21 Feb 2020

Sibillini Mountain Range, a cave and lake to the Otherworld /5. Beyond the legendary layers, a chthonian passageway in the central Apennines

At the end of our thrilling journey into the otherwordly character of the legends of the Sibyl's Cave and the Lake of Pilate, in the Italian Sibillini Mountain Range, let's summarise our extraordinary findings and far-reaching, daring assumptions about a legendary otherwordly passageway which might have been possibly situated, by an antique tradition that has left some faint traces in the known literature, among the peaks of the central Apennines.

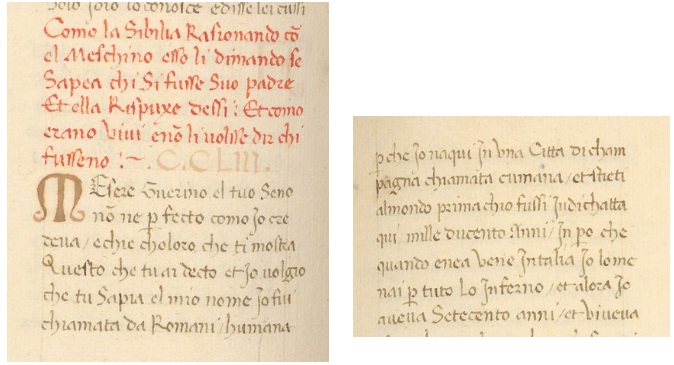

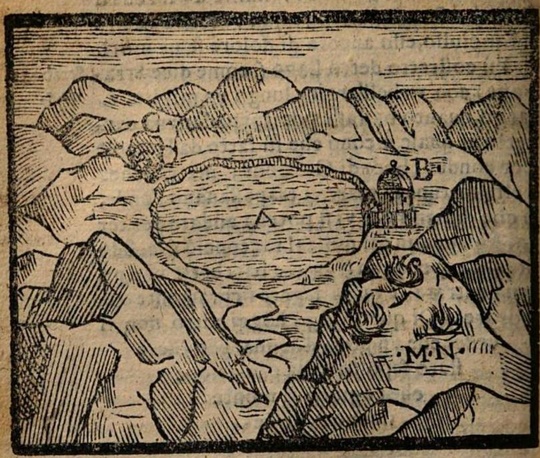

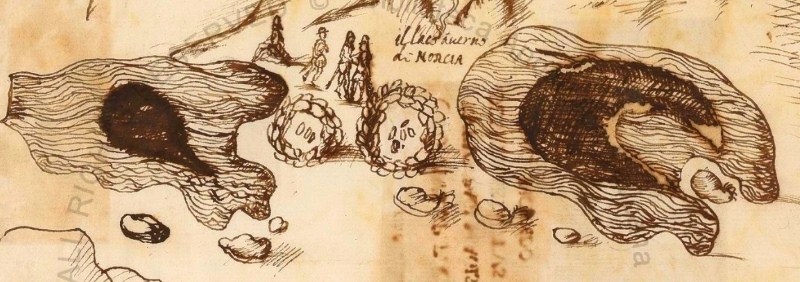

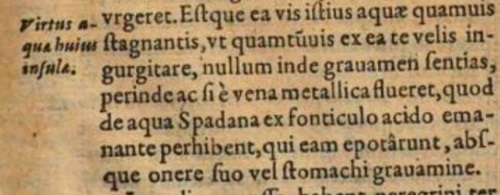

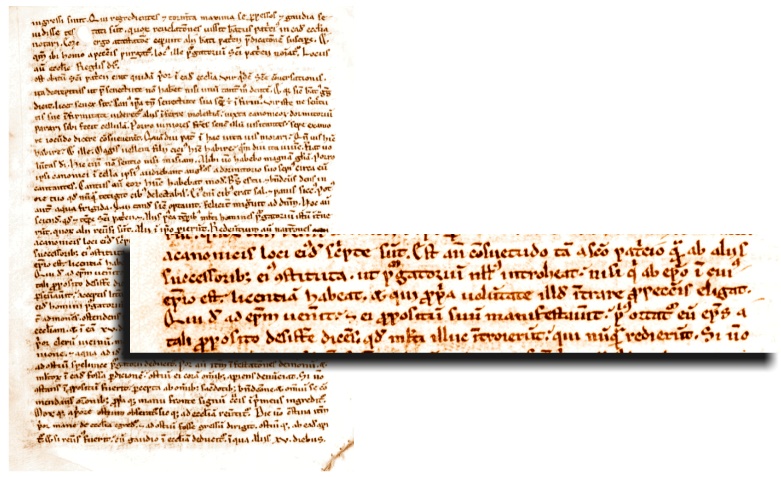

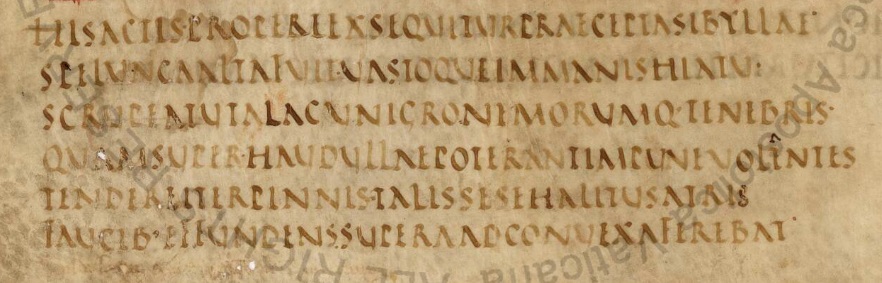

For centuries, amid the cliffs and ravines of the Sibillini Mountain Range, in central Italy, two renowned legends have been telling their tales to the hearts of men coming from all over Europe: the Sibyl's Cave, placed on a crowned mountaintop; and, only a few miles away, the Lake of Pilate, encircled by daunting, precipitous walls of sheer rock. An unchaste Sibyl was believed to dwell in the Cave under the mount, in a subterranean realm full of handsome damsels of a demonic nature (Fig. 1). A Roman prefect, that same officer who sent Jesus Christ to the Cross, was reputed to have been cast into the Lake's icy waters, his body as cursed as a part of the Devil's body. Two fifteenth-century authors, Andrea da Barberino and Antoine de la Sale, wrote literary works about the two legends. And the fame of the two sites ran across the nations for hundreds of years (Fig. 2).

However, something seems not to add up.

As we already discussed in many previously-published research papers, there is something wrong with all the commonly-accepted legendary framework: a Sibyl, possibly the Cumaean; Pontius Pilate and his tragic doom; centuries and centuries of visits to the two remote, impracticable sites.

A detailed study of the two legendary narratives clearly shows that the Apennine Sibyl is not a classical oracle, but a descendant of Morgan le Fay and her necromantic companion Sebile, two characters which belong to the Matter of Britain and the Arthurian cycle, staged in a number of chivalric romances and poems written centuries earlier in a northern-European setting. A further analysis of the early-Christian and medieval tale concerning Pontius Pilate shows that his many legendary resting places, located in different areas across Europe, have nothing to do with the Italian Apennines.

So, in our view and as a result of the investigations we have already released, we can confidently assume that no Sibyl has ever lived amid the peaks of the Sibillini Mountain Range. And no Pontius Pilate has ever been cast into any lake in central Italy. The two narratives do not belong to this portion of the land of Italy. The two famous legends are not original. They both settled here coming from distant territories.

But why did they come and settle right here?

If we remove the two literary layers, which are to be considered as additional legendary overlays, and we start to look attentively into the underlying characters of the legends which mark the two sites, the Cave and the Lake in the Sibillini Mountain Range, we run into a number of common features: necromancy was performed at either sites; legendary demons were believed to dwell in both; tempests and devastations were aroused by necromancers when carrying out their rituals.

Something was already there. Something that had nothing to do with Sibyls and antique Roman prefects. Something that seems to preexist the two additional, extraneous legendary layers.

We believe that the correct path we need to tread if we want to unveil the true core of the legends of the Sibillini Mountain Range leads to a specific, and somewhat unexpected, keyword: Otherworld.

Otherworld: a most ancient dream that men have been dreaming since the earliest antiquity when confronting with life and death, mortality and the divine, and, after the rise of the Christian era, the ultimate truths of salvation and punishment.

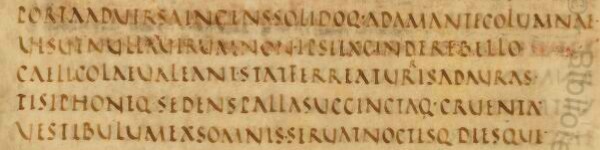

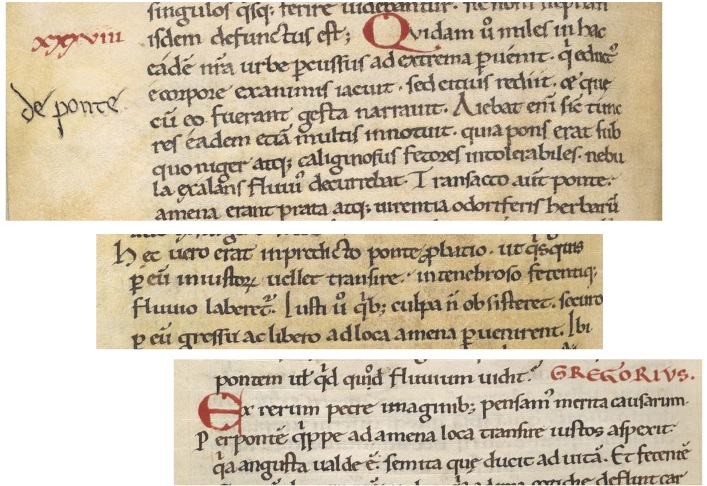

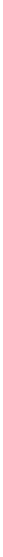

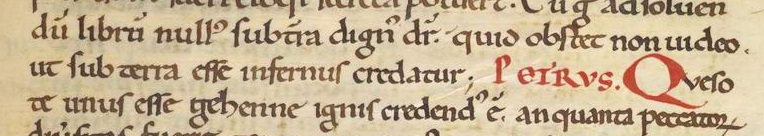

At a closer scrutiny, thoroughly performed within the present research paper, the legendary tales of the Sibyl's Cave and the Lake of Pilate appear to be marked by a number of otherwordly narrative elements. In the account written by Antoine de la Sale, a test bridge of supernatural narrowness crosses a frighftul abyss, but it gets wider as you tread on it, a typical contrivance dating back to Pope Gregory the Great's “Dialogues” and then present in a number of medieval visionary writings. Metal doors are also present, magically slamming day and night with a ceaseless crushing motion, a sort of device which is found in earlier chivalric works and is connected to otherwordly descriptions contained in the “Aeneid” and in the Greek myth of the Symplegades. Crystal rooms await the visitors, the clear sign of an afterlife setting. And the Lake is openly indicated as an entrance to Hell in an excerpt drawn from Petrus Berchorius, written in the fourteenth century. The Lake itself is called 'Lake Avernus' in a manuscripted diagram dating to the sixteenth century, thus marking a remarkable narrative correspondance with the famous, classical entryway to the House of Hades set in Cumae.

