the previous time periods, ensured an optimal water feeding to the Lake of Pilate: winters were colder, snowfalls were abundant, plenty of accumulated snow was present on the Sibillini Mountain Range, and copious rainfalls helped the Lake to preserve its water balance.

Thus, throughout many centuries, and as attested by the many sources we explored in the present research paper, the Lake of Pilate was a well-fed, single, impressive, necromantic mountain basin. With only temporary depletion affecting the shape of the Lake during the good season.

Then climate began to change.

The effects of man-driven changes started to manifest from the mid of the nineteenth century onwards, with a rapid rise of temperatures around the globe. And the Italian Apennines, like the whole of Europe, were affected, too.

The Lake of Pilate began to mutate: the transformation process into two separate Lakes was gradual, as snowfalls became increasingly less intense on average, and the same happened to rainfalls.

In August 1876, Count Girolamo Orsi was able to behold, in the glacial cirque within Mount Vettore, «the Lakes of Pilate [...], fed by an extended volume of ice, the seed of a persistent glacier, which hides itself down there from direct sunlight. [...] The perennial snows down there, [...] in the gorge set northeast of the peak of Petrara; the same snows that feed those Lakes...» (in the original Italian text: «i Laghi di Pilato, alimentati da quella estesa lente di ghiaccio, embrione di un ghiacciaio perenne, che laggiù si nasconde ai raggi del sole. [...] Quelle nevi perpetue interposte ai tre culmini, là in quella gola nord-est del Petrara, che danno alimento a quei, laghi»).

And Giovanni Battista Miliani, in 1886, wrote that «across all the valley [where the Lakes of Pilate lie], in the spots most sheltered from direct sunrays, accumulated snow persists, which only seldom melts and vanishes in summers» (in the original Italian text: «In tutta questa valle, nei luoghi più riparati dal sole, esistono depositi di neve, che assai di rado sgelano completamente in estate»).

Today, those perennial snows exist nomore, thoroughly erased by the scorching action of the summer heat generated by global warming: the very same warming that is killing glaciers all over the world.

A process which began to be noticeable at the end of the nineteenth century, as reported by Pio Rajna in his writings:

«I found snow in fair quantity around the lake; and normally Mount Vettore never denies this garniture to itself, as Antonio told me. In Foce [a small hamlet lying in the valley underneath] people told me that once there was a period of nine years when there a lack of snowfalls was registered in winters, too, but this occurred and ended twenty years ago».

[In the original Italian text: «Ho trovato neve in discreta quantità dattorno al lago: e per solito il Vettore non si priva mai, come dice Antonio, di questo ornamento. A Foce mi si è detto tuttavia esserci stato un periodo di nove anni, finito da un ventennio, in cui neve non s'ebbe neppure in inverno»].

So the Lake indented and then parted, two distinct Lakes appeared, and not only in dry summers but all year long, and all years. And, as global warming grew, snow and rain became unable to sustain the basin's needs in terms of water, with scant supplies and periods of severe droughts.

The result of this grievous process is emptiness and dryness.

However, this is not the only effect which is leading the Lakes of Pilate to an irrevocable death. Because a second, most severe cause is landslides.

Like deadly claws, two major historical landslides loom over the Lakes of Pilate from the western and eastern sides of Mount Vettore's glacial cirque. For centuries and centuries they have been sending rocks and rubble and debris from the high cliffs straight into the waters underneath. And the eastern landslide, in particular, has gradually built up a central ridge, which splits the original Lake in two different ponds.

So the bottom of the basins is raising and raising, across many centuries and the multiple earthquakes that certainly provide a contribution to the acceleration of the long, historical, uninterrupted process of filling-up. A process that, possibly, experienced some sort of advancement between 1879 and 1897: from the vision of a healthy Lake as seen by the Italian alpinists to the parted, fully-separate Lakes observed by Pio Rajna, despite the presence of melting snow.

Landslides and bottom raising. Climate change and water depletion. Nasty effects which suffocate and choke the basin set amid the cliffs of Mount Vettore.

That's why we are now facing the impending, final, irrevocable death of the Lakes of Pilate.

At all appearances, the Lake of Pilate of past centuries, in its illustrious, single shape as it was celebrated for many hundreds of years across Europe, is extant nomore. And it will never come back.

And the Lake as we ourselves know it today, in its lesser form made up by two smaller, separate Lakes, is currently dying.

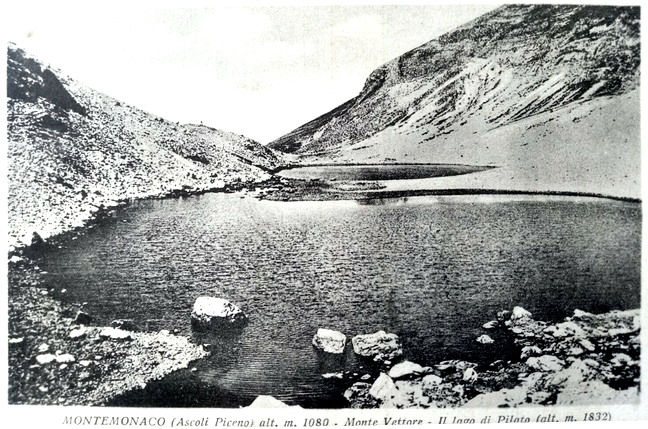

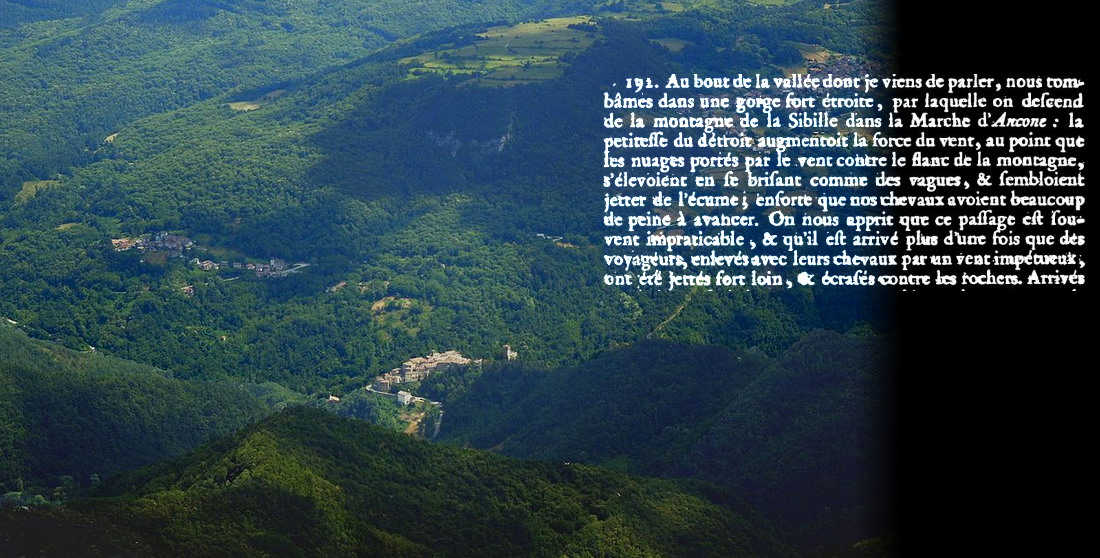

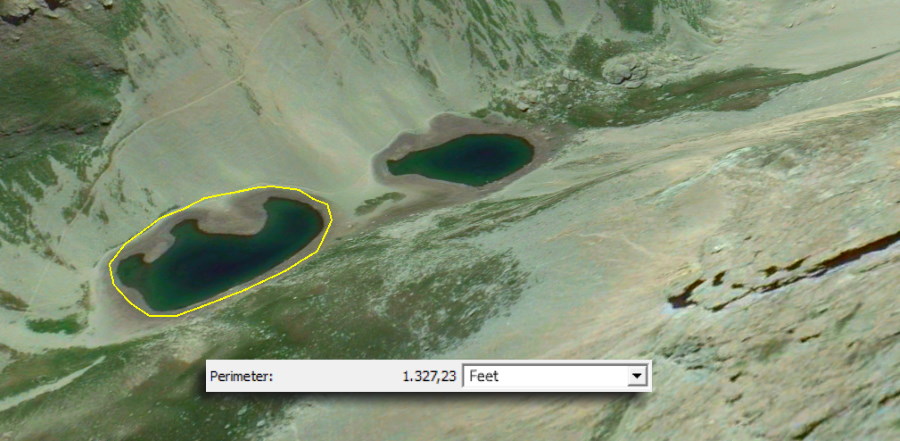

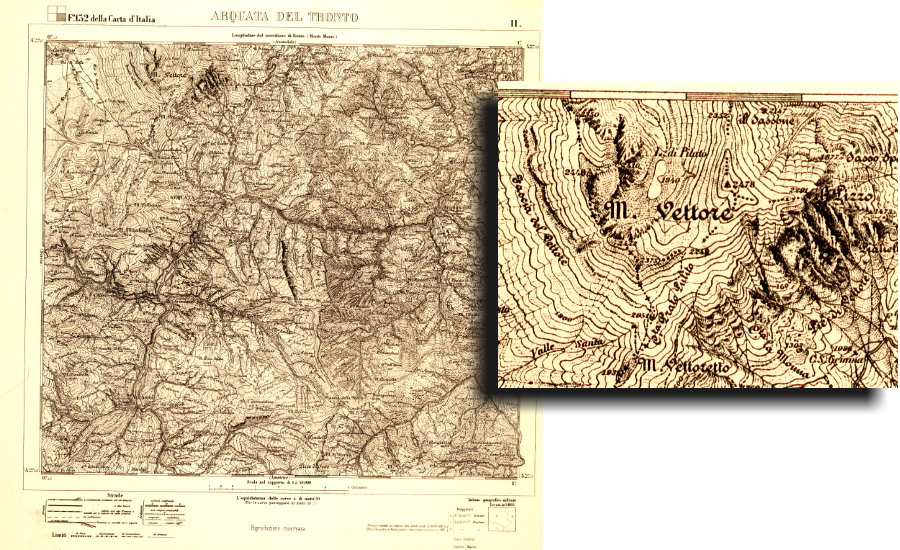

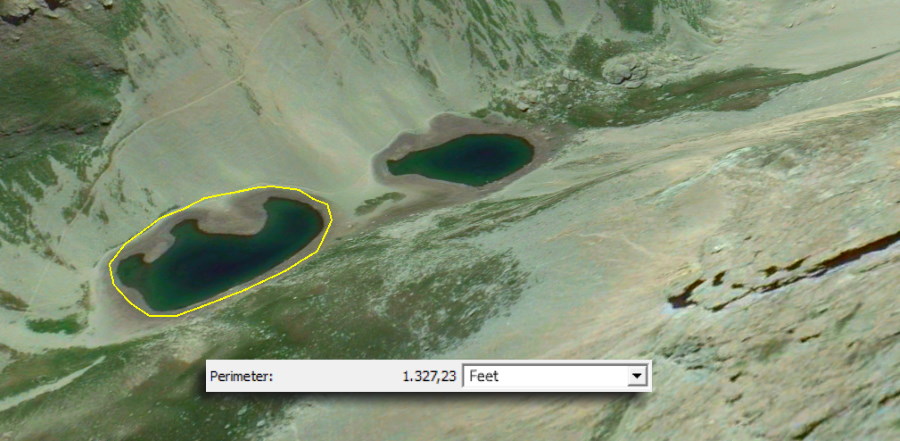

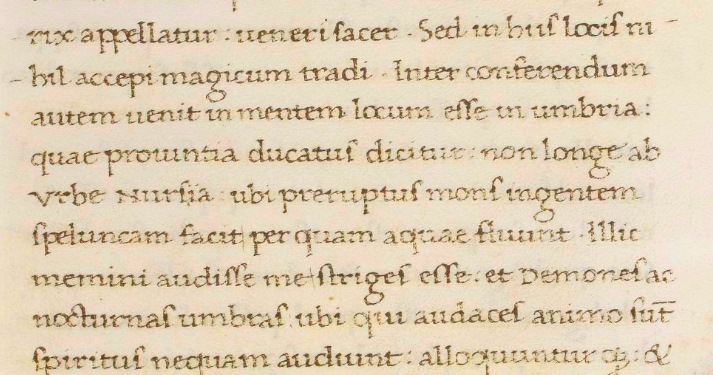

Here they are, in a beautiful satellite picture taken in July, 2017. They are small and powerless and vulnerable. They are only a pale ghost of what the Lake used to be in past centuries. And they are fading away (Fig. 2).

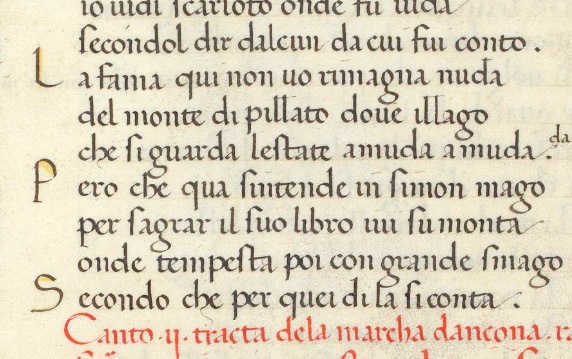

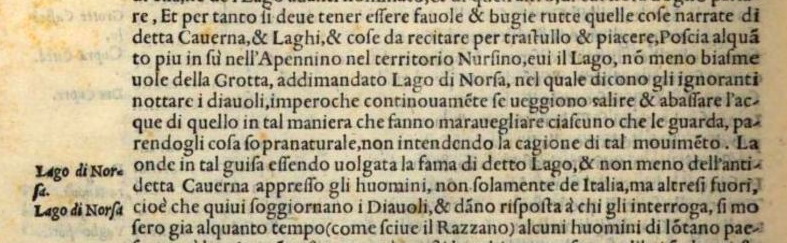

Yet their pure, utterly clear waters are still shimmering with billions of sparks of light. Their history seems to shine through their present fragility. Their legend - its legend, of a Lake concealed within the remote peaks of the Apennines, in central Italy, has been talking to people for centuries across all nations of Europe. Its mystery still resounds, in our present days, in our fascinated ears, when we still read the ancient, blood-curdling tales of the necromantic waters which house demons and raise tempests, as we strive to bring to light the enigma which lies under its liquid, crystal-like surface, the way we did in a previous, groundbreaking research paper ("Sibillini Mountain Range, the chthonian legend") (Fig. 3).

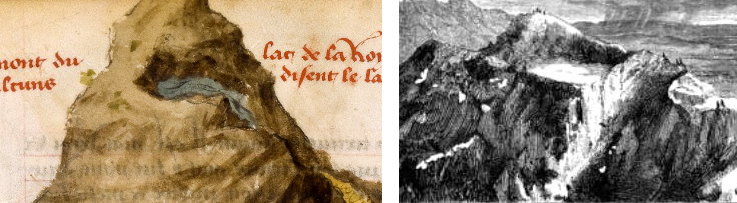

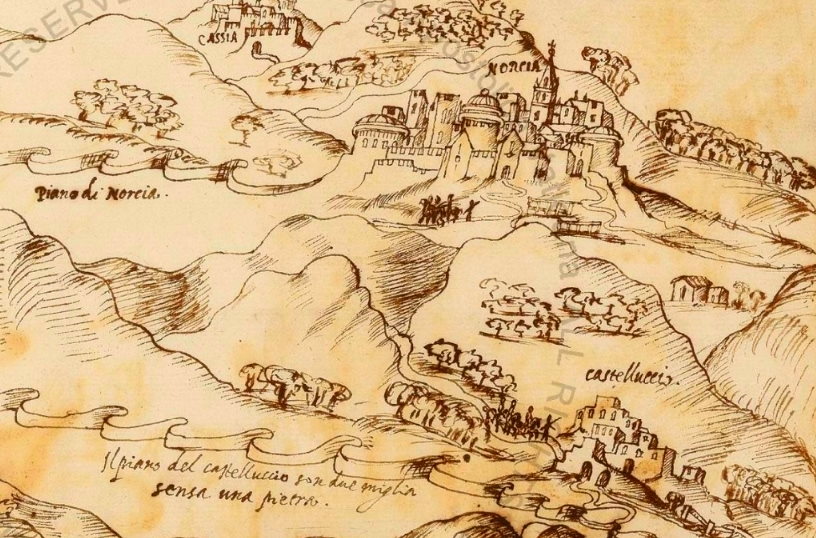

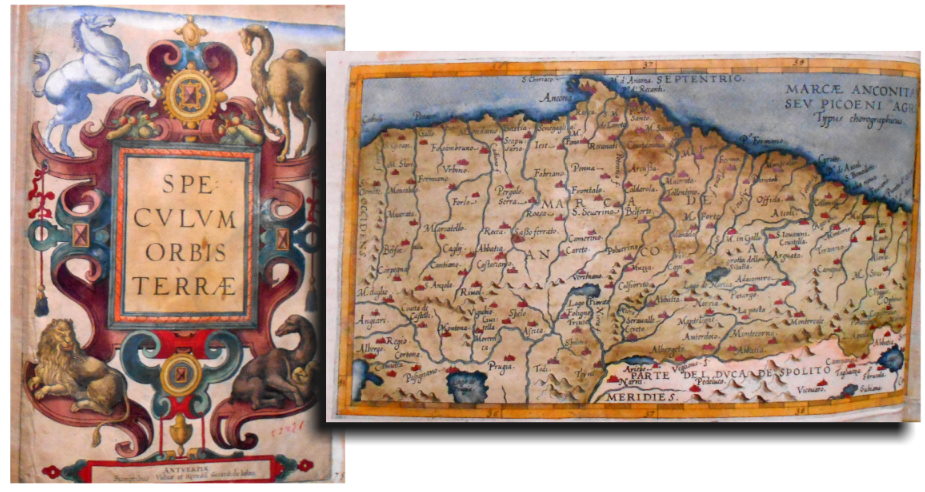

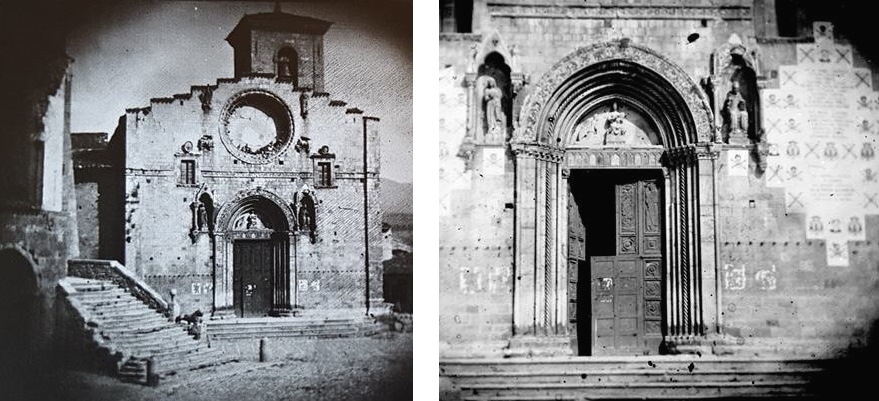

And we want to see it, the Lake, for a last time, the way it was in the ripeness of the early centuries during which visitors flocked by its shore and mentions flowed through manuscripts and printed books.

Here is the Lake of Pilate, as Antoine de la Sale saw it, six hundred years ago. A sinister, single, impressive Lake, fully deserving its dedication to a key figure of the Gospels, Pontius Pilate. A Lake of mystery. A Lake of dream (Fig. 4).

The Lake of Pilate may be dying. But its legendary fascination will live on forever.

Ponzio Pilato e la forma delle acque /23. La leggenda vive ancora

Ponzio Pilato e i Monti Sibillini, nella catena degli Appennini. Un Lago negromantico dedicato al nome di un prefetto romano vissuto nel primo secolo, il funzionario imperiale che condannò Gesù Cristo alla morte. Un bacino ricolmo di acque oscure, circondato dagli spaventosi precipizi del Monte Vettore: uno spazio solitario e sinistro che un tempo ospitava un ghiacciaio situato proprio tra i Monti Sibillini, e svanito migliaia di anni orsono.

Nel presente studio, abbiamo cavalcato attraverso i secoli, in cerca della forma del Lago di Pilato: un Lago, due Laghi e, infine, nessun Lago.

Un lungo viaggio, che ci ha condotto dal sinistro Lago dei secoli passati fino ai Laghi depauperati e sofferenti del nostro tempo presente, e alla loro prevedibile, imminente estinzione in un futuro che è distante da noi quanto lo è il mutamento climatico globale.

Abbiamo iniziato il nostro itinerario partendo dal quattordicesimo secolo, con Petrus Berchorius e le sue inquietanti parole: «tra le montagne che si innalzano in prossimità di questa città [Norcia] si trova un lago, dagli antichi consacrato ai dèmoni, e da questi visibilmente abitato...». Ci siamo poi uniti al gentiluomo francese Antoine de la Sale nella sua visita, effettuata nell'anno 1420, al Lago il cui nome è dedicato a Pilato e alla Sibilla (Fig. 1). Da allora in poi, le descrizioni e i riferimenti a proposito di un sinistro Lago nascosto tra le montagne della Sibilla, nell'Italia centrale, si sono susseguiti l'uno dopo l'altro, attraverso i secoli quindicesimo, sedicesimo e diciassettesimo.

Papa Pio II Piccolomini, Flavio Biondo, Arnold von Harff, Leandro Alberti menzionano quel Lago oscuro situato tra le dirupate vette delle montagne della Sibilla. Un singolo, impressionante Lago, così come ritratto in diverse mappe geografiche nel corso dei secoli: il sembiante di quelle acque è dipinto sulle pareti della celebre Galleria delle Carte Geografiche presso i Musei Vaticani in Roma; Giuseppe Moleti, nella sua edizione della "Geografia" di Tolomeo disegna un singolo Lago, e una versione oblunga di esso viene presentata da Gerard de Jode nel suo "Speculum Orbis Terrae"; lo specchio d'acqua fa anche capolino nella mappa elaborata da Giubilio e Maggi nel 1592, apparendo poi nell'"Atlas sive Cosmographicae Meditationes de fabrica mundi et fabricati figura" di Gerardus Mercator, nell'"Italia descritta in generale" di Giovanni Antonio Magini, nell'"Italia Antiqua" di Philipp Clüver, e nella "Nova et accuratissima totius terrarum orbis tabula" di Joan Blaeu.

In tutti i citati riferimenti letterari e cartografici, il Lago di Pilato è sempre uno: un singolo, impressionante Lago, occultato tra le braccia di roccia del Monte Vettore. Solamente una testimonianza, nel corso del sedicesimo secolo, ci fornisce una visione differente: due Laghi separati e scarsamente alimentati, come attestato nel manoscritto Vat. Lat. 5241, contenente il resoconto di una visita effettuata forse duranta un'estate calda e asciutta. Ma questa testimonianza rimarrà sepolta per secoli, nascosta tra i numerosi fogli di pergamena che raccoglievano una collezione di antiche iscrizioni latine: una testimonianza che fu riscoperta e riportata nuovamente alla luce solamente nel 1982.

E così, negli scorsi secoli, la forma ordinaria del Lago di Pilato era quella di un singolo bacino, con temporanee perdite d'acqua nella stagione estiva in grado di condurre il Lago verso una partizione caratterizzata dalla presenza di due Laghi più piccoli. Nondimeno, la sua fama attraversava l'Europa nella forma di un singolo Lago: era uno, ed era negromantico, ed era leggendario.