An entryway to the Otherworld: since time immemorial this has been an impious craving housed in the soul of men. A dream, a desire for a vision of the afterlife, a longing for prohibited communications with the dead, a quest for obtaining forbidden wishes. And the search for an ultimate truth.

In the present paper, we have explored the many literary instances, part of a well-established Western tradition, which narrate the legendary tales of passageways into the Otherworld, in the form of a 'nekyia', the summoning of the shadows of the dead at the entrance of the gloomy realm, or as a 'katabasis', a journey which brings a mortal man through that passageway and into a land of dread. Such are the ghastly journeys performed by visionary heros in the otherwordly literature of the Western culture. In classical antiquity, Ulysses and his visit to Hades, then Aeneas and his journey into the Avernus, with the Cumaean Sibyl as a guide. And subsequently, the visions of early Christianity: St. Paul and his visionary dreams of Hell, Pope St. Gregory I the Great with his soldier, the first in a series of knights travelling to the Otherworld. And, then again, Ireland, with its medieval descriptions of appalling journeys into the excruciating torments and punishments inflicted to the sinners: the “Vision of St. Adamnán”, the “Vision of Tnugdalus”, and the “Purgatory of St. Patrick”.

But only two are the journeys that are utterly special, the travels into the Otherworld par excellence: these are travels that are performed not in a mere vision, but in actual reality. With a man's physical body.

In the Western literary tradition, two are the most renowned places on Earth where to initiate such a horrifying travel. Two 'hot spots'. Two crevices pierced in the continuity of our ordinary world. Two fissures, dreadfully opened to legendary physical visions of a subterranean, chthonian Hell.

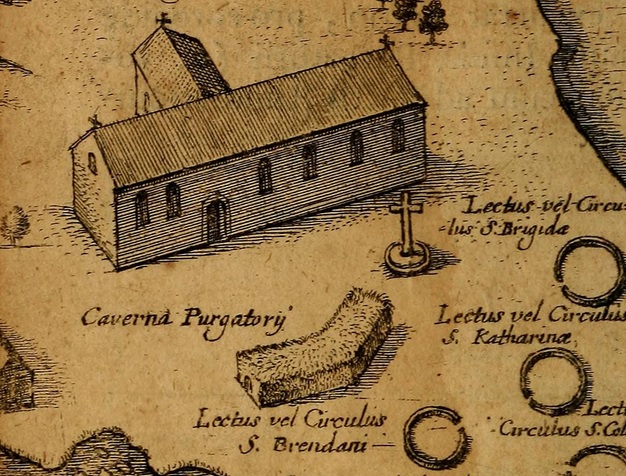

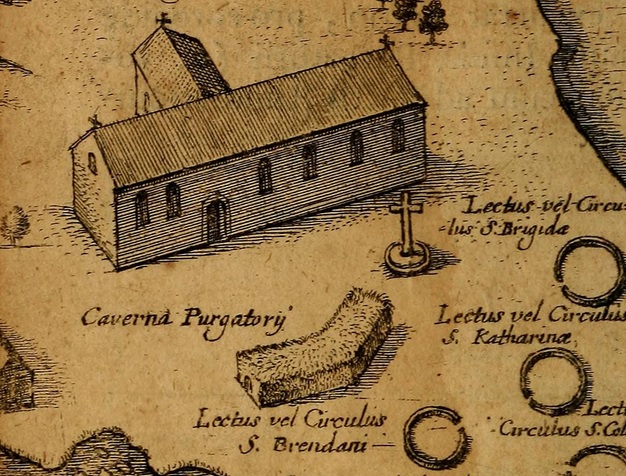

The first is at Cumae, by the Lake Avernus, in southern Italy. And the second is at the Purgatory of St. Patrick, Lough Derg, Co. Donegal, in northern Ireland.

At those two sites, living men could be so fool as to make an attempt at crossing the gates which must never be crossed. Two passageways to the Otherworld. Two entryways to an afterlife inhabited by legendary demonic powers.

The two traditional entrances were widely known throughout the Middle Ages and across the entire Europe. They had been the subjects of many literary works, from the “Aeneid” to the “Tractatus de Purgatorio Sancti Patricii” and the “Legenda Aurea”. People engaged themselves in difficult journeys as far as the two listed locations with the aim to see, and cross, the contact points between two worlds, which are normally separated: the world of the living, and the realm of the dead.

By an odd chance, not due to any specific, traceable reason, both sites were indicated by the same pair of landmarks: a lake and a cave for both, two landforms which fully identified the two sites on the surface of Earth, and were known as such.

Why Cumae and Lough Derg? Why did passageways to the Otherworld happen to settle exactly in those two locations? Caves were in the volcanic soil of Cumae, that were filled to the vaulted ceilings with mephitic gases, which induced dreams, and sometimes a horrible death. A cave was also to be found at Lough Derg: on entering, sleep overwhelmed the already exhausted pilgrims, who then dreamt and had nightmares, possibly out of the lack of breathable air, and, maybe, owing to the presence of poisonous gases arising from the marshy ground.

Lake Avernus and its cave at Cumae. Lough Derg and its cave in Ireland. But a third set of landmarks, similarly made up by a Lake and a Cave, was also present in central Italy.

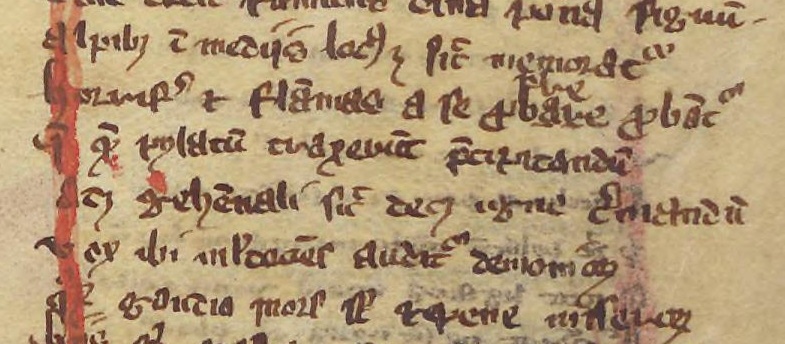

It was the Sibyl's Cave and the Lake of Pilate in the Sibillini Mountain Range. Set only a few miles away from each other (Fig. 3).

The same geographical configuration, as at Cumae and Lough Derg. A demonic presence registered and necromantic rituals being performed at this third Italian site, too. Otherwordly traits, which marked the two landforms amid the Apennines as well.

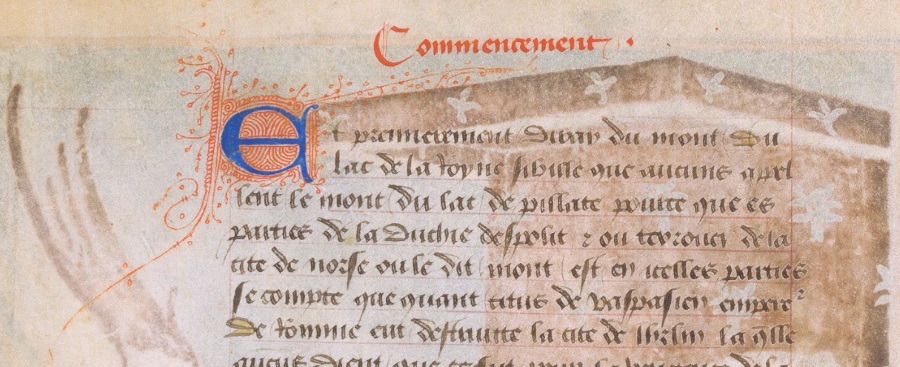

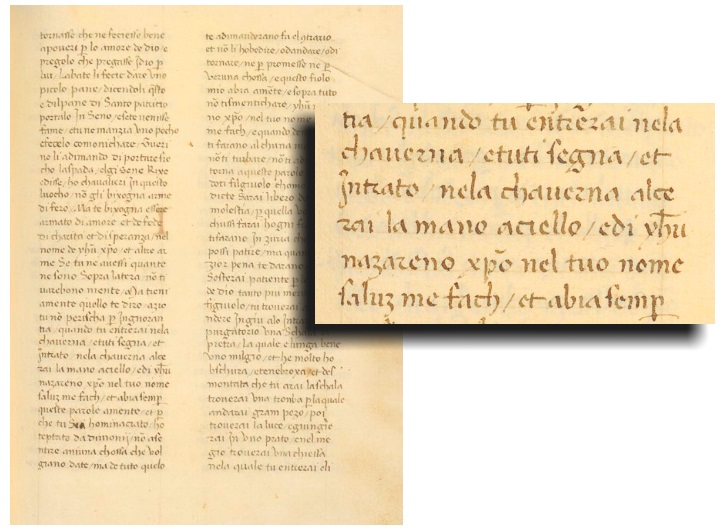

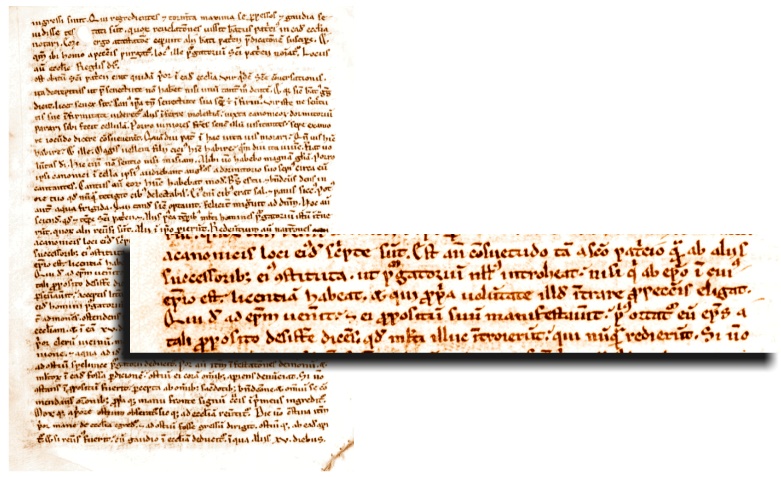

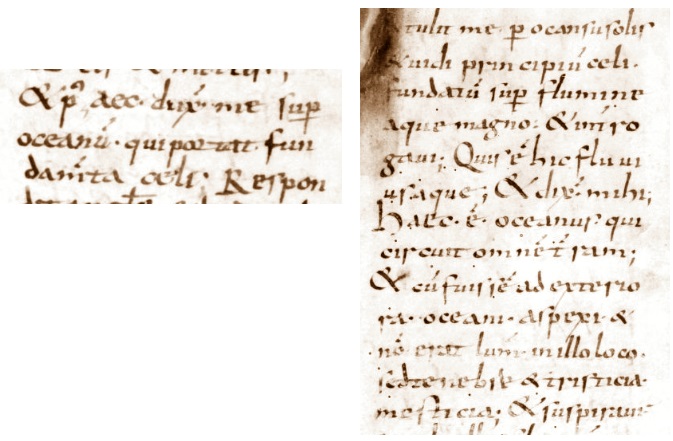

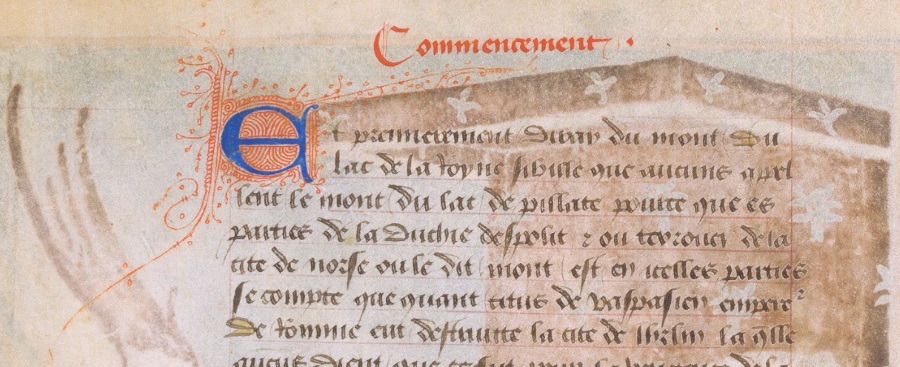

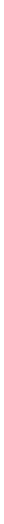

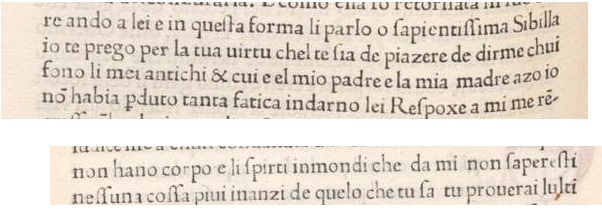

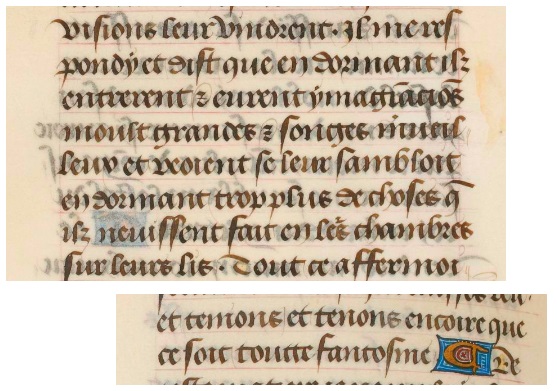

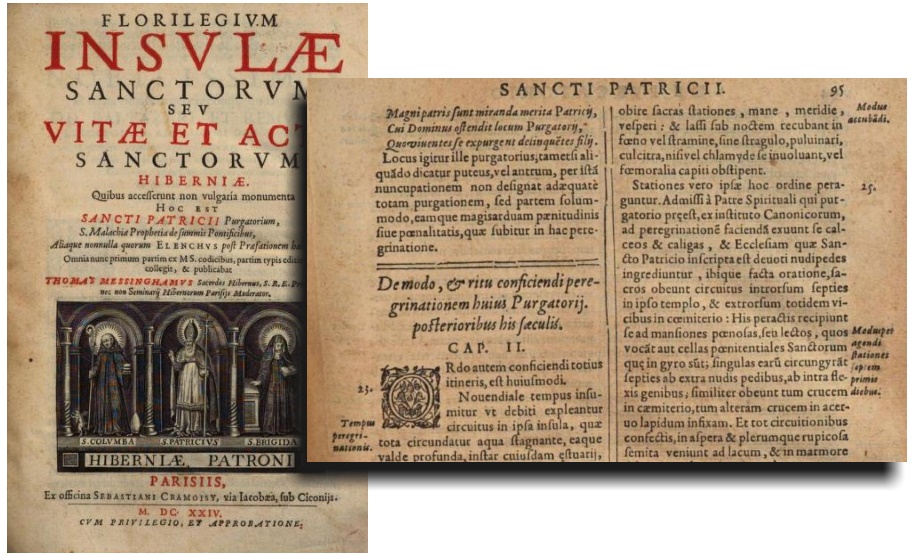

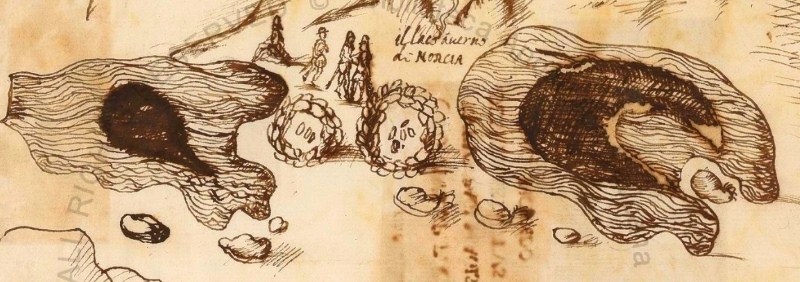

And we may also try to assume, in centuries which precede the fifteenth, when narratives were only oral and photographic imaging was still centuries ahead, that the Sibyl's Cave and the Lake of Pilate were essentially close enough to be considered as a single legendary system, without the differentiation of which we still find a trace today in their two distinct names, Sibyl's and Pilate's. It is Antoine de la Sale himself who seems to point to this research direction, when he says the following words at the very opening of his “The Paradise of Queen Sibyl” (Fig. 4):

«And first I will tell you of the mountain of the lake of Queen Sibyl, which some name the mountain of the lake of Pilate [...] part of the Duchy of Spoletium and in the territory of the town of Norcia»

[In the original French text: «Et premierement, diray du mont du lac de la royne sibille, que aucuns appellent le mont du lac de Pillate [...] parties de la duchié d'Espolit et ou terrouer de la cite de Norse»].

Because the Lake was not a Pilate's Lake, but a Lake of the Sibyl, or a Lake of Norcia, as also reported by Petrus Berchorius in his fourteenth-century “Reductorium Morale”. The Lake and Cave in the Sibillini Mountain Range are not distinct, they are part of a same legendary tale.

So we have a lake and a cave in Cumae, a lake and a cave in Ireland, and a further Lake and Cave in the territory of Norcia, amid the Sibillini Mountain Range: each pair of geographical landmarks being a part of a same local legendary framework.

The many similarities which are manifestly found among the three sites, all including a lake and a cave and a local otherwordly tradition, fostered many narrative contaminations, mainly from the two most famous ones to the less known Apennine site. Across many centuries, local residents, wayfarers, oral storytellers and men of letters spread the word about this amazing Lake and Cave concealed amid the ridges of the central Apennines, in Italy, by adding to their wondrous accounts a number of narrative elements taken from the famed legendary tales of the Cumaean Sibyl and St. Patrick's Purgatory, also marked by lakes and caves. Thus, the lore concerning the Lake and Cave set amid the Apennines was increasingly enriched with the inclusion of otherwordly elements which were typically contained in the most renowned accounts about Cumae and Lough Derg, like the 'test bridge' or the ever-slamming metal barriers.

In our present age, the establishment of any sort of connection between Cumae, Lough Derg and the Sibillini Mountain Range, though limited to a mere narrative level, might appear as a bold and basically unfounded conjecture. But this only happens because it is hard today to discern any link between the three different legendary traditions, which belong to territories that are different altogether and far from each other. And yet, the connection becomes utterly apparent not only when we confront with the literary witnesses which are available to us, but also if we are able to effectively put ourselves in the shoes of a man of the Middle Ages: at that time, the legendary tales about Cumae and the Purgatory of St. Patrick were well known to people, as the former was part of Vergil's “Aeneid”, a renowned classical literary masterwork, and the latter was included in Jacobus de Varagine's “Legenda Aurea”, a 'best seller' of its age. Thus, lakes and caves with an otherwordly character were part of on established, accepted classical and medieval lore: any further Lake and Cave featuring such a character would have immediately been put in relation with the two most famous legendary accounts, in a ceaseless and wide-reaching flow of oral narratives circulating throughout the whole of Europe across the centuries.

Certainly, the medieval readers of “Guerrino the Wretch” and “The Paradise of Queen Sibyl” could not restrain themselves from thinking about the Cumaean Hades or the Irish Purgatory, as the Apennine story contained too many patent affinities with the two illustrious legendary tales. Affinities that the men of the Middle Ages could easily discern.

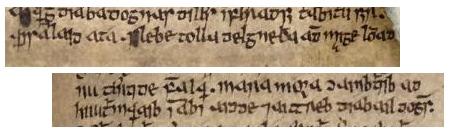

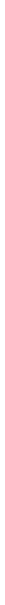

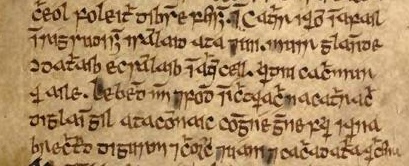

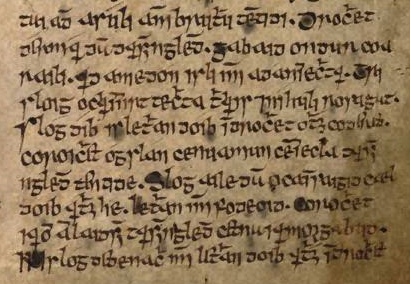

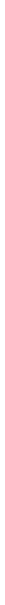

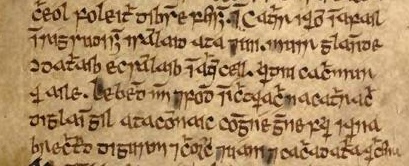

On the other side, even the Apennines were not totally unknown to the Irishmen of the Middle Ages, isolated as they were. In a fine thirteenth-century map of Europe contained in a precious manuscripted witness of Gerald of Wales' works "Topographia Hibernica" and "Expugnatio Hibernica" (MS 700, National Library of Ireland, Dublin) we find, in a same diagram drawn by an Irish hand, both Ireland and the Italian Apennines, a sign of some sort of mutual awareness, at least at a basical narrative level (Fig. 5).

So, we must consider the existence of a narrative connection between Cumae, Lough Derg and the Sibillini Mountain Range as a reasonable fact. The nature of this connection is merely narrative, as no actual, specific historical link has ever existed between the Sibyl's Cave and the Lake of Pilate, on one side, and the legendary tales concerning Cumae and the Purgatory of St. Patrick, on the other. The three sites were too far from each other to develop any common, coordinated legendary framework. Their respective lores were totally independent from one another. Just an overall affinity, though patently manifest, linked the three places together: presence of a lake, presence of a cave, and the existence of a legendary physical passageway to an Otherworld, which attracted visitors, be they pilgrims or necromancers.

Certainly, after decades of scientific and philological research, today we know many things about Lake Avernus and Lough Derg, with their respective caves: we know a lot about the legendary tales which concern the Cumaean Sibyl and the Purgatory of St. Patrick.

But still we know nothing about the Lake and Cave nested amid the central Apennines, in Italy.