Quando abbiamo raggiunto i secoli diciassettesimo e diciottesimo, non abbiamo rinvenuto nulla di nuovo rispetto al passato: il Lago era ancora rappresentato come un singolo specchio d'acqua, stabilmente fedele alla propria unicità, come possiamo reperire in ulteriori mappe edite da Silvestro Amanzio Moroncelli e Guillaume de L'Isle. Abbiamo anche potuto ripercorrere i passi di due grandi cartografi gesuiti, Christopher Maire e Ruggero Giuseppe Boscovich, con il loro difficile e avventuroso passaggio attraverso i Monti Sibillini: essi non videro il Lago di Pilato, e dunque il bacino appare essere totalmente assente dalla loro dettagliata mappa dello Stato Ecclesiastico. E ci siamo imbattuti in un'ulteriore, isolata descrizione dei Laghi nella loro carente forma estiva: è contenuta nelle "Istorie dell'antica città di Norsia" di Padre Fortunato Ciucci, il quale scrisse che essi apparivano in «forma d'occhiale», aggiungendo che «ho visto, e considerato da molti segni che si riduchino insieme e faccino un sol lago; ma l'Estate mancandoli il corso dell'acqua vengono a separarsi, come si vedono in forma d'occhiali». Ma questo testo non ebbe alcuna circolazione: ne esistono infatti solamente quattro copie manoscritte, ed esse non furono mai stampate in volume, se non in una moderna edizione pubblicata nel 2003.

È nel corso del diciannovesimo secolo che un cambiamento, tra i Monti Sibillini, inizia a manifestarsi. Malgrado ciò, nessuna modificazione pare essere visibile quando un geografo dell'Imperiale e Regio Istituto Geografico Militare austriaco traccia una bellissima mappa della Toscana e dello Stato Pontificio: tra il 1841 e il 1843, il Lago si mostra ancora, agli occhi professionali di Giovanni Marieni, come un singolo bacino, e in tal modo viene riportato nel relativo foglio cartografico.

La seconda metà del secolo introduce una nuova forma per il Lago. Inizialmente, nulla sembra essere mutato: nella stagione estiva, il Lago si presenta suddivisio in due specchi d'acqua più piccoli, così come era accaduto anche nei secoli precedenti. Possiamo leggere dell'aspetto del Lago nella relazione scritta, nell'estate del 1877, dal Conte Girolamo Orsi, un illustre membro del Club Alpino Italiano, all'epoca di recente fondazione: «fra queste [due parti del Monte Vettore], in fondo agli enormi precipizi, sono i Laghi di Pilato», egli scrive, «i Laghi di Pilato, e le loro acque sì intensamente azzurre, e l'orrido burrone che lì vicino sprofonda». E, nel 1887, anche Giovanni Battista Miliani può osservare i due Laghi estivi: «in fondo a valle, a sinistra, si scorge il Lago di Pilato, che in estate, come quando lo vidi io, ha forma di occhiali».

E si verificano anche occasioni in cui il Lago ritorna ancora alla sua forma originaria e impressionante, un singolo specchio d'acqua. Quando i soci del Club Alpino Italiano visitarono il Monte Vettore nel 1879, essi poterono contemplare l'antica visione già descritta da Antoine de la Sale più di quattrocento anni prima: un grande, singolo Lago, minacciosamente annidato tra le creste arcuate della montagna, nel modo in cui esso si presenta nel disegno pubblicato all'epoca da "L'Illustrazione Italiana". Una visione confermata anche da un altro resoconto, vergato in modo indipendente dalla Contessa Lucia Rossi Scotti, la quale si era unita agli alpinisti nella loro ascesa di quel giorno: «... L'oscuro verde Lago di Pilato formatosi fra quelle gole per il disgelamento dei ghiacci...».

Ma alla fine del diciannovesimo secolo arriverà il tempo, per il Lago di Pilato, di esperimentare una trasformazione. Per qualche ragione, nevi e piogge parrebbero non essere più in grado di riempirlo fino alla forma di singolo bacino. Da quel momento in poi, il Lago di Pilato inizierà a trasformarsi, in modo sempre più marcato, nei due Laghi di Pilato che conosciamo oggi.

La più accurata descrizione del nuovo aspetto tipico del nostro leggendario bacino è delineata dal filologo italiano Pio Rajna nel 1897: «Il lago mi si è presentato diviso in due specchi elittici [...] Il paragone con un par d'occhiali [...] è realmente grafico». Un'occorrenza usuale, in estate. Ma in quella specifica estate la neve non mancava affatto, accumulata sui versanti del circo glaciale del Monte Vettore, pur non essendo palesemente in grado di conferire al Lago la sua forma unica ed estesa:

«Ho trovato neve in discreta quantità dattorno al lago: e per solito il Vettore non si priva mai, come dice Antonio, di questo ornamento. A Foce mi si è detto tuttavia esserci stato un periodo di nove anni, finito da un ventennio, in cui neve non s'ebbe neppure in inverno».

Era forse accaduto qualcosa, al Lago di Pilato? Secondo Rajna, «il lago non è più ora ciò che fu un tempo»: circa quaranta anni prima «esso ruppe le dighe naturali della sua fronte, le quali non si sono più riformate. Antoine de la Sale lo vide dunque notevolmente diverso d'aspetto e più profondo». E, in effetti, nel 1859 un grande terremoto aveva colpito la regione di Norcia: era stata forse questa la causa del drammatico collasso della porzione settentrionale del bacino glaciale che ospita il Lago negromantico? Erano state le onde sismiche a mutare l'aspetto del bacino per sempre, con l'impossibilità di un ritorno alla forma singola seppure in presenza di neve?

Come abbiamo avuto modo di illustrare nel presente articolo di ricerca, non siamo stati in grado di accertarlo. Il terremoto del 1859 fu certamente abbastanza intenso da ridurre Norcia a un cumulo di rovine; eppure, la sua magnitudo e il suo epicentro non sembrano essere stati marcati dalla potenza e dalle caratteristiche necessarie per potere agire sul Monte Vettore in modo così drammatico, e nessun resoconto che sia relativo a un tale ipotetico evento è stato mai reperito, fino ad oggi, negli archivi locali. Inoltre, se veramente un evento del genere fosse mai accaduto, i membri del Club Alpino Italiano non avrebbero potuto esperimentare la visione di un Lago singolo in un'epoca così tarda come risulterebbe essere il 1879, e come invece riporta una rivista illustrata di quegli anni.

In ogni caso, malgrado il manifestarsi occasionale di quelle acque in qualità di singolo bacino, a partire dalla seconda metà del diciannovesimo secolo la forma del Lago di Pilato sarà destinata a percorrere un sentiero che conduce verso una crescente duplicazione e un incremento nella carenza di acqua: il Lago comincerà a presentarsi come un bacino sostanzialmente suddiviso in due Laghi più piccoli, sia totalmente separati che uniti da una stretta striscia d'acqua. Sia in estate che in inverno. Perché, durante l'inverno, esso non riuscirà più a riguadagnare la propria forma singola e originaria. Un segnale della crescente scarsità di precipitazioni nevose e piovose, e forse di possibili variazioni nella configurazione fisica del bacino roccioso.

La cartografia tardo-ottocentesca tracciata dall'Istituto Geografico Militare mostra un lago allungato ora visibilmente intaccato al centro, pronto a separarsi in due distinti specchi d'acqua. La stessa indentazione sarà rappresentata da Cesare Lippi-Boncambi nel proprio diagramma risalente al 1947. E benché ulteriori mappe militari pubblicate nel 1952 presentino il Lago nella sua forma più florida, seppure assai allungata, la realtà effettiva era significativamente diversa: vecchie cartoline postale e fotografie aeree non possono che certificare come il Lago di Pilato abbia già mutato la propria forma distribuendosi su due bacini più piccoli, colpiti in modo crescente da una evidente carenza idrica, nonché forse soffocati da ingenti masse di detriti in continua caduta dalle creste circostanti.

Duplicazione, esaurimento e insufficiente alimentazione idrica. Una condizione che sarà ripetutamente osservata nel corso dei primi decenni del ventunesimo secolo. Le immagini dei Laghi, tristemente ridotti a due piccoli stagni, e le testimonianze fotografiche relative a una valle glaciale completamente svuotata di ogni traccia di acqua, così come accaduto nel 2017 e nel 2020, non possono che spezzare il cuore.

Nel presente articolo, abbiamo riepilogato le possibili ragioni che potrebbero trovarsi all'origine di un depauperamento così critico. Non abbiamo potuto fornire una conferma di quanto sostenuto da Pio Rajna in merito al collasso della barriera settentrionale del bacino che ospita il Lago, un collasso che sarebbe avvenuto alla metà del diciannovesimo secolo. Abbiamo ripercorso le varie posizioni espresse dai ricercatori in relazione al possibile svuotamento della acque attraverso il fondo del bacino e verso il sottostante strato di calcare massiccio, a causa di nuove fessurazioni potenzialmente prodottesi nel suolo a seguito dei terremoti del 2016; ma accurate investigazioni non hanno evidenziaro la sussistenza di un tale processo di svuotamento presso il sito del Lago.

Abbiamo allora identificato due effetti principali, entrambi di natura avversa, che stanno agendo sulle condizioni di salute e sulla forma complessiva dei Laghi di Pilato. Due effetti negativi che stanno gradualmente conducendo il bacino montano verso una conclusione fatale e inesorabile.

Una prima causa, assai critica, per il crescente depauperamento dei Laghi di Pilato è il cambiamento climatico. Ed è sufficiente questa affermazione per far risuonare nelle nostre orecchie una sentenza di morte.

A partire dal quattordicesimo secolo e fino alla metà del diciannovesimo, la Piccola Era Glaciale, una condizione climatica che ha avuto effetti sull'Europa ed è stata caratterizzata da temperature moderatamente più basse rispetto ai precedenti periodi temporali, ha assicurato un'alimentazione idrica ottimale al Lago di Pilato: gli inverni sono stati più freddi, le nevicate più intense, abbondanti accumuli di neve sono stati presenti nei Monti Sibillini, e piogge copiose hanno sostenuto il Lago preservandone il bilancio delle acque.

Per questo, durante molti secoli, e come testimoniato dalle molte fonti da noi investigate nel presente articolo, il Lago di Pilato era un singolo, impressionante, negromantico bacino montano ben alimentato, e segnato da depauperamenti solamente temporanei che influivano sulla forma del Lago durante la buona stagione.

Poi, il clima iniziò a mutare.

Gli effetti dei cambiamenti indotti dall'uomo cominciarono a manifestarsi a partire dalla metà del diciannovesimo secolo, con un rapido incremento delle temperature globali. E gli Appennini italiani, come il resto del continente europeo, ne subirono parimenti le conseguenze.

Il Lago di Pilato iniziò a cambiare: il processo di trasformazione in due Laghi separati ebbe un carattere graduale, con nevicate statisticamente sempre meno intense, e piogge analogamente in lenta riduzione.

Nell'agosto del 1876, il Conte Girolamo Orsi poté osservare, all'interno del circo glaciale del Monte Vettore, «i Laghi di Pilato, alimentati da quella estesa lente di ghiaccio, embrione di un ghiacciaio perenne, che laggiù si nasconde ai raggi del sole. [...] Quelle nevi perpetue interposte ai tre culmini, là in quella gola nord-est del Petrara, che danno alimento a quei, laghi».

E Giovanni Battista Miliani, nel 1886, scrisse che «in tutta questa valle [dove giacciono i Laghi], nei luoghi più riparati dal sole, esistono depositi di neve, che assai di rado sgelano completamente in estate».

Oggi, quelle nevi perenni non esistono più, totalmente cancellate dall'ardore del calore estivo generato dal riscaldamento globale: lo stesso fenomeno di riscaldamento che sta uccidendo i ghiacciai in molte aree del mondo.

Un processo che iniziò ad essere rilevabile alla fine del diciannovesimo secolo, come riferito da Pio Rajna nei propri scritti:

«Ho trovato neve in discreta quantità dattorno al lago: e per solito il Vettore non si priva mai, come dice Antonio, di questo ornamento. A Foce mi si è detto tuttavia esserci stato un periodo di nove anni, finito da un ventennio, in cui neve non s'ebbe neppure in inverno».

Così il Lago cominciò a presentare una sorta di indentazione, e poi si suddivise, facendo apparire due Laghi distinti: non solo nelle estati aride, ma durante tutto il corso dell'anno, e tutti gli anni. E, mentre il riscaldamento globale continuava a crescere, le nevi e le piogge non furono più in grado di sostenere le necessità idriche del bacino, in presenza di scarsa alimentazione e periodi di intensa siccità.

I risultati di questo nefasto fenomeno sono svuotamento e inaridimento.