Why should this Apennine site have been considered as a further entryway to the Otherworld?

And, if our assumptions are all true, what sort of Otherworld was this?

All the clues seem to indicate that in this third, specific location of Europe, amid the Sibillini Mountain Range, by a Lake and a Cave, mortal beings like Aeneas, like Owein, may make an actual attempt to access a different world, normally forbidden to the living: a realm of dead souls, a kingdom which was set under the rule of non-human entitities, of a divine, terrifying nature. A chthonian, subterranean Otherworld.

At Cumae, men imagined dreams of a pagan afterlife inhabited by the shades of the dead. At St. Patrick's Purgatory, men fancied a dream of a Christian Hell full of demons and excruciated souls.

But what sort of dreadful dream did men conceive at the Lake and Cave set amid the mountains of the central Apennines?

We still don't know. And yet, we are now beginning to form a conjecture which concerns the potential reason for which a Lake and a Cave set amid the Sibillini Mountain Range, in Italy, were turned by men in antiquity into a possible, legendary passageway to the Otherworld.

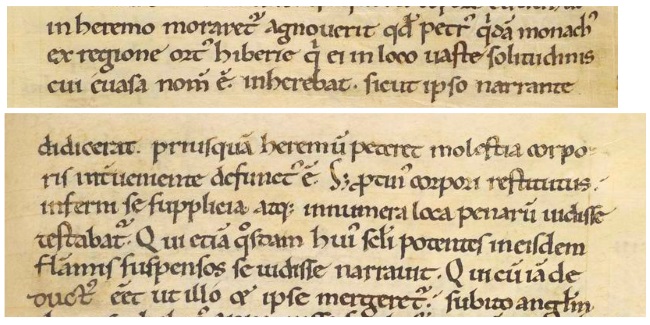

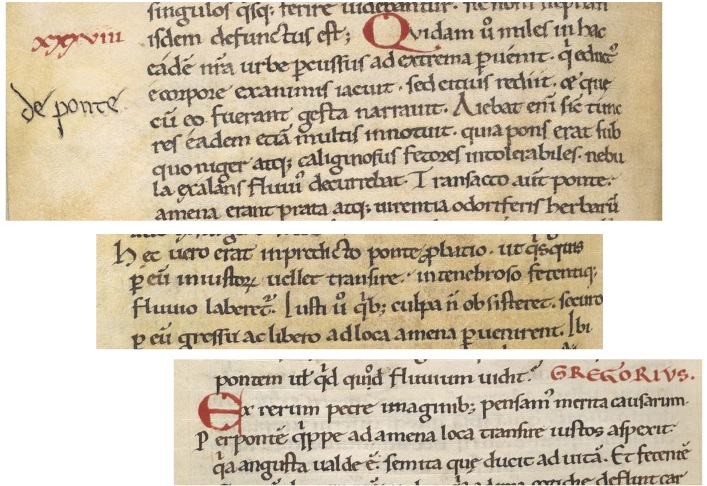

A passageway to some sort of demonic presence. An access that was to be unlocked by means of necromantic rituals. A point of contact with a subterranean Otherworld. A 'hot spot', a crevice drilled into the mountains to establish an appalling communication with the chthonian powers beneath. A break in the continuum of our ordinary world, not unlike the ghastly gap portrayed in 1346 by Jacopo di Mino del Pellicciaio in his fresco “The Purgatory of St. Patrick” at the convent of San Francesco al Borgo Nuovo at Todi, providing an access to a forbidden, inhuman realm (Fig. 6).

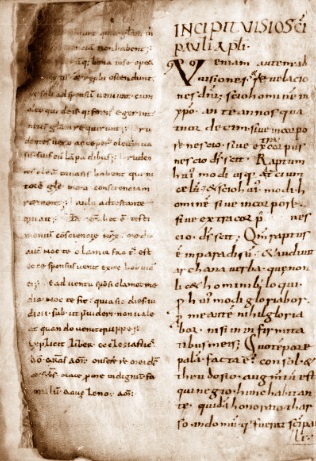

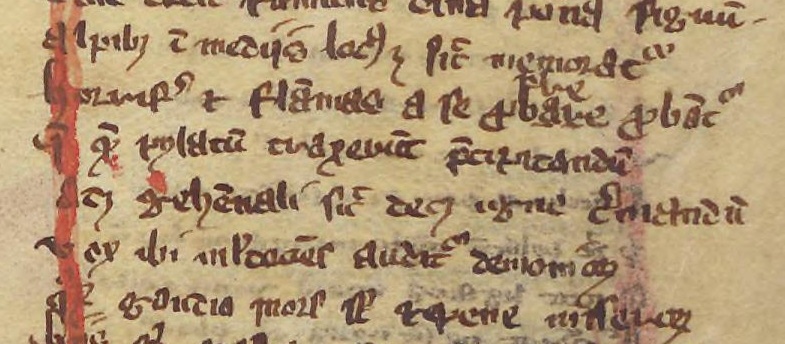

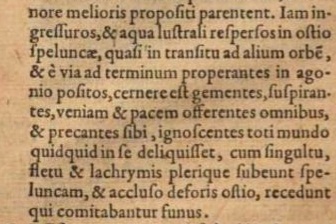

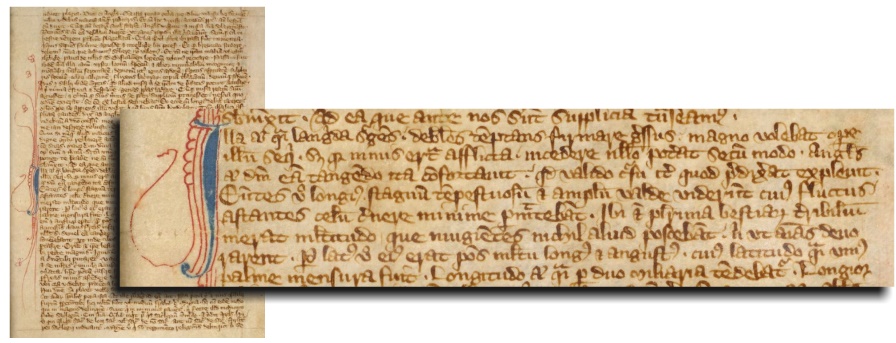

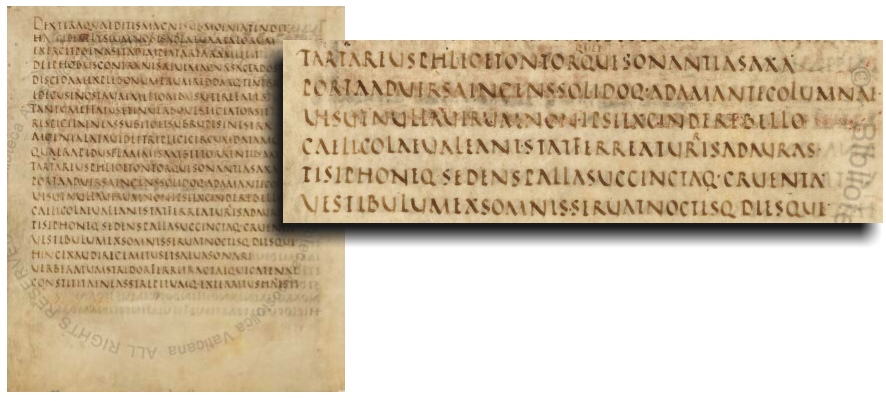

«Descendunt in infernum viventes»: «they descend alive into Hell», so wrote Petrus Berchorius in his fourteenth-century “Reductorium Morale", quoting from the Book of Psalms (55:15). He was writing about the Lake of Norcia, in the Sibillini Mountain Range (Fig. 7).

So, an access to an Otherworld at the Sibyl's Cave and the Lake of Pilate may have existed in an antique legendary tradition, though possibly different from the afterlives which were reputed to be accessible by men from Cumae and Lough Derg; and yet similar enough as to attract an uninterrupted flow of visitors to a remote, isolated, outlandish site for many centuries, the way it occurred at St. Patrick's Purgatory, too, though on a much significant scale.

A new supposition. A new theory. A legendary credence concerning an entryway to a mythical Otherworld in central Italy. One of a most terrific, dreadful sort. A crevice in our world, opened in the mountainous ridges - as we will se in our next and last article, still to be released - out of sheer terror. Terror for one own's life. Terror for the fate of one's family. Terror for the ruin of one's land.

With the next - and final - article on the legendary tales of the Sibillini Mountain Range, we will carry out an extraordinary, frightful journey through this new assumption.

And, in doing this, we will explore the deepest fears of human soul.

Monti Sibillini, un Lago e una Grotta come accesso oltremondano /5. Oltre le sovrapposizioni leggendarie, un passaggio ctonio tra gli Appennini centrali

Al termine del nostro emozionante viaggio attraverso il carattere oltremondano delle leggende della Grotta della Sibilla e del Lago di Pilato, situati nel massiccio dei Monti Sibillini, in Italia, proviamo a ricapitolare le nostre straordinarie scoperte e le ardite, potenzialmente significative ipotesi da noi enunciate a proposito della sussistenza di un leggendario punto di passaggio oltremondano che potrebbe essere stato posizionato, secondo una tradizione assai antica che avrebbe lasciato alcune deboli tracce nella letteratura a noi nota, proprio tra i picchi dell'Appennino centrale.

Per secoli, tra le creste e i precipizi dei Monti Sibillini, nell'Italia centrale, due rinomate leggende hanno raccontato storie meravigliose ai cuori degli uomini, che lì si recavano da ogni parte d'Europa: la Grotta della Sibilla, situata sulla cima di un picco coronato; e, solamente a pochi chilometri di distanza, il Lago di Pilato, circondato da formidabili e precipiti mura di roccia verticale. Si credeva che una sensuale Sibilla dimorasse in una Grotta nascosta al di sotto della montagna, in un regno sotterraneo abitato da leggiadre damigelle dalla demoniaca natura (Fig. 1). Si riteneva, inoltre, che un prefetto romano, quello stesso funzionario che aveva condannato Gesù Cristo alla morte sulla Croce, fosse stato gettato nelle acque gelide di quel Lago, il suo cadavere fatto oggetto di maledizione, come se si fosse trattato di una delle membra stesse del corpo del Demonio (Fig. 2). Due autori quattrocenteschi, Andrea da Barberino e Antoine de la Sale, scrissero opere letterarie che menzionavano le due leggende. E la fama dei due siti era corsa veloce tra le nazioni per centinaia di anni.

Eppure, qualcosa sembra non tornare.

Come abbiamo avuto modo di discutere in numerosi articoli di ricerca, precedentemente pubblicati, c'è qualcosa di sbagliato nel complesso sistema leggendario comunemente accettato: una Sibilla, forse la Cumana; Ponzio Pilato e il suo tragico destino; secoli e secoli di visite effettuate presso questi due siti, così isolati e quasi irraggiungibili.

Uno studio dettagliato delle due narrazioni leggendarie mostra chiaramente come la Sibilla Appenninica non appartenga alla famiglia degli oracoli classici, ma sia invece una discendente di Morgana la Fata e della sua negromantica compagna Sebile, due personaggi che fanno parte della Materia di Bretagna e del ciclo arturiano, posti in scena in molteplici romanzi e poemi cavallereschi scritti vari secoli prima, in un contesto letterario nordeuropeo. Un'ulteriore analisi dei racconti protocristiani e medievali concernenti Ponzio Pilato mostra come i suoi numerosi luoghi di sepoltura, situati in differenti regioni d'Europa, non abbiano nulla a che fare con gli Appennini italiani.

Così, secondo la nostra visione e a valle delle risultanze delle ricerche da noi già pubblicate, possiamo convintamente ipotizzare come nessuna Sibilla abbia mai potuto dimorare tra i picchi dei Monti Sibillini. E nessun Ponzio Pilato sia mai stato gettato in alcun lago dell'Italia centrale. Le due narrazioni non appartengono a questo lembo di terra italiana. Le due famose leggende non sono originali. Ambedue sono giunte qui provenendo da territori assai distanti.

Ma perché esse sono venute a stabilirsi proprio qui?

Se ci disponiamo a rimuovere i due citati livelli letterari, che dobbiamo ormai considerare come strati leggendari aggiuntivi, e iniziamo ad analizzare in dettaglio i sottostanti aspetti che caratterizzano le leggende che segnano i due siti, la Grotta e il Lago posti tra i Monti Sibillini, ci imbattiamo in una varietà di tratti comuni: pratiche negromantiche sono state effettuate in entrambi i luoghi; si riteneva che i due siti ospitassero leggendari demoni; tempeste e devastazioni si sarebbero prodotte a seguito dei proibiti rituali praticati dai negromanti.

Qualcosa si trovava già lì. Qualcosa che non aveva nulla a che fare con alcuna Sibilla, né con alcun antico prefetto romano. Qualcosa che sembrava esistere prima che lì si stabilissero i due livelli leggendari estranei e addizionali.

Siamo convinti che il percorso corretto da intraprendere, se realmente si intende svelare il vero nucleo delle leggende che vivono tra i Monti Sibillini, conduca verso una parola molto specifica, e forse anche inattesa: Aldilà.

Aldilà: un antichissimo sogno, che gli uomini hanno sognato sin da età assai remote, in un perenne confronto con la vita e la morte, la finitezza e il divino, e, dopo l'ascesa del Cristianesimo, con le verità ultime concernenti la salvezza e la dannazione.

A un esame più ravvicinato, approfonditamente condotto nell'ambito della presente ricerca, i racconti leggendari relativi alla Grotta della Sibilla e al Lago di Pilato appaiono essere caratterizzati da una serie di elementi narrativi oltremondani. Nel resoconto vergato da Antoine de la Sale, un 'ponte del cimento' sovrannaturalmente sottile si protende attraverso uno spaventoso abisso, divenendo però più largo a mano a mano che si procede su di esso, una tipica invenzione risalente ai "Dialoghi" di Papa Gregorio Magno, e successivamente presente in molteplici scritti visionari medievali. Porte di metallo che battono magicamente giorno e notte, con moto martellante e perenne, risultano essere anch'esse presenti, un genere di meccanismo che è rinvenibile in precedenti opere letterarie cavalleresche, e che è connesso a descrizioni oltremondane contenute nell'"Eneide" e nel mito greco delle Simplegadi. Stanze di cristallo attendono il visitatore, un chiaro segno di un'ambientazione oltremondana. E il Lago è apertamente indicato, in un brano trecentesco tratto da Petrus Berchorius, come un ingresso infernale. Il Lago stesso è segnalato con il nome di 'Lago Averno' in un diagramma manoscritto databile al sedicesimo secolo, potendosi così rilevare una corrispondenza narrativa assai significativa con il notissimo punto di ingresso all'Ade, posto dalla classicità nel territorio di Cuma.

Un punto di ingresso verso l'Aldilà: sin da tempi antichissimi è stato questo l'empio anelito albergato dagli uomini nel proprio cuore. Un sogno, il desiderio di cogliere una visione della vita oltre la vita, la brama di poter stabilire un proibito contatto con il mondo dei morti, il tentativo di realizzare iniqui desideri. E una ricerca delle verità ultime ed estreme.

Nel presente articolo, abbiamo esplorato i numerosi esempi letterari, parte di una consolidata tradizione occidentale, che narrano leggendari racconti di punti di passaggio verso l'Aldilà, in forma di 'nekyia', l'evocazione delle ombre dei morti all'ingresso del regno oscuro, o di 'catabasi', un viaggio che conduce un uomo mortale attraverso un passaggio e all'interno di una regione di terrore. Sono questi gli agghiaccianti itinerari percorsi da eroi visionari nella letteratura oltremondana della cultura occidentale. Nell'antichità classica, si tratta di Ulisse e della sua visita all'Ade, seguito poi da Enea e dal suo viaggio nell'Averno, guidato dalla Sibilla Cumana. E, successivamente, le visioni della prima Cristianità: San Paolo e il suo visionario sogno dell'Inferno, Papa San Gregorio Magno con il suo soldato, il primo di una serie di cavalieri che viaggeranno nell'Aldilà. E ancora, l'Irlanda, con le sue descrizioni medievali di terrificanti itinerari compiuti tra gli atroci tormenti e le punizioni inflitte ai peccatori: la "Visione di Sant'Adamnán", la "Visione di Tnugdalus" e il "Purgatorio di San Patrizio".

Ma solamente due sono i viaggi da considerarsi come itinerari molto speciali, straordinari percorsi nell'Aldilà: sono quei viaggi che non sono compiuti per mezzo di una mera visione, ma nella realtà effettiva. Con il corpo vivente di un uomo.

Nella tradizione letteraria occidentale, due sono i luoghi più celebri a partire dai quali potere intraprendere un viaggio così raccapricciante. Due 'hot spot'. Due fenditure praticate nella continuità del nostro mondo ordinario. Due crepe, spaventosamente aperte verso visioni leggendarie, ma miticamente reali, di un mondo infero sotterraneo, ctonio.

Il primo luogo si trova a Cuma, presso il Lago d'Averno, nell'Italia meridionale. E il secondo è il Purgatorio di San Patrizio, a Lough Derg, nella Contea di Donegal, nell'Irlanda settentrionale.

Presso questi due siti, uomini viventi potevano essere così folli da tentare di attraversare le porte che mai devono essere oltrepassate. Due punti di passaggio verso l'Aldilà. Due ingressi verso una vita oltre la vita abitata da leggendarie potenze demoniache.

I due tradizionali punti di ingresso erano ampiamente noti, nei secoli del medioevo, in tutta Europa. Essi erano stati al centro di varie opere letterarie, dall'"Eneide" al "Tractatus de Purgatorio Sancti Patricii", fino alla "Legenda Aurea". I visitatori si avventuravano in viaggi particolarmente difficoltosi al fine di raggiungere quei luoghi, con l'obiettivo di vedere con i propri occhi, e attraversare, i punti di contatto tra due mondi, normalmente separati: il mondo dei vivi, e il regno dei morti.

Per una strana casualità, non dovuta ad alcuna specifica, rintracciabile motivazione, ambedue i siti erano indicati da una medesima coppia di punti di riferimento geografico: un lago e una grotta per entrambi, due elementi naturali che fissavano con precisione la posizione dei due luoghi sulla superficie della Terra, ed erano conosciuti come tali.

Perché proprio Cuma e Lough Derg? Perché questi passaggi oltremondani sono venuti a posizionarsi esattamente presso questi due luoghi? Caverne esistevano in Cuma, che erano riempite fino alle volte da gas mefitici, capaci di indurre sogni, e talvolta anche un'orribile morte. Una grotta era presente anche a Lough Derg: entrando in essa, il sonno travolgeva i già esausti pellegrini, un sonno che generava sogni e incubi, a motivo, forse, della mancanza di aria respirabile e anche, è possibile tentare di ipotizzare, a causa delle presenza di gas velenosi che filtravano dalle paludi torbose.

Il Lago d'Averno e la sua grotta, a Cuma. Lough Derg e un'altra grotta, in Irlanda. Ma un'altra coppia di punti di riferimento geografico, costituita ancora da un Lago e da una Grotta, era presente nell'Italia centrale.

Si trattava della Grotta della Sibilla e del Lago di Pilato, posti tra i Monti Sibillini. Separati da una distanza pari a pochi chilometri (Fig. 3).

La medesima configurazione geografica, come a Cuma e a Lough Derg. Una presenza demoniaca rilevata e rituali negromantici effettuati anche presso questo terzo sito, in Italia. Caratteri oltremondani, che segnavano anche questi due luoghi nascosti tra gli Appennini.

E possiamo anche spingerci fino a ipotizzare che, nei secoli che precedettero il quindicesimo, quando le narrazioni erano solamente orali e le immagini fotografiche appartenevano a un futuro distante ancora molti secoli, la Grotta della Sibilla e il Lago di Pilato fossero fondamentalmente così vicini da potere essere considerati come un singolo sistema leggendario, in assenza della differenziazione della quale troviamo oggi traccia nelle loro diverse intitolazioni, alla Sibilla e a Pilato. Ed è lo stesso Antoine de la Sale a indirizzare la nostra ricerca in questa direzione, quando l'autore provenzale pone sulla pergamena le seguenti parole, all'inizio della propria opera "Il Paradiso della Regina Sibilla" (Fig. 4):

«Per prima cosa vi narrerò del monte del lago della Regina Sibilla, che è chiamato da alcuni il monte del lago di Pilato [...] parte del Ducato di Spoleto nel territorio della città di Norcia».

[Nel testo originale francese: «Et premierement, diray du mont du lac de la royne sibille, que aucuns appellent le mont du lac de Pillate [...] parties de la duchié d'Espolit et ou terrouer de la cite de Norse»].

Perché quel Lago non era un Lago di Pilato, ma un Lago della Sibilla, o anche un Lago di Norcia, così come riferito da Petrus Berchorius nel suo trecentesco "Reductorium Morale". Il Lago e la Grotta nei Monti Sibillini non sono entità differenti, ma sono parte di uno stesso racconto leggendario.

E così abbiamo un lago e una grotta a Cuma, un lago e una grotta in Irlanda, e un ulteriore Lago e un'altra Grotta nel territorio di Norcia, tra i Monti Sibillini, con ogni coppia di punti di riferimento geografico facente parte di uno stesso sistema leggendario locale.