Purtroppo, però, non è questo il solo effetto negativo che sta oggi agendo sui Laghi di Pilato, conducendoli nella direzione di un'irrevocabile estinzione. Perché una seconda causa, assai critica anch'essa, è costituita dagli smottamenti.

Come artigli mortali, due grandi smottamenti storici incombono sui Laghi di Pilato dai versanti orientale e occidentale del circo glaciale del Monte Vettore. Per secoli e secoli essi hanno scagliato massi, pietre e detriti dalle alte vette circostanti direttamente nelle acque sottostanti. E la frana orientale, in particolare, ha edificato, a mano a mano, una cresta centrale, che divide il lago originale in due differenti bacini.

E così il fondo degli specchi d'acqua si è innalzato sempre di più, attraverso molti secoli e molteplici terremoti, i quali hanno certamente contribuito all'accelerazione di questo lungo, storico, ininterrotto processo di riempimento. Un processo che ha esperimentato forse una qualche sorta di avanzamento tra il 1879 e il 1897: dalla visione di un florido Lago così come contemplato dai soci del CAI ai due Laghi completamente separati osservati da Pio Rajna, malgrado la presenza di neve in scioglimento.

Smottamenti e innalzamento del fondo. Cambiamento climatico e depauperamento idrico. Effetti avversi che strangolano e soffocano il bacino posto tra le creste del Monte Vettore.

Ecco perché siamo ora di fronte alla morte imminente, finale e irrevocabile, dei Laghi di Pilato.

In tutta evidenza, il Lago di Pilato dei secoli passati, nella sua forma singola e illustre così come fu celebrata per molte centinaia di anni in tutta Europa, non esiste più. E non potrà tornare mai più.

E il Lago come noi lo conosciamo oggi, nella sua forma minore, composta da due Laghi più piccoli e separati, sta morendo.

Eccoli qui, in una splendida immagine satellitare acquisita nel luglio 2017. Sono piccoli e indifesi e vulnerabili. Essi sono solo un pallido fantasma di ciò che il Lago era solito essere negli scorsi secoli. E stanno lentamente svanendo (Fig. 2).

Eppure le loro acque così pure, così completamente trasparenti scintillano ancora di milioni di faville di luce. La loro storia pare brillare attraverso la loro attuale fragilità. La loro leggenda - la sua leggenda, quella di un Lago nascosto tra i remoti picchi degli Appennini, al centro dell'Italia, ha parlato agli uomini per secoli attraversando tutte le nazioni d'Europa. Il suo mistero risuona ancora, ai nostri giorni, alle nostre orecchie affascinate, quando ci troviamo a rileggere gli antichi, spaventosi racconti a proposito delle acque negromantiche che ospitavano demoni e suscitavano tempeste, mentre tentiamo di portare alla luce l'enigma che giace al di sotto della sua superficie liquida e cristallina, così come abbiamo cercato di fare in un nostro precedente, straordinario articolo ("Monti Sibillini, la leggenda ctonia") (Fig. 3).

E noi vogliamo contemplarlo, quel Lago, per un'ultima volta, nel modo in cui esso si presentava nella piena maturità di quei secoli durante i quali i visitatori si affollavano presso le sue rive e le menzioni fiorivano nei manoscritti e nei volumi a stampa.

Eccolo, il Lago di Pilato, come Antoine de la Sale poté osservarlo, seicento anni fa. Un Lago sinistro, singolo, impressionante, che meritava pienamente la propria dedicazione nei confronti di una figura chiave dei Vangeli, Ponzio Pilato. Un Lago di mistero. Un Lago di sogno (Fig. 4).

Il Lago di Pilato sta forse morendo. Ma il suo fascino leggendario non potrà che vivere per sempre.

31 Dec 2020

Pontius Pilate and the shape of the waters /22. Landslides: when the mountain swallows its siblings

Climate change is certainly leading the Lakes of Pilate, once a single, impressive Lake, towards extinction. An extinction which is basically to be considered as a side effect of a much larger, global-scale process that is putting at risk huge geographical features all around the world, including glaciers in the Alps.

However, we strongly repute that possibly this is not the one and only effect, of a nasty nature, which has been unfavourably affecting the life of the Lake of Pilate across the last one hundred fifty years.

Another physical effect, on a local scale, may have significantly influenced the shape of the water basin set amid the cliffs of Mount Vettore. An additional effect which, when combined with the decrease in snowfalls and rainfalls due to climate change, is equivalent to a mortal blow inflicted to our legendary Lake: a stifling grip around its neck, leading to utter suffocation.

And this grip is landslides.

As we already noted in a previous paragraph, the whole area of the Sibillini Mountain Range is subject to recurrent earthquakes and violent seasonal storms. And Mount Vettore's glacial cirque is at the core of all this.

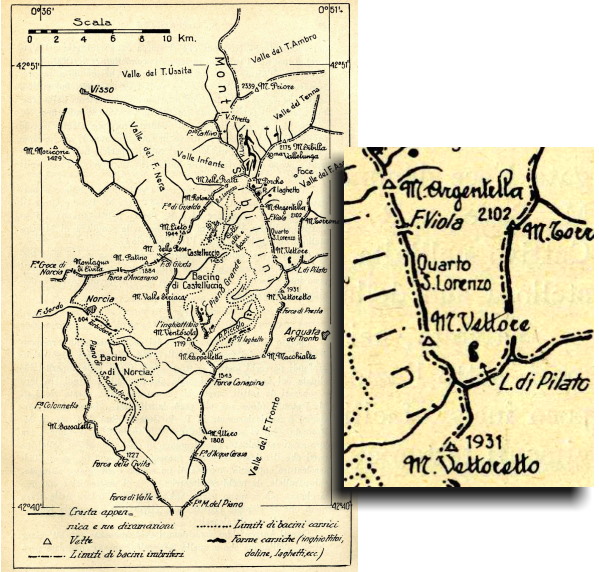

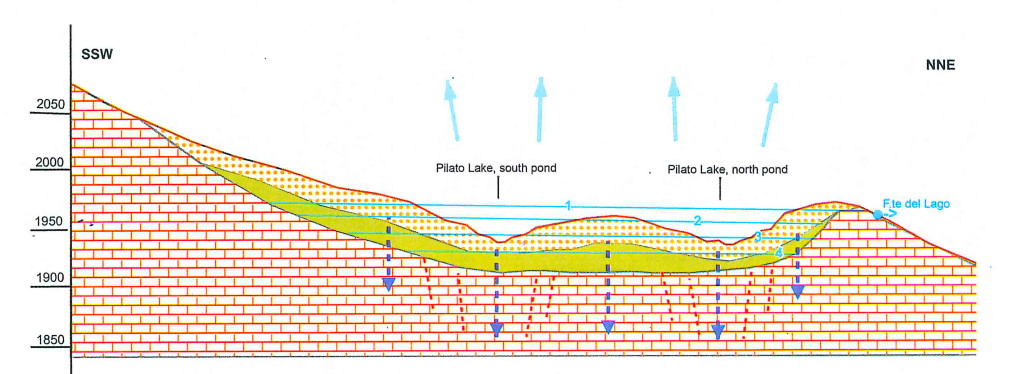

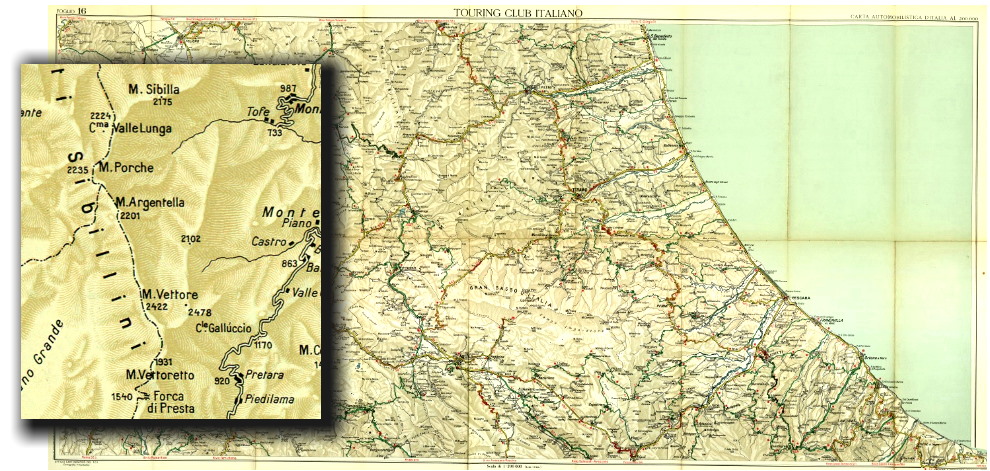

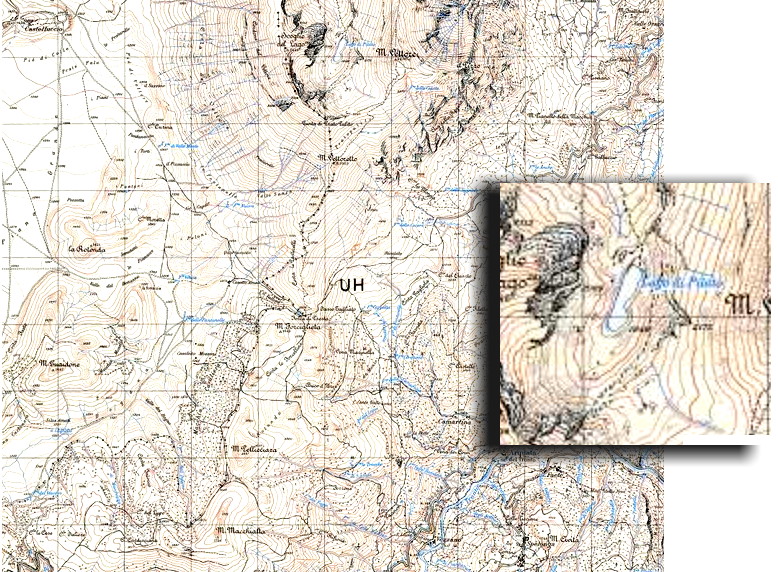

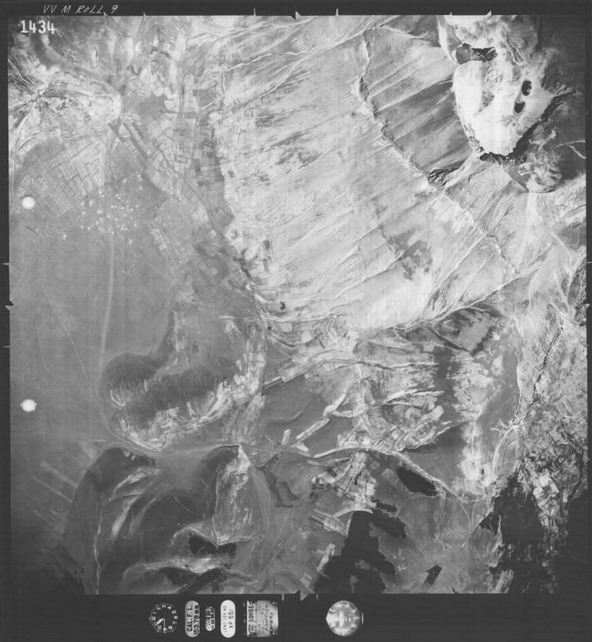

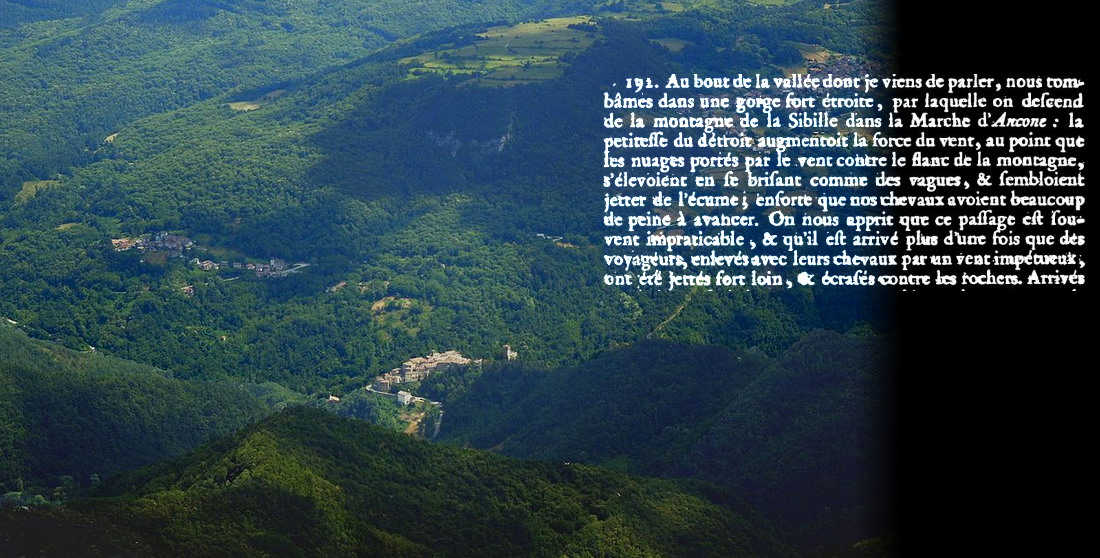

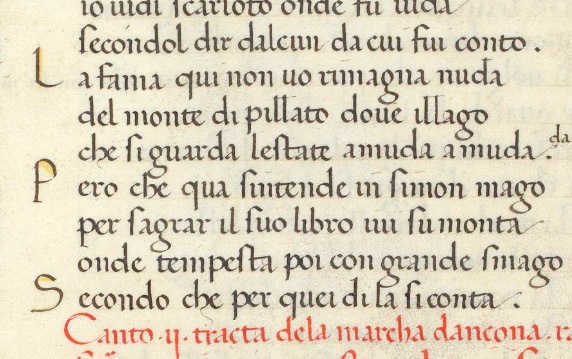

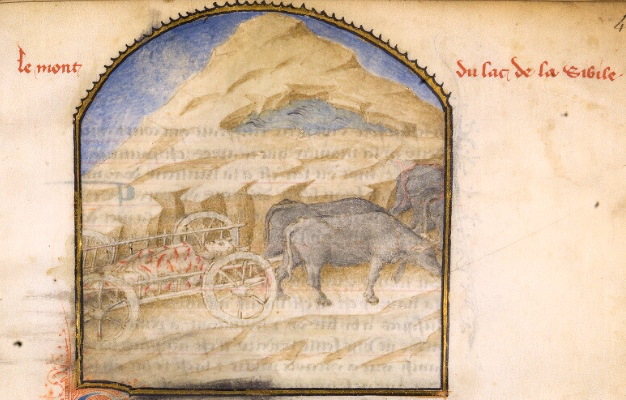

The very shape and nature of the rocky cradle that once housed a glacier render the site prone to landslides from the overhanging cliffs which encircle the whole arched space. The rock is fractured and grinded by the action of the now-vanished ice mass. Debris and rubble cover the bottom of the cirque. Earthquakes and storms continue to effect an uninterrupted strain on the titanic walls of sheer stone, from which pebbles and rocks and boulders, across the decades and centuries, keep on sliding and falling onto the Lake (Fig. 1).

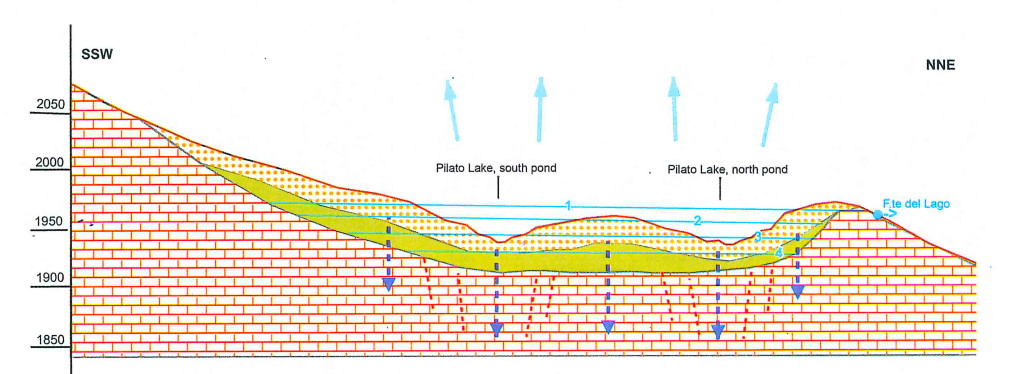

This ceaseless process has induced a progressive raise in the elevation of the Lake's bottom, thus leaving less volume available to the water content of the basin, and creating a growing barrier of debris at the middle of the glacial cirque, which eventually caused the partition of the Lake, in earlier times a single basin, into two ordinarily separated ponds.

So, in the past the glacial cirque was markedly deeper, allowing for more water; across the centuries, the site's bottom slowly raised, and less water can be accommodated within the cirque without overflowing from the northern side into the underlying valley. Gilberto Pambianchi, a geologist at the University of Camerino, claimed that the process was accelerated by the great seismic sequence which occurred in 2016: according to his estimate, the landslides which followed the earthquakes precipitated stones and debris right into the Lakes, with a rise of the bottom's elevation of about three feet, though this figure has not yet been confirmed nor reported in scientific papers.

However, we are interested in less recent landslides. Are there any of them which are visible around the glacial cirque that houses the Lakes of Pilate?

Yes. Ancient, historical landslides are there.

A first one is found on the western side of the rounded glacial valley: a funnel-shaped mass of debris coming down from a vertex set up above, below the peaks of Cima del Redentore and Pizzo del Diavolo. This large quantity of rubble keeps on rolling and falling into the smaller, southernmost pond, which appears to be almost overwhelmed by the neverending accumulation of stones (Fig. 2).

But it is the second landslide that possibly sealed the destiny of the larger Lake of Pilate as it was known in the past.

This further landslide is set on the opposite, eastern side of the glacial cirque of Mount Vettore. And it is impressive altogether.

It originates from the mountainside which goes up to the most elevated peak of the whole mount, once called the Petrara peak. A sort of wound, a veritable scar marks this portion of the cliff: from it, as if it were a spring of fresh mountain water, rocks and debris seem to pour out and sprinkle onto the underlying Lakes (Fig. 3).

Such copious flow of stones and pebbles is hurled right onto the low ridge that separates the two ponds. Actually, it makes up and feeds that ridge.

This is the landslide that gave rise to the two Lakes: from a single Lake to a dual configuration, increasingly parted by an ever-growing mass of rocks ceaselessly falling into the waters from the eastern side of the glacial cirque.

It is manifestly clear that centuries and centuries of slowly-flowing landslides, fuelled and accelerated on specific occasions by earthquakes, storms and temperature variations, gradually filled up the bottom of the Lake's basin. A simultaneous, claw-shaped flank attack conducted on both sides, the eastern and the western, of the original Lake.

In the long term, a deadly attack.

When the bottom of the basin will be filled with enough rubble so as to reach the elevation of the front dike to the northern side of the basin (6,463 feet, as reported in a previous chapter in this same research paper), the Lake or Lakes will not be able to form anymore: water will just leave the glacial cirque unhindered by flowing straight down into the valley underneath.

Across the centuries, the Lake's bottom has raised and raised up to the present level (6365 feet): still a gap of some 100 feet needs to be filled before the waters reach the northern dike's level. The landslides have still much work to do to achieve the utter eradication of the Lakes of Pilate. Mount Vettore is quietly, relentlessly swallowing up its own siblings, nested between its rocky arms (Fig. 4).

And yet the landslides are working nicely and steadily, with sudden accelerations due to earthquakes. They already succeeded in parting the Lake into two smaller Lakes, by building up a sort of ridge between the northern and southern basins.

Did this loading process experience some sort of boost at the middle of the nineteenth century? We actually don't know, because a geological investigation is needed if we intend to ascertain the age of the most significant flows of rubbles which are present within the two landslides. As a matter of fact, it was in 1879 that the aristocratic members of the Italian Alpine Clube saw the Lake in its healthy, single form for the last time; and it was in 1897, at the end of the nineteenth century, that Pio Rajna beheld the two Lakes fully separated by a portion of dry land, even though accumulated snow was all around: a sign that the central ridge was becoming high enough to ensure a successful partition of the two Lakes despite snowfalls and rainfalls.

A deadly attack, as we stated earlier in this chapter. But the more deadly it appears to be, when we come to consider the concurrent action of climate change and global warming.

Less snow. Less rain. Less space available to accommodate water. A relentless process, which is going ahead and ahead.

Until the Lakes of Pilate will eventually die.

Ponzio Pilato e la forma delle acque /22. Smottamenti: quando la montagna divora la propria progenie

Il cambiamento climatico sta certamente conducendo i Laghi di Pilato, un tempo un singolo e impressionante Lago, verso l'estinzione. Un'estinzione che deve essere fondamentalmente considerata come un effetto collaterale di un processo assai più vasto, e su scala globale, che sta ponendo a rischio grandi elementi geografici in tutto il mondo, inclusi i ghiacciai alpini.

Nondimeno, riteniamo convintamente che forse non sia questo il solo e unico effetto, di natura sfavorevole, che stia producendo effetti negativi sulla vita del Lago di Pilato nel corso degli ultimi centocinquanta anni.

Un altro effetto fisico, su scala locale, potrebbe avere significativamente influenzato la forma dello specchio d'acqua circondato dalle creste del Monte Vettore. Un effetto ulteriore che, se combinato con la rilevata diminuzione nelle precipitazioni nevose e nelle piogge connessa al cambiamento climatico, equivale a un colpo mortale inflitto al nostro leggendario Lago: una sorta di presa soffocante attorno al collo, in grado di condurre alla totale asfissia.

E questa presa mortale è costituita dagli smottamenti.

Come da noi già notato in un precedente paragrafo, l'intera area dei Monti Sibillini è soggetta a ricorrenti terremoti e violente tempeste stagionali. E il circo glaciale del Monte Vettore si trova proprio nel cuore di tutto questo.

La forma e la natura stessa della culla di roccia che un tempo ospitava un ghiacciaio rende il sito soggetto a frane in caduta dalle incombenti pareti che circondano l'intero spazio arcuato. La roccia risulta essere fratturata e triturata dall'azione della massa di ghiaccio oggi svanita. Pietre e detriti ricoprono il fondo del circo glaciale. Tempeste e terremoti continuano a esercitare un'ininterrotta pressione sulle mura titaniche di roccia verticale, dalle quali ghiaia, pietre e grandi massi, attraverso i decenni e i secoli, continuano a scivolare e a cadere nel Lago (Fig. 1).

Questo incessante processo ha prodotto un progressivo innalzamento nell'altitudine del fondo del Lago, lasciando così un volume descrescente a disposizione del contenuto in acqua del bacino, e creando una crescente barriera di detriti al centro del circo glaciale, una barriera che ha causato infine la partizione del Lago, un tempo un singolo bacino, in due specchi d'acqua usualmente separati.

Così, in passato il circo glaciale risultava essere significativamente più profondo, e in grado di accogliere maggiori quantità d'acqua; nel corso dei secoli, il fondo del sito si è lentamente innalzato, in modo tale da rendere possibile l'accoglimento di un volume d'acqua minore senza che si vada a verificare una tracimazione attraverso il lato settentrionale verso la vallata sottostante. Gilberto Pambianchi, un geologo dell'Università di Camerino, ha sostenuto che tale processo sia stato accelerato dalla grande sequenza sismica occorsa nel 2016: secondo la sua stima, le frane che avrebbero seguito le scosse avrebbero precipitato pietre e detriti direttamente nei Laghi, con un innalzamento del fondo pari a circa un metro, benché tale valutazione non sia stata ancora confermata né riportata in specifici articoli scientifici.

In ogni caso, il nostro interesse si concentra maggiormente su smottamenti storici e dunque meno recenti. Ve ne sono forse alcuni le cui tracce siano ancora visibili all'interno del circo glaciale che ospita i Laghi di Pilato?

Sì. Le frane storiche, antiche sono lì.