Le molte analogie che sono manifestamente rinvenibili tra i tre differenti siti, tutti comprendenti un lago e una grotta e una tradizione oltremondana locale, hanno favorito molte contaminazioni narrative, principalmente a partire dai due luoghi maggiormente famosi in direzione del meno noto sito appenninico. Attraverso molti secoli, residenti del luogo, viandanti, cantastorie e uomini di lettere hanno contribuito a spargere la voce a proposito dell'esistenza di questo straordinario Lago e della vicina Grotta, occultati tra le creste dell'Appennino centrale, in Italia, aggiungendo ai propri meravigliosi racconti una molteplicità di elementi narrativi tratti dalle rinomate narrazioni leggendarie relative alla Sibilla Cumana e al Purgatorio di San Patrizio, anch'essi segnati dalla presenza di laghi e grotte. E così, la tradizione relativa al Lago e alla Grotta posti tra gli Appennini si trovò a esperimentare un progressivo arricchimento tramite l'inclusione di elementi oltremondani che facevano tipicamente parte dei celeberrimi racconti concernenti Cuma e Lough Derg, come il 'ponte del cimento' o le barriere di metallo eternamente battenti.

Nella nostra epoca contemporanea, l'individuazione di qualsivoglia genere di connessione tra Cuma, Lough Derg e i Monti Sibillini, benché limitata a un mero livello narrativo, potrebbe apparire come una congettura ardita e sostanzialmente infondata. Ma questo accade solamente perché oggi è difficile discernere un collegamento tra le tre differenti tradizioni leggendarie, appartenenti a territori diversi tra loro e mutuamente assai distanti. Malgrado ciò, queste connessioni diventano assolutamente palesi non solo quando ci si confronti con le testimonianze letterarie che sono giunte fino a noi, ma anche se siamo capaci di metterci nei panni dell'uomo del medioevo: a quel tempo, i racconti leggendari relativi a Cuma e al Purgatorio di San Patrizio erano ben noti, essendo il primo contenuto nell'Eneide virigiliana, un insigne capolavoro letterario classico, ed essendo il secondo incluso nella "Legenda Aurea" di Jacopo da Varagine, un 'best seller' della propria epoca. Dunque, laghi e grotte caratterizzati da aspetti oltremondani facevano parte di una tradizione stabilita e accettata, sia classica che medievale: ogni ulteriore Lago e ogni ulteriore Grotta segnata da caratteri simili sarebbe stata immediatamente posta in relazione con i due famosissimi racconti leggendari, in un incessante ed estesissimo flusso di narrazioni orali circolante attraverso i secoli e capace di percorrere l'intera Europa.

Certamente, i lettori medievali del "Guerrin Meschino" o del "Paradiso della Regina Sibilla" non potevano evitare di correre con il pensiero all'Ade cumano o al Purgatorio irlandese, in quanto la storia appenninica conteneva troppe manifeste affinità con i due illustri racconti leggendari. Affinità che gli uomini del medioevo erano facilmente in grado di riconoscere.

Dall'altro lato, anche gli Appennini non risultavano essere totalmente sconosciuti all'uomo irlandese del medioevo, per quanto isolato egli fosse. In una affascinante mappa dell'Europa contenuta in un prezioso esemplare maoscritto delle opere di Giraldus Cambrensis, "Topographia Hibernica" e "Expugnatio Hibernica" (MS 700, National Library of Ireland, Dublino), troviamo, in un medesimo diagramma tracciato da una mano irlandese, sia l'Irlanda che gli Appennini italiani, segno di una qualche sorte di mutua consapevolezza, quantomeno a un basilare livello narrativo (Fig. 5).

E dunque, dobbiamo considerare la sussistenza di una connessione narrativa tra Cuma, Lough Derg e i Monti Sibillini con un fatto del tutto ragionevole. La natura di tale connessione è puramente narrativa, poiché nessun effettivo legame storico è mai esistito tra la Grotta della Sibilla e il Lago di Pilato, da un lato, e i racconti leggendari relativi a Cuma e al Purgatorio di San Patrizio, dall'altro. I tre siti erano collocati in luoghi troppo distanti tra di loro per potere sviluppare qualsivoglia struttura leggendaria mutuamente coordinata. Le rispettive tradizioni erano del tutto indipendenti l'una dall'altra. Solamente una generale affinità, per quanto chiaramente manifesta, connetteva tra di loro i tre luoghi: presenza di un lago, presenza di una grotta, e esistenza di un leggendario punto di passaggio fisico verso un Aldilà, capace di attirare flussi di visitatori, sia che si trattasse di pellegrini oppure di negromanti.

Di certo, dopo decine e decine di anni di ricerca scientifica e filologica, conosciamo molte cose a proposito del Lago d'Averno e di Lough Derg, con le loro rispettive grotte: sappiamo molto dei racconti leggendari che riguardano la Sibilla Cumana e il Purgatorio di San Patrizio.

Eppure, non conosciamo ancora nulla a proposito del Lago e della Grotta annidati tra le vette dell'Appennino centrale, in Italia.

Perché questo sito appenninico avrebbe dovuto essere considerato come un ulteriore punto di ingresso all'Aldilà?

E, se le nostre supposizioni sono corrette, di quale genere di Aldilà si trattava?

Tutti gli indizi sembrano indicare come in questa terza, specifica località europea, tra i Monti Sibillini, presso un Lago e una Grotta, uomini mortali come Enea, come Owein, abbiano potuto effettuare un tentativo, reale ed effettivo, di accedere a un mondo differente, normalmente interdetto ai viventi: un regno di anime prive di vita, una landa che era posta sotto il controllo di entità non umane, dalla natura terrificante e divina. Un Aldilà ctonio, sotterraneo.

A Cuma, gli uomini immaginarono sogni di un oltretomba pagano abitato dalle ombre dei morti. Presso il Purgatorio di San Patrizio, altri uomini fantasticarono di un inferno cristiano pullulante di demoni e di anime tormentate.

Ma quale sorta di terrificante sogno fu concepito dagli uomini presso il Lago e la Grotta posti tra le montagne dell'Appennino centrale?

Non lo sappiamo ancora. Eppure, stiamo cominciando a formulare una congettura che è relativa alle potenziali ragioni per le quali un Lago e una Grotta situati tra i Monti Sibillini, in Italia, siano stati trasformati dagli uomini, nell'antichità, in un possibile, leggendario passaggio verso l'Aldilà.

Un punto di passaggio verso una qualche tipologia di demoniaca presenza. Un accesso che andava dischiuso utilizzando opportuni rituali negromantici. Un punto di contatto con un Aldilà sotterraneo. Un 'hot spot', una frattura scavata nelle montagne allo scopo di stabilire una spaventosa comunicazione con i poteri ctonii nascosti nel sottosuolo. Un'interruzione nel continuum del nostro mondo ordinario, non diverso dall'agghiacciante varco rappresentato nel 1346 da Jacopo di Mino del Pellicciaio nel suo affresco "Il Purgatorio di San Patrizio", realizzato all'interno del convento di San Francesco al Borgo Nuovo a Todi (Fig. 6).

«Descendunt in infernum viventes»: «discendono vivi all'Inferno», così aveva scritto Petrus Berchorius nel suo trecentesco "Reductorium Morale", citando dal Libro dei Salmi (55:15). Egli scriveva a proposito del Lago di Norcia, situato tra i Monti Sibillini (Fig. 7).

Dunque, un accesso a un Aldilà localizzato presso la Grotta della Sibilla e il Lago di Pilato è forse esistito secondo un'antica tradizione leggendaria, benché in modo forse differente rispetto alla vita oltre la vita che si riteneva potesse essere accessibile da Cuma e Lough Derg. Ma, comunque, sufficientemente simile da attrarre un flusso ininterrotto di visitatori, per molti secoli, fino a quel sito remoto, così isolato e difficoltoso da raggiungere, così come accadeva anche presso il Purgatorio di San Patrizio, anche se su una scala molto più significativa.

Una nuova ipotesi. Una nuova teoria. Una credenza leggendaria relativa a un punto di ingresso verso un mitico Aldilà, situato nell'Italia centrale. Di un genere particolarmente spaventoso, terrificante. Una fenditura nel nostro mondo, aperta tra le creste montuose - come avremo modo di vedere nella nostra prossima e ultima ricerca, che sarà pubblicata a breve - sulla spinta di un terrore puro e ancestrale. Terrore per la propria vita. Terrore per il destino della propria famiglia. Terrore per la rovina della propria terra.

Con il prossimo - e conclusivo - articolo sui racconti leggendari che abitano i Monti Sibillini, effettueremo uno straordinario, spaventoso viaggio attraverso questa nuova ipotesi.

E, nel fare ciò, andremo a esplorare le più profonde paure che vivono nell'animo umano.

19 Feb 2020

Sibillini Mountain Range, a cave and lake to the Otherworld /4.4 Further mythical affinities: Lough Derg and the Sibillini Mountain Range

In the previous paragraphs, we illustrated the mythical tale of Cumae, featuring a Lake Avernus and a nearby cave which, in classical antiquity, was believed to provide an access to the Otherworld. We also highlighted the narrative connections that linked this Cumaean tale, widely known throughout Europe owing to its presence in Vergil's “Aeneid”, and the legends which inhabited the Sibillini Mountain Range, provided with its own Cave and Lake.

But affinities are not over. We also saw that a northern-European country, Ireland, housed another legendary tale: again, a lake, Lough Dergh, and a cave, which was the entryway to another Otherworld, the Purgatory of St. Patrick. And this tale, as well, was widely known throughout Europe, and also in the Italian peninsula and, specifically, as we will see later in this same article, in central Italy.

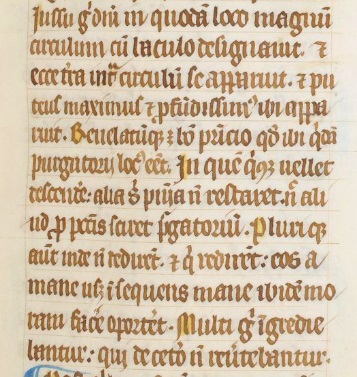

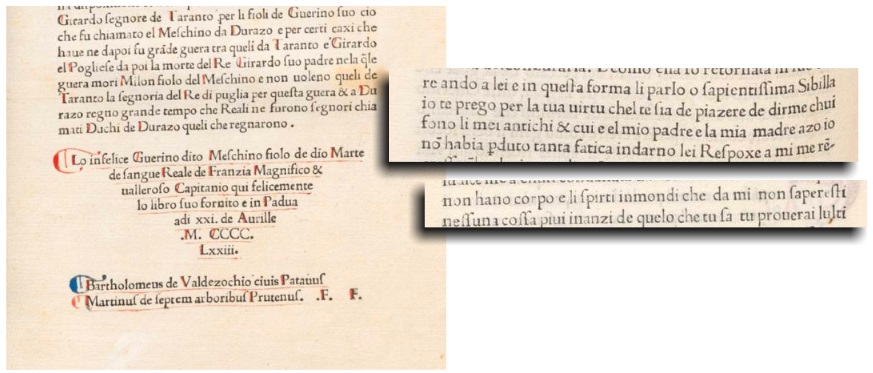

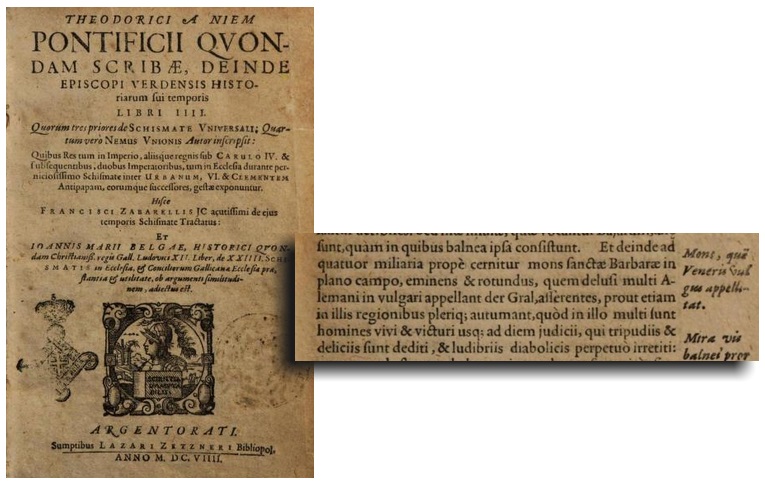

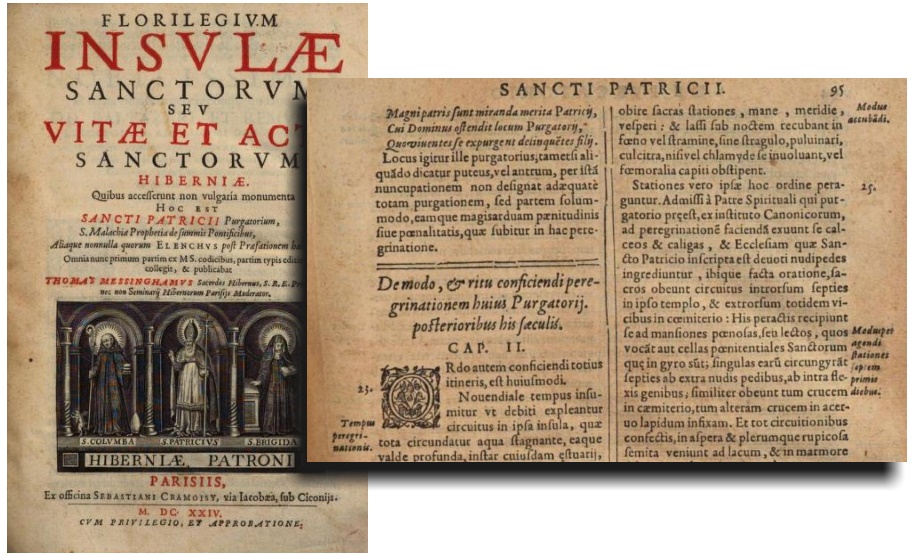

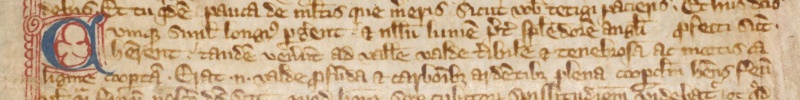

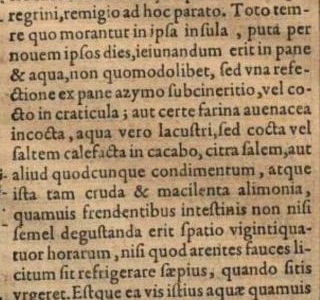

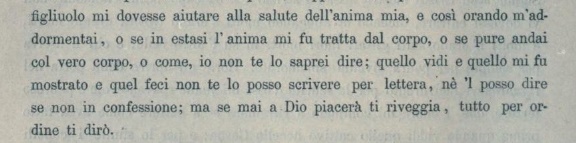

A most significant example of the widespread renown of the Purgatory of St. Patrick is provided by the “Legenda Aurea”, the collection of tales about the life and death of more than a hundred fifty saints which was written by Jacobus de Varagine, a Dominican friar and bishop from the Italian town of Genoa, in the second half of the thirteenth century.

The “Legenda Aurea” was a most successful work, a sort of 'best seller' for many centuries, with thousands of manuscripts still extant. It was considered by preachers as a convenient source of themes and topics, and was read by all sorts of audiences, owing to the fascinating stories it contained about the impressive, moving martyrdoms of holy men and women, and the overall readibility of the text, written in a simple, tough fluent, Latin.