La prima è osservabile sul lato occidentale della vallata glaciale semicircolare: una massa di detriti a forma di imbuto, discendente da un vertice situato in alto, al di sotto dei picchi della Cima del Redentore e del Pizzo del Diavolo. Questa grande quantità di ghiaia e pietre continua a rotolare e a cadere nel più piccolo Lago meridionale, che appare essere quasi sopraffatto dall'instancabile accumulo di rocce (Fig. 2).

Ma è la seconda frana ad avere forse segnato il destino del grande Lago di Pilato così come esso era conosciuto in passato.

Questo ulteriore smottamento è collocato sul lato opposto, quello orientale, del circo glaciale del Monte Vettore. Ed è assolutamente impressionante.

Esso trova origine nel fianco della montagna che sale fino alle vetta più elevata dell'intero monte, un tempo chiamata Cima Petrara. Una sorta di ferita, una vera cicatrice segna questa porzione della parete: da essa, come se fosse una sorgente di fresca acqua di montagna, pietre e detriti sembrano sgorgare e quasi sprizzare nei due Laghi sottostanti (Fig. 3).

Questo copioso flusso di rocce e ghiaia è scagliato direttamente sulla bassa cresta che separa i due bacini. In effetti, è proprio questo flusso a generare e alimentare quella cresta.

È questa la frana che dette origine ai due Laghi: da un singolo Lago a una configurazione duplice, ripartita in modo sempre più netto da una crescente massa di rocce che ininterrottamente discendono nelle acque dal lato orientale del circo glaciale.

È dunque chiaro come secoli e secoli di smottamenti in lento movimento, alimentati e accelerati in specifiche occasioni da terremoti, tempeste e variazioni di temperatura, abbiano gradualmente riempito il fondo del bacino che ospita il Lago. Un attacco simultaneo, accerchiante, condotto da ambo i lati nei confronti del Lago originale: una sorta di tenaglia, che agisce sia dal lato orientale che da quello occidentale.

Nel lungo termine, un attacco mortale.

Quando il fondo del bacino sarà riempito con una quantità di detriti sufficiente a raggiungere l'altezza della diga frontale posta sul lato settentrionale del bacino stesso (1.970 metri, come illustrammo in un precedente capitolo di questa stessa ricerca), il Lago o i Laghi non saranno più in grado di formarsi: l'acqua abbandonerà semplicemente il circo glaciale senza più costrizioni, fluendo direttamente giù nella vallata sottostante.

Nel corso dei secoli, il fondo del Lago si è innalzato ininterrottamente, fino a raggiungere il livello attuale (1940 metri): un divario di circa 30 metri deve essere ancora colmato prima che le acque raggiungano il livello del fronte settentrionale. Le frane hanno ancora molto lavoro da fare prima di ottenere il risultato di una totale eradicazione dei Laghi di Pilato. Il Monte Vettore sta divorando, lentamente, silenziosamente, la propria stessa progenie, nascosta tra le sue braccia di pietra (Fig. 4).

Ma quelle frane stanno lavorando operosamente e senza posa, con improvvise accelerazioni causate dai terremoti. Esse sono già riuscite a suddividere il Lago in due Laghi più piccoli, costruendo una sorta di cresta tra il bacino più settentrionale e quello posto a meridione.

Questo processo di caricamento ha forse esperimentato una qualche sorta di accelerazione alla metà del diciannovesimo secolo? Non lo sappiamo con certezza, perché sarebbe necessario effettuare un'indagine geologica al fine di accertare l'epoca alla quale far risalire i flussi detritici maggiormente significativi presenti nell'ambito dei due smottamenti. Sappiamo che nel 1879 gli aristocratici membri del Club Alpino Italiano osservarono, per l'ultima volta, un singolo Lago in assai floride condizioni; e nel 1897, alla fine del diciannvesimo secolo, Pio Rajna contemplò i due Laghi distintamente separati tramite una porzione di terreno non ricoperta dall'acqua, benché attorno fossero presenti accumuli di neve: un segnale del fatto che la cresta centrale stava diventando sufficientemente rilevata da assicurare una completa ripartizione dei due Laghi malgrado piogge e nevicate.

Un attacco mortale, come abbiamo avuto modo di illustrare in questo capitolo. Ma ancor più letale esso appare, quando lo si venga a considerare assieme alla concomitante azione legata al cambiamento climatico e al riscaldamento globale.

Finché i Laghi di Pilato, alla fine, non si estingueranno.

28 Dec 2020

Pontius Pilate and the shape of the waters /21. Climate change: is the Lake's end near?

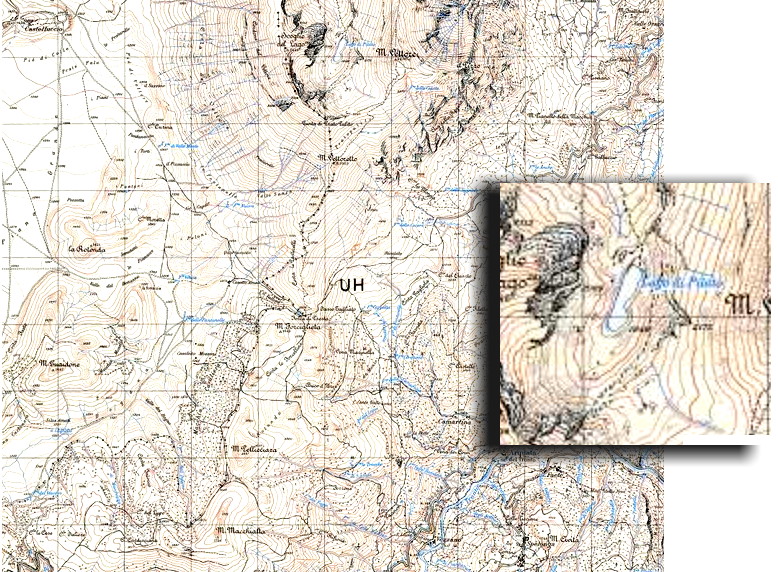

At the end of the nineteenth century, Vittorio Sella, the great alpinist and photographer, whose uncle was Quintino Sella, the founder of the Italian Alpine Club, ascended a number of elevated peaks of the Alps to portray the gorgeous, panoramic vistas with his camera equipped with large, high-quality photographic plates.

At the time, he did not know; yet he was dramatically contributing to the advancement of contemporary climatology, by providing future scientists with invaluable evidences of a most critical environmental process.

This process was climate change.

His pictures of alpine glaciers are being presently used by modern photographers and researchers to assess the fast-paced retreat of the ice masses under the pressure of global warming. Fabiano Ventura's project "On the trail of the glaciers" is currently documenting, with stunning photographs taken from the same positions as Vittorio Sella's, the shrinking of the glaciers which lie amid the Italian Alps: the decrease in snowfalls and the ever-growing heat which floods the icy surfaces during the warmest summers in the last one hundred fifty years are speeding up a melting process that was possibly triggered centuries ago by the start of the Industrial Revolution, in Europe initially and then throughout the whole world (Fig. 1).

Similar studies are being conducted in other portions of the Alps: in Switzerland, other astounding pictures provide a sad vision of the doom that is looming over all alpine glaciers, with a dramatic retreat of the ice and a depletion of the stocks of frozen water (Fig. 2).

On a general, worldwide basis the fate of glaciers is gloomily outlined in the "Fifth Assessment Report on Climate Change" (2013) edited by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change:

«More than 600 glaciers have disappeared over the past decades. Even if there is no further warming, many more glaciers will disappear. It is also likely that some mountain ranges will lose most, if not all, of their glaciers. [...] Larger glaciers will continue to shrink over the next few decades, even if temperatures stabilise. Smaller glaciers will also continue to shrink, but they will adjust their extent faster and many will ultimately disappear entirely».

This is the incoming death of glaciers. A termination which certainly is strongly linked with the condition of our Lakes set in the Apennines, between the provinces of Umbria and Marche.

Because climate change, of course, is not limited to Alps.

A remarkable paper issued by the Regional Administration for Environment and Preservation of Emilia-Romagna in 2010 ("Climatology and annual variations of snow on the Apennine in Emilia-Romagna", De Bellis et al.) analyses the trends in snowfalls and accumulated snow in a mountainous region which lies not far from the Sibillini Mountain Range, on their northwestern side. According to the study, the climatology of snow in the southern portion of the investigated area, the Romagna, is similar to that «of the Adriatic versant of Central Apennines», which means the Sibillini region.

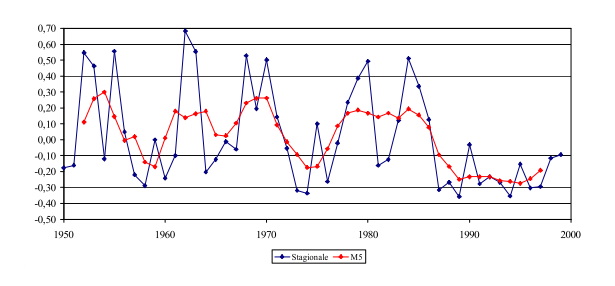

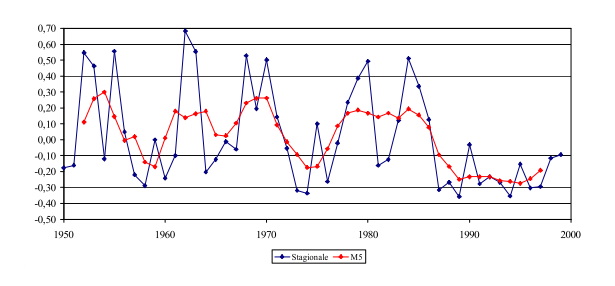

The diagrams processed by the researchers on the amount of snowfalls in the area in the second half of the twentieth century are highly significant. The thickness of the accumulated snow in winters, as measured by a number of stations set across the Emilia-Romagna Apennines, shows a dramatic decrease in the deposited quantities of snow at the end of the 1980s (Fig. 3). This is linked to a steady growth of the maximum temperatures in winters on those same mountainous reliefs across the years.

In the research paper, an interesting correlation is established with a global index specifically used in contemporary climatology: the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO).

The NAO is a large-scale atmospheric phenomenon which affects climate variations across the European and northern-Atlantic regions. It is connected to the positions and seasonal parameters of the Azores High and Icelandic Low, with a strong influence on jet streams at tropospheric altitude. According to the study, the strong decrease in snowfalls observed in the Romagna region in the 1980s «is matched by the very same period in which the NAO index begins to grow».

So the NAO index appears to be a main factor in the triggering of snowfalls and snow accumulation over the land of Emilia-Romagna and the nearby Apennines; and its influence extends across the whole European territory, as shown by a Swiss study and a further Romanian research carried out respectively on the Alps and the Carpathian Mountains, which both led to a same conclusion.

Vanishing glaciers, decrease in rainfalls and snowfalls, ominous variations of the North Atlantic Oscillation: all these factors, all linked to the current change which is affecting global weather and climate, are marking the potential, impending end of the Lakes of Pilate.

And we want to conclude this sorrowful paragraph by providing a true, unmistakable vision of the main factor which will lead the Lakes of Mount Vettore to their final death.

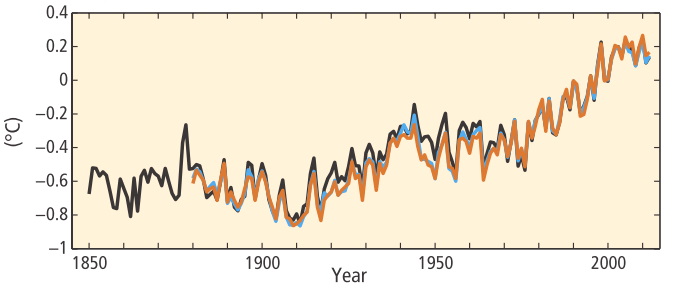

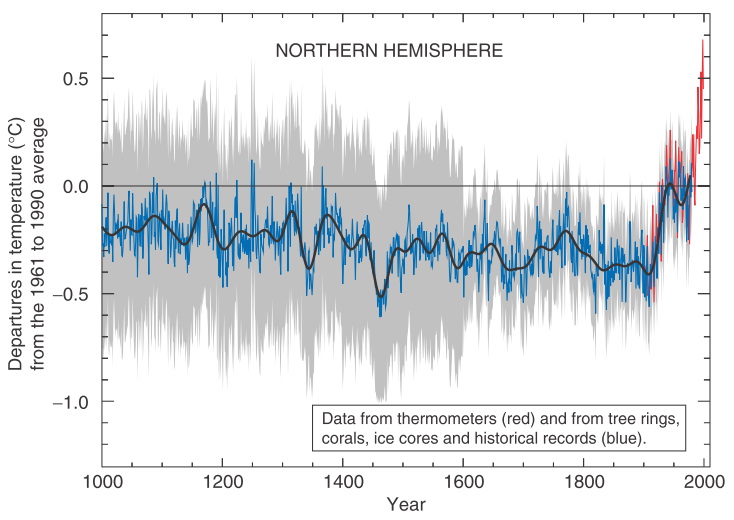

In the previous paragraph, dedicated to the 'Little Ice Age', we already saw a diagram taken from the IPCC's "Third Assessment Report on Climate Change" (2001), showing, on its rightmost portion, the rapid, amazing, almost unbelievable rise in global temperature observed from the middle of the nineteenth century and up to our current days.

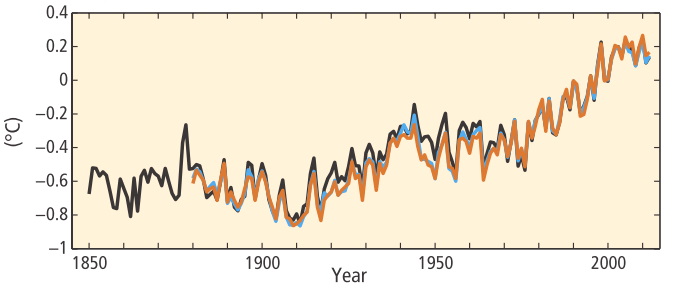

A further, astounding, updated view is provided by a diagram presented in the "Climate Change 2014 Report" issued by the IPCC.

It's a diagram which shows the global average temperatures between 1850 and 2012 (Fig. 4).

It rises. And rises. And rises. Very fast.

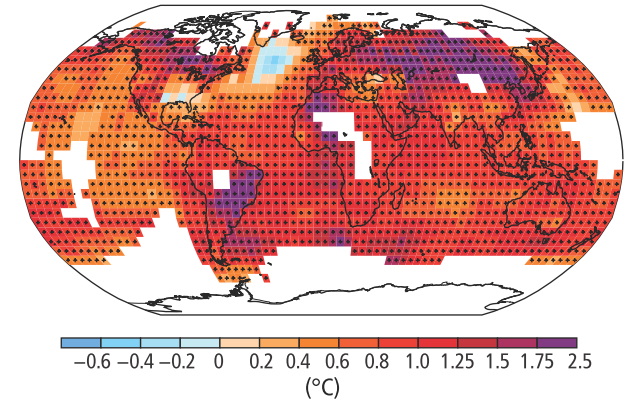

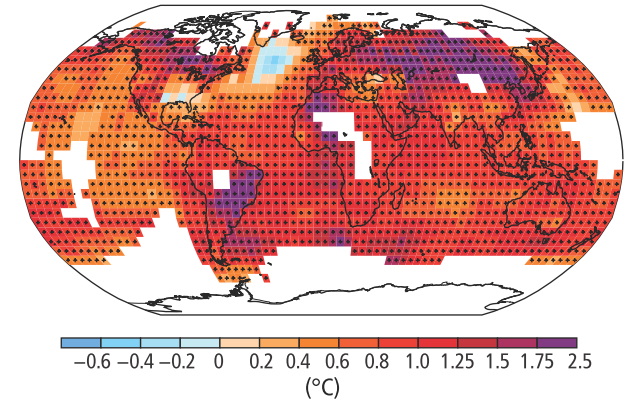

And another diagram is shown in the same report (Fig. 5).

It's our world. The Earth. And it is warming up. Quickly.

Increased heat. Vanishing glaciers. Less snow. Less rain. In this gloomy framework, there is no question about the final destiny of the Lakes of Pilate, in the Sibillini Mountain Range.

They will disappear. Their cradle of rock will remain eventually empty.

And this will not be a problem only for a small, legendary, fascinating basin of water lost amid the Mountains of the Sibyl.

This will be a problem for mankind as a whole.

Ponzio Pilato e la forma delle acque /21. Cambiamento climatico: la fine dei Laghi è vicina?

Alla fine del diciannovesimo secolo, Vittorio Sella, il grande alpinista e fotografo, nipote di Quintino Sella, il fondatore del Club Alpino Italiano, scalò una serie di elevati picchi appartenenti alla catena delle Alpi al fine di ritrarne i meravigliosi panorami con la sua macchina fotografica, equipaggiata con lastre di grandi dimensioni e di alta qualità.

A quell'epoca, egli non poteva ancora saperlo; eppure, egli stata contribuendo in modo straordinario al progresso della climatologia contemporanea, fornendo ai futuri scienziati prove di importanza fondamentale in relazione a un processo ambientale estremamente critico.

Quel processo era il cambiamento climatico.

Le sue immagini dei ghiacciai alpini sono oggi utilizzate dai moderni fotografi e ricercatori per valutare il rapido ritrarsi delle masse di ghiaccio sotto la pressione del riscaldamento globale. Il progetto di Fabiano Ventura "Sulle tracce dei ghiacciai" sta oggi documentando, con impressionanti fotografie scattate dalle medesime posizioni un tempo utilizzate da Vittorio Sella, la riduzione dei ghiacciai che si trovano tra le vette delle Alpi italiane: la diminuzione delle precipitazioni nevose e il calore ininterrottamente crescente che si diffonde sulle superfici ghiacciate durante le più roventi estati degli ultimi centocinquanta anni stanno provocando l'accelerazione di un processo di scioglimento che fu forse attivato, alcuni secoli fa, dall'inizio della Rivoluzione Industriale in Europa e, in seguito, in tutto il mondo (Fig. 1).

Ricerche analoghe sono oggi in corso in altre sezioni delle Alpi: in Svizzera, ulteriore immagini, del pari strabilianti, rendono disponibile un'amara visione del destino che incombe su tutti i ghiacciai alpini, con una drammatica riduzione dei ghiacci e il depauperamento delle riserve di acqua congelata (Fig. 2).

Da un punto di vista più generale e globale, il fato dei ghiacciai è tristemente delineato nel "Quinto Rapporto di Valutazione sul Cambiamento Climatico" (2013), pubblicato dal Gruppo Intergovernativo sul Cambiamento Climatico (IPCC):

«Più di 600 ghiacciai sono scomparsi nel corso degli ultimi decenni. Se anche non vi fosse un ulteriore riscaldamento, molti altri ghiacciai sono comunque destinati a svanire. È anche probabile che molte catene montuose vedranno la perdita della maggior parte dei propri ghiacciai, se non addirittura di tutti. [...] I ghiacciai di maggiori dimensioni continueranno a ridursi nel corso dei prossimi decenni, anche se la temperatura si stabilizzasse. I ghiacciai più piccoli continueranno parimenti a ridursi, ma la loro estensione subirà mutamenti più rapidi e molti di essi alla fine scompariranno del tutto».

È questa la fine imminente dei ghiacciai. Una conclusione che, certamente, è fortemente connessa alla condizioni dei nostri Laghi situati tra gli Appennini, ai confini delle regioni dell'Umbria e delle Marche.

Perché il cambiamento climatico, naturalmente, non è limitato alle Alpi.

Un interessantissimo studio elaborato dall'Agenzia Regionale Prevenzione e Ambiente dell'Emilia-Romagna nel 2010 ("Climatologia e variabilità interannuale della neve sull’Appennino Emiliano-Romagnolo", De Bellis et al.) analizza le tendenze nelle precipitazioni nevose e negli accumuli di neve in una regione montuosa che giace non lontano dai Monti Sibillini, in direzione nordoccidentale. Secondo questo studio, la climatologia della neve nella porzione territoriale più meridionale, corrispondente alla Romagna, è analoga a quella «del versante Adriatico dell’Appennino Centrale», che corrisponde proprio ai Monti Sibillini.

I diagrammi elaborati dai ricercatori in relazione alle quantità di precipitazioni nevose nell'area nel corso della seconda metà del ventesimo secolo sono estremamente significativi. Lo spessore del manto nevoso invernale, misurato tramite una serie di stazioni distribuite lungo l'Appennino emiliano e romagnolo, mostrano una drastica diminuzione nelle quantità di neve depositatesi al suolo alla fine degli anni 1980 (Fig. 3). Ciò appare essere legato a un costante incremento delle temperature massime rilevate nelle stagioni invernali su questi stessi rilievi montuosi attraverso gli anni.

Nell'articolo di ricerca viene inoltre stabilita un'interessante correlazione con un indice globale specificamente utilizzato dalla climatologia contemporanea: l'Oscillazione Nord Atlantica (North Atlantic Oscillation - NAO).

Il NAO è un fenomeno atmosferico su larga scala che agisce sulle variazioni climatiche nell'area dell'Europa e nella regione del Nord Atlantico. Esso è connesso con la posizione e i parametri stagionali dell'Anticiclone delle Azzorre e della Depressione d'Islanda, con una significativa influenza sui flussi delle correnti a getto ad altitudine troposferica. Secondo lo studio, la drastica diminuzione di precipitazioni nevose osservata nella regione della Romagna negli anni 1980 «coincide esattamente con il momento in cui l’indice NAO inizia la sua crescita».

Dunque l'indice NAO appare essere un fattore primario per l'innesco di precipitazioni nevose e l'accumulo di nevi nell'area dell'Emilia-Romagna e degli adiacenti Appennini: e la sua influenza si estende su tutto il territorio europeo, come mostrato da uno studio svizzero e da un'ulteriore ricerca romena, analisi relative rispettivamente alle Alpi e ai Carpazi: due studi che hanno condotto, entrambi, alle medesime conclusioni.

Ghiacciai che svaniscono, diminuzione delle piogge e delle nevi, negative variazioni dell'Oscillazione Nord Atlantica: tutti questi fattori, interconnessi tra loro e con il cambiamento che sta oggi modificando il tempo meteorologico e il clima globale, stanno segnando la potenziale, incombente fine dei Laghi di Pilato.

E vogliamo concludere questo amaro paragrafo rendendo disponibile una veridica, inequivocabile visione del principale fattore che condurrà i Laghi di Pilato verso la propria morte finale.

Nel precedente paragrafo, dedicato alla 'Piccola Era Glaciale', abbiamo già avuto occasione di mostrare un diagramma tratto dal "Terzo Rapporto di Valutazione sul Cambiamento Climatico" elaborato dall'IPCC, il quale presenta, nella porzione situata più a destra, il rapido, strabiliante, quasi incredibile incremento della temperatura globale osservato a partire dalla metà del diciannovesimo secolo e fino ai nostri giorni.

Un'ulteriore visione, aggiornata e che lascia senza parole, ci viene fornita da un diagramma presentato nel "Rapporto sul Cambiamento Climatico 2014" pubblicato dallo stesso IPCC.

Si tratta di un diagramma che mostra l'andamento delle temperature medie globali tra il 1850 e il 2012 (Fig. 4).

La temperatura cresce. E cresce. E cresce. Molto rapidamente.

E un altro diagramma viene mostrato in quello stesso rapporto (Fig. 5).

È il nostro mondo. La Terra. E si sta riscaldando. Velocemente.

Calore crescente. Ghiacciai in scioglimento. Meno neve. Meno pioggia. In questo oscuro scenario, non vi è alcun dubbio di quale possa essere il destino finale dei Laghi di Pilato, posti tra i Monti Sibillini.

Essi scompariranno. La loro culla di pietra rimarrà infine vuota.

E non sarà solo un problema per un piccolo, leggendario, affascinante specchio d'acqua perduto tra le vette dei Monti della Sibilla.

Sarà un problema per l'intera umanità.

27 Dec 2020

Pontius Pilate and the shape of the waters /20. Climate change: a golden, glacial period

It was in the fourteenth century that winters began to get cooler and snow invaded Europe: the continent was entering what scientists call the Little Ice Age (LIA). An age of lower temperatures which will last half a millennium.

There is no widespread agreement among researchers as to the characteristics, reasons and accurate dating of this weather phenomenon, which seems to have affected the Northern Hemisphere only. Its definition is the result of a number of studies involving many heterogenous disciplines and sources, including history, literature, climatology, glaciology and even figurative arts. However, it is a fact that a series of clues appear to indicate that at some point in time Europe became colder, and that this moderate cooling lasted, with variations, until the mid of the nineteenth century.

The appearance of colder weather conditions over Europe was not distributed geographically in a homogeneous way. First reports of a specific cooling trend refer to Iceland and pack ice drifting around the northern-Atlantic isle ("Abrupt onset of the Little Ice Age triggered by volcanism and sustained by sea-ice/ocean feedbacks", Miller et al., 2012):

«The expansion of ice caps after Medieval times was initiated by an abrupt and persistent snowline depression late in the 13th Century, and amplified in the mid 15th Century. [...] Sea ice was rarely present on the North Iceland shelf from 800 AD until the late 13th Century, when an abrupt rise in sea-ice proxies suggests a rapid increase in Arctic Ocean sea ice export, followed by another increase around 1450 AD, after which sea ice was continuously present until the 20th Century. [...] LIA summer cold and ice growth began abruptly between 1275 and 1300 AD, followed by a substantial intensification 1430–1455 AD».

Further evidences of a European-wide cooling are provided by the occurrence of the Great Famine in the years 1315-1317, when unusual cold and heavy, persistent rains struck a large portion of Europe and caused an extensive failure of crops. The river Thames froze many times in the subsequent centuries, as attested by paintings as well (Fig. 1). The winter season between 1709 and 1710 was known in Europe as "The Great Frost": it is considered as one of the coldest winters ever occurred in the Continent. And, throughout the LOI age, glaciers in the Alps seem to have gained in extension, as illustrated in a further research paper ("Glacier fluctuations during the past 2000 years", Solomina et al., 2016):

«In the Alps the maximum extent of the glaciers was reached in the 17th - 19th centuries [...]. A maximum glacier advance also occurred in the Alps in the 14th century».

Another study ("The Little Ice Age signature in a 700-year high-resolution chironomid record of summer temperatures in the Central Eastern Alps", Ilyashul et al., 2018) provides evidences of «a notable decreasing trend of - 1.2 °C from ca AD 1300 until ca AD 1800 [... with] a prolonged period of predominantly cooler conditions during AD 1530–1920, which is temporally largely equivalent to the climatically defined LIA in Europe. [...] The main LIA phase appears to have consisted of two cold time intervals divided by slightly warmer episodes in the second half of the 1600s. The most severe cooling occurred during the eighteenth century».

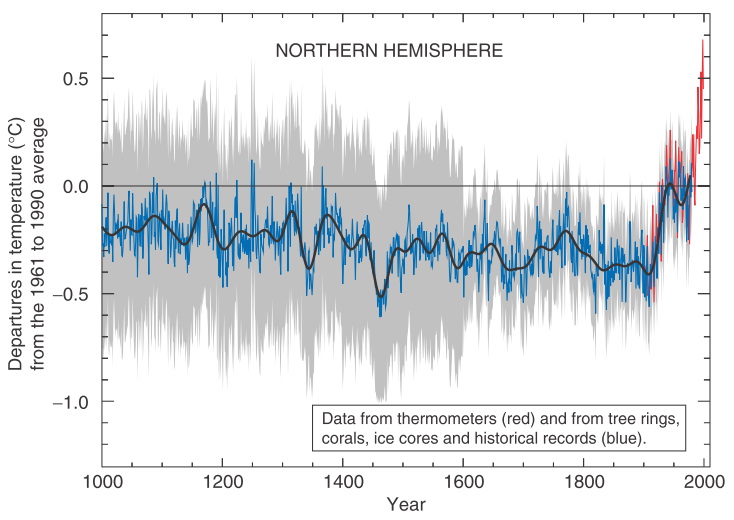

Bits and pieces of information, which scientists are trying to match with the available data on average estimated temperatures, with an eye to the subsequent period of dramatic warming due to the Industrial Revolution and contemporary human activity, as shown in the diagram included in the Third Assessment Report on Climate Change (2001) elaborated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: a decreasing line from the Middle Ages to 1850, the footprint of the Little Ice Age, and then a fast rise towards today's global warming temperature levels (Fig. 2).

So, in past centuries the weather in Europe was cooler. Hubert Lamb, a passionate, early forerunner of the investigation into past climate variations, in his book "Climate, History and the Modern World" (1982) wrote that «snowfall was much heavier than recorded before or since, and the snow lay on the ground for many months longer than it does today». It can be assumed that snowfalls were more abundant and accumulated snow persisted on mountaintops for longer times.

What happened in Italy? What happened to our Lake of Pilate during the Little Ice Age?

A number of sources and reports are related to specific events occurred in the Italian peninsula across many centuries. As an example, an insight paper ("The Little Ice Age in Italy from documentary proxies and early instrumental records", Camuffo et al., 2014) highlights the years in which the Lagoon of Venice froze totally or partially: extremely cold winters occurred in 1408, 1413, 1477, 1511, 1560, 1684, 1776, 1820 and 1864, with a number of less severe episodes interspersed amid the listed dates, with only a handful of occurrences being registered during the twentieth century (Fig. 3).

So, while glaciers in the Alps extended, the prolonged effects of cooling also acted on the southern portion of Europe, including Italy, as inferred by another scholar ("The 'Little Ice Age' and its Geomorphological Consequences in Mediterranean Europe", Grove, 2001):

«Alpine glacier advances in the 'Little Ice Age' took place in the decades around 1320, 1600, 1700 and 1810. They were the outcome of snowier winters and cooler summers than those of the twentieth century. Documentary records from Crete in particular, and also from Italy, southern France and southeast Spain point to a greater frequency in Mediterranean Europe's mountainous regions of severe floods, droughts and frosts at times of 'Little Ice Age' Alpine glacier advances. Deluges, when more than 200 mm of rain fall within 24 hours, are most frequent on mountainous areas near the coast».

Therefore, the climate in Italy between the fourteenth century and the mid of the nineteenth century was certainly cooler, and more snow and rain used to fall on the whole peninsula. Including mountainous reliefs.

Has all this any relevance to the issue which concerns the shape of the Lake of Pilate, in the Sibillini Mountain Range, at the center of Italy?

Yes indeed. This is actually the sort of climate-related finding we expected to register. Because the epoch of the Little Ice Age is actually the very same multicentennial period during which the Lake of Pilate has being presenting itself as a single, gloomy, ominous basin.

A Lake effectively fed by rainfalls and snowfalls. And made healthy by generous accumulations of snow deposited over the steep versants of Mount Vettore's glacial cirque.

A single Lake, as it was described by the literary sources dating back to the fourteenth century (Petrus Berchorius) and the fifteenth (Antoine de la Sale), and then across the subsequent centuries in written references and geographical maps. Always a single basin of dark waters, apart from the specific mentions provided by manuscript Vat. Lat. 5241 and Father Fortunato Ciucci, which both portray a dual-shaped Lake observed during the summer season.

The Little Ice Age, a European-wide climate-related phenomenon marked by lower temperatures and a general though moderate cooling of the whole continent, is possibly the main reason for the semblance of the Lake of Pilate across many centuries, and up to the second half of the nineteenth century.

At that time, something began to change.

As we comprehensively illustrated in the previous paragraphs of the present research paper, the Lake of Pilate was gradually turning into two separate Lakes: the Lakes of Pilate as we know them today.

And one of the main drivers for the transformation of our necromantic basin is always the same: climate change.

Or, more appropriately, man-driven climate change.

Ponzio Pilato e la forma delle acque /20. Cambiamento climatico: un dorato periodo glaciale

Fu nel quattordicesimo secolo che gli inverni iniziarono a diventare più freddi e la neve invase l'Europa: il continente stava entrando in ciò che gli scienziati chiamano la Piccola Era Glaciale ('PEG', o 'Little Ice Age', 'LIA', in inglese). Un'era di temperature più basse che durerà per mezzo millennio.

Tra i ricercatori, non esiste un consenso unanime in merito alle caratteristiche, alla cause e ad una precisa datazione di questo fenomeno climatico, che parrebbe avere agito solamente sull'emisfero nord del mondo. La sua definizione è il risultato di una serie di studi che coinvolgono molte differenti discipline e fonti eterogenee, tra le quali la storia, la letteratura, la climatologia, la glaciologia e anche le arti figurative. Eppure, è un fatto che una serie di elementi appaiano indicare come a un certo punto nel tempo l'Europa sia divenuta più fredda, e che questo moderato raffreddamento sia durato, con alcune variazioni, fino alla metà del secolo diciannovesimo.

L'instaurazione di condizioni meteorologiche più fredde sull'Europa non è stata caratterizzata da modalità geograficamente omogenee. I primi resoconti concernenti una specifica tendenza al raffreddamento sono riferiti all'Islanda e al ghiaccio marino alla deriva attorno all'isola del Nord Atlantico ("Abrupt onset of the Little Ice Age triggered by volcanism and sustained by sea-ice/ocean feedbacks", Miller et al., 2012):

«L'espansione delle coperture ghiacciate dopo il periodo medievale ebbe inizio con un'improvvisa e persistente depressione portatrice di neve nel tardo tredicesimo secolo, che si amplificò alla metà del quindicesimo. [...] Il ghiaccio marino era stato raramente presente sulla piattaforma dell'Islanda settentrionale tra l'800 d.C. e il tardo tredicesimo secolo, finché un drastico incremento dei marcatori relativi al ghiaccio marino non hanno iniziato a suggerire il verificarsi di una rapida crescita nella produzione di ghiaccio proveniente dall'Oceano Artico, seguita da un ulteriore incremento attorno al 1450 d.C.; dopo tale data, il ghiaccio marino risulta essere continuativamente presente fino al ventesimo secolo. [...] Le fredde estati della Piccola Era Glaciale e la crescita dei ghiacci ebbero bruscamente inizio tra il 1275 e il 1300, e furono seguiti da una sostanziale intensificazione tra il 1430 e il 1455».

Ulteriori evidenze relative a un raffreddamento dell'intera Europa sono fornite dal verificarsi della Grande Carestia degli anni 1315-1317, quando piogge fredde, intense e persistenti, aventi carattere straordinario, colpirono una vasta porzione dell'Europa e causarono una estesa perdita dei raccolti. Nel corso dei secoli successivi, le acque del fiume Tamigi si congelarono molte volte, così come testimoniato anche da vari dipinti (Fig. 1). La stagione invernale che si collocò tra il 1709 e il 1710 fu conosciuta in Europa come "Il Grande Inverno": essa è considerata come uno degli inverni più freddi mai occorsi nel continente. E, attraverso tutta la Piccola Era Glaciale, i ghiacciai delle Alpi avrebbero incrementato la propria estensione, come illustrato in un'ulteriore ricerca ("Glacier fluctuations during the past 2000 years", Solomina et al., 2016):

«Nelle Alpi la massima estensione dei ghiacciai fu raggiunta tra i secoli diciassettesimo e diciannovesimo [...]. Un picco nell'avanzamento dei ghiacciai si verificò nelle Alpi durante il quattordicesimo secolo».

Un altro studio ("The Little Ice Age signature in a 700-year high-resolution chironomid record of summer temperatures in the Central Eastern Alps", Ilyashul et al., 2018) presenta alcune evidenze relative a «una significativa tendenza alla riduzione delle temperature di - 1.2 °C dal 1300 al 1800 [... con] un prolungato periodo in cui hanno prevalso condizioni più fredde tra il 1350 e il 1920; tale periodo è largamente equivalente, dal punto di vista degli intervalli temporali, con la definizione climatica di Piccola Era Glaciale in Europa. [...] Sembrerebbe che la fase principale della PEG sia consistita in due differenti intervalli di tempo più freddo, separati da episodi moderatamente più caldi occorsi nella seconda metà del 1600. Il raffreddamento più intenso sarebbe occorso durante il diciottesimo secolo».