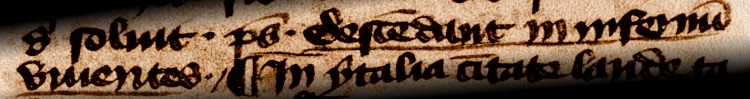

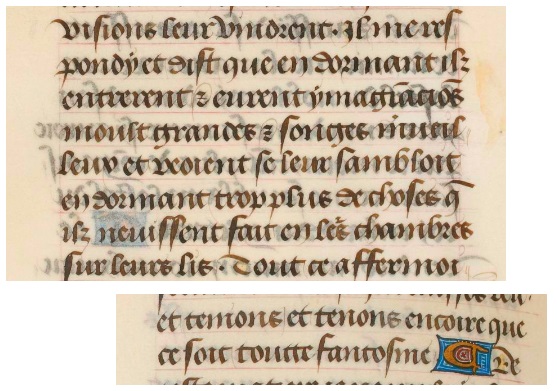

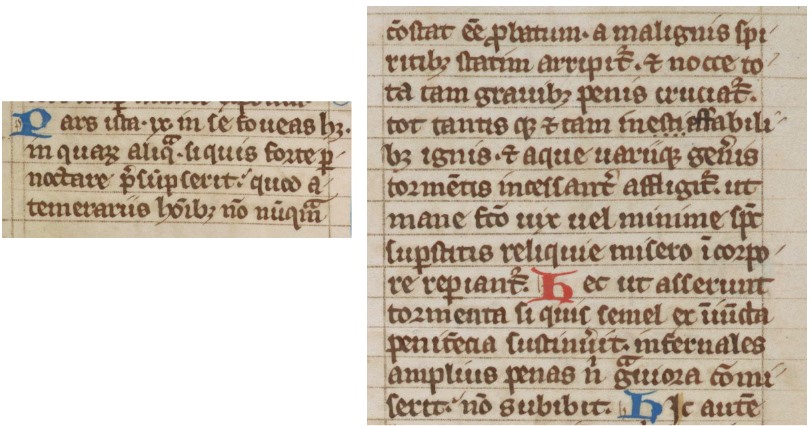

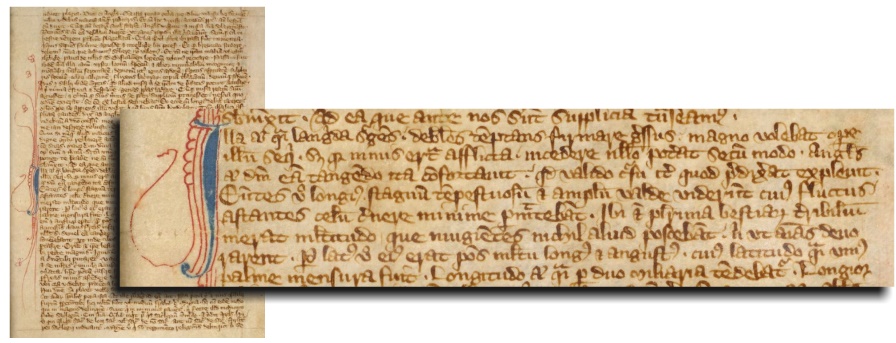

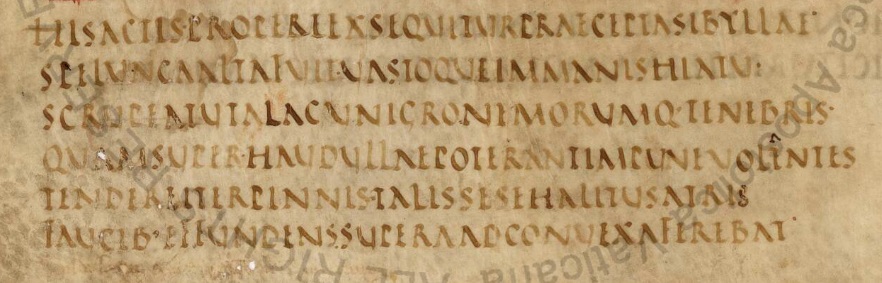

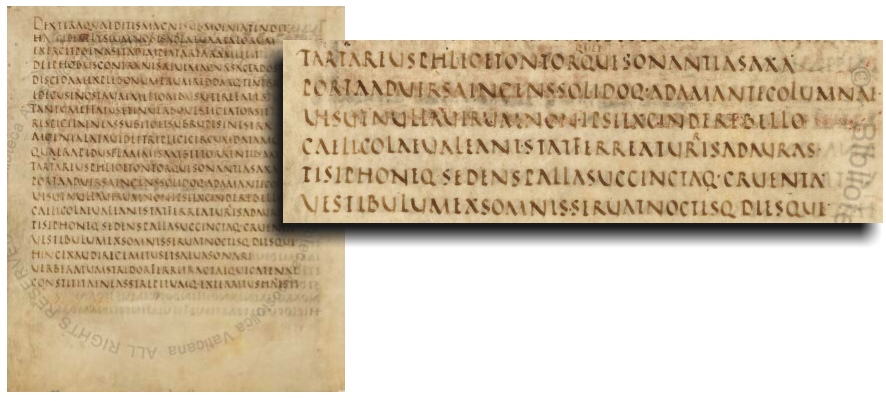

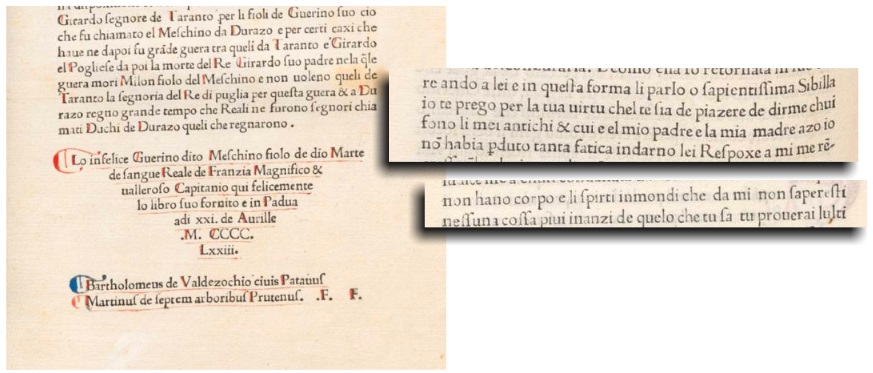

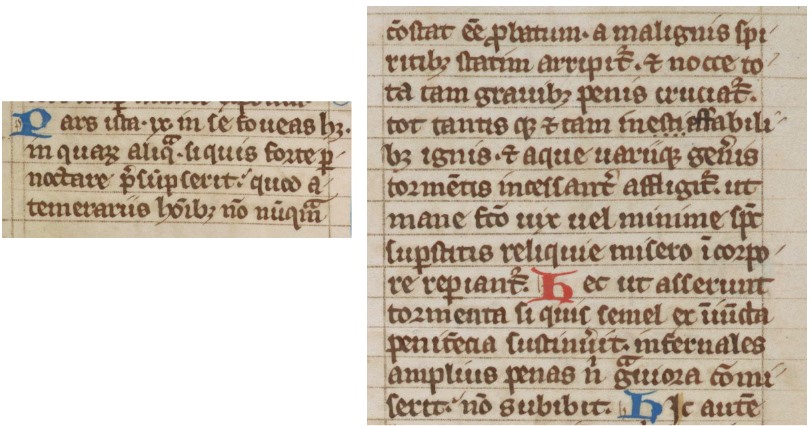

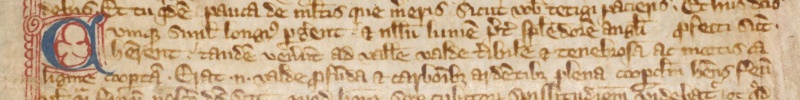

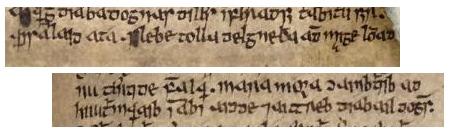

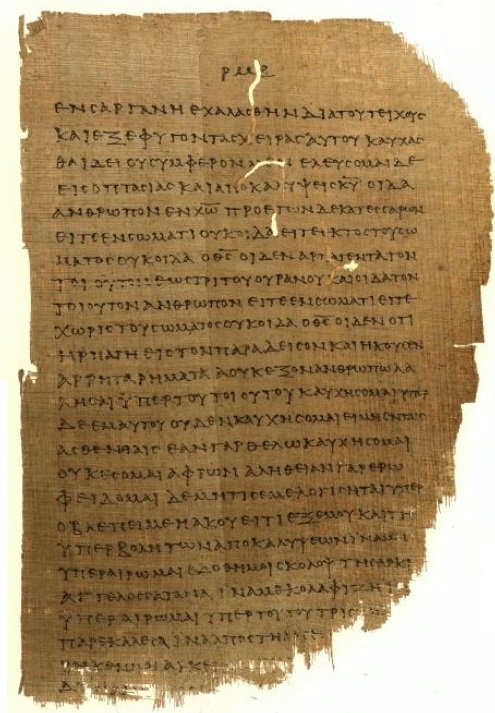

And the “Legenda Aurea”, in its Chapter XLIX, which immediately followed the section dedicated to a most venerated saint, Benedict of Norcia, did not overlook the Purgatory of St. Patrick at all (Fig. 1 and 2):

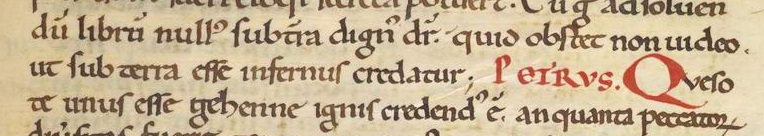

«The Lord commanded that he [St. Patrick] drew on a certain spot a large circle on the ground with his staff, and immediately the ground within the circle opened up and there appeared a pit of unfathomable depth; and it was revealed to St. Patrick that there was the entrance to the Purgatory; whoever entered therein he should never suffer other punishments, nor experience the purgatory out of his sins. Many should never return from it, and those who come back should stay in it no more than one single day. And many entered that came not again».

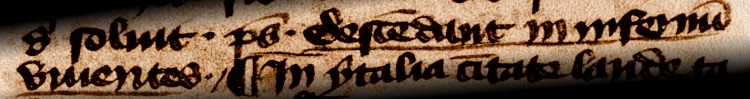

[In the original Latin text: «Jussu igitur domini in quodam loco magnum circulum cum baculo designavit et ecce terra inter circulum se aperuit et puteus maximus et profondissimus ibi apparuit revelatumque est beato Patricio, quod ibi purgatorii locus esset, in quem quisquis vellet descendere, alia sibi poenitentia non restaret nec aliud pro peccatis sentiret purgatorium, plerique autem indem non redirent et qui redirent eos a mane usque in sequens mane ibidem moram facere oporteret. Multi igitur ingrediebantur, qui de caetero non revertebantur»].

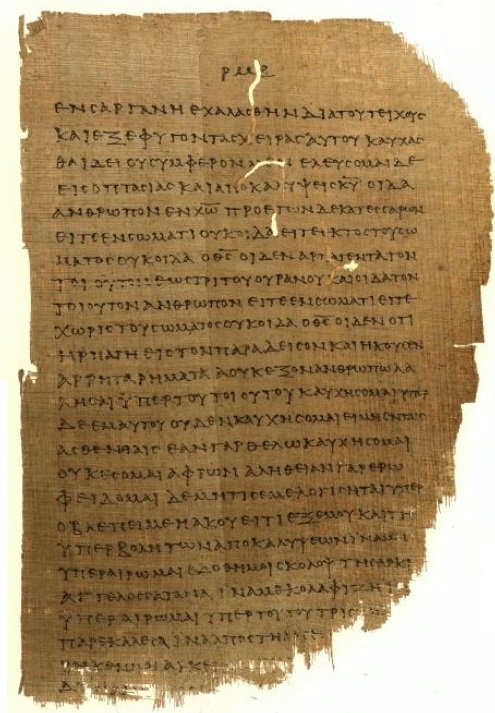

This is the description of the legend of St. Patrick's Purgatory as contained in the chapter dedicated to the Irish saint in the “Legenda Aurea”, a passage which is patently drawn from Henry of Saltrey's “Tractatus de Purgatorio Sancti Patricii”.

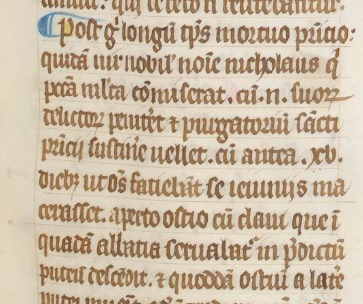

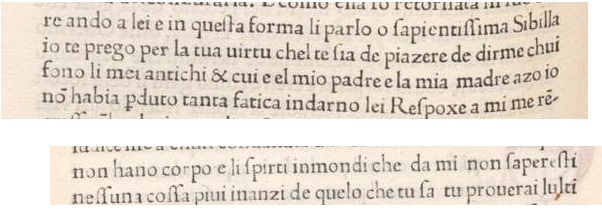

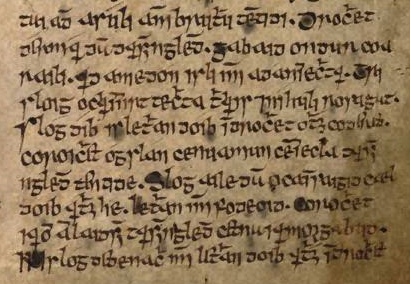

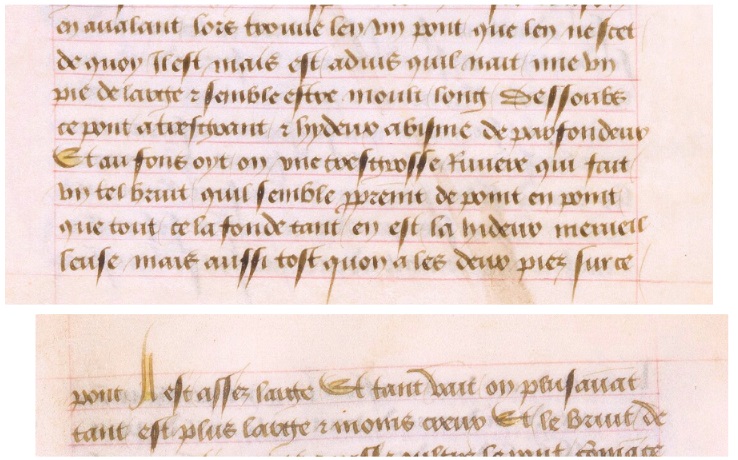

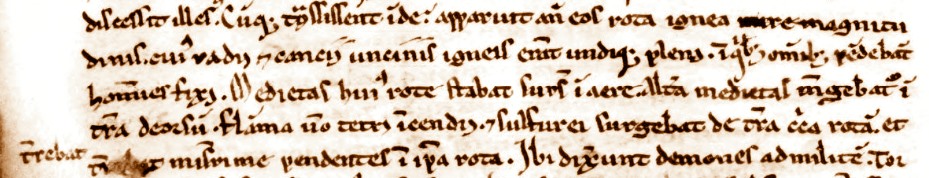

Jacobus de Varagine did not miss the chance to include in his own work the full story of the thrilling descent of Owein into the Purgatory of St. Patrick, so his account proceeds further, with a change in the name of the main character (Fig. 3):

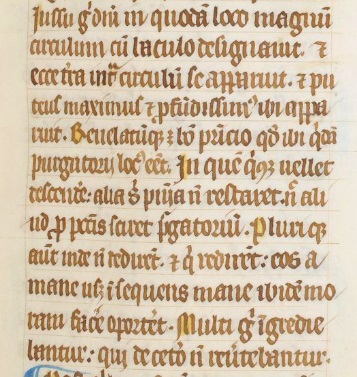

«A certain nobleman whose name was Nicholaus, who had committed many sins [...] decided to enter the Purgatory of St. Patrick. So he first exhausted himself by abstaining from food for fifteen days, as everybody used to do; then, the door was unlocked with the key that was preserved at the Abbey, and into the hollow he went...»

[In the original Latin text: «Quidam vir nobilis nomine Nicholaus, qui peccata multa commiserat [...] purgatorium sancti Patricii sustinere vellet, cum antea quindecim diebus, ut omnes faciebant, se ieiuniis macerasset, aperto ostio cum clavi, quae in quadam abbatia servabatur, in praedictum puteum descendit...»].

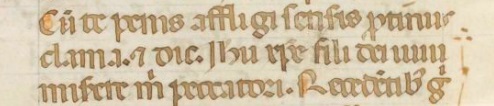

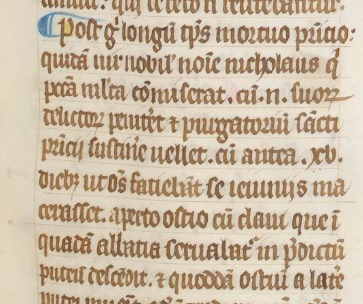

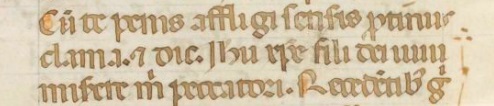

Then a long account of Nicholaus' travel into the Purgatory follows, similarly drawn from the work written by Henry of Saltrey. He meets the same men dressed in white, who advise him to invoke the name of Jesus when undergoing the Purgatory's excruciating tortures («cum te poenis affligi senseris, protinus clama et dic: 'Jesu Christe fili Dei vivi miserere mihi peccatori»), an appeal to which Guerrino the Wretch will often resort as well in the romance written by Andrea da Barberino (Fig. 4).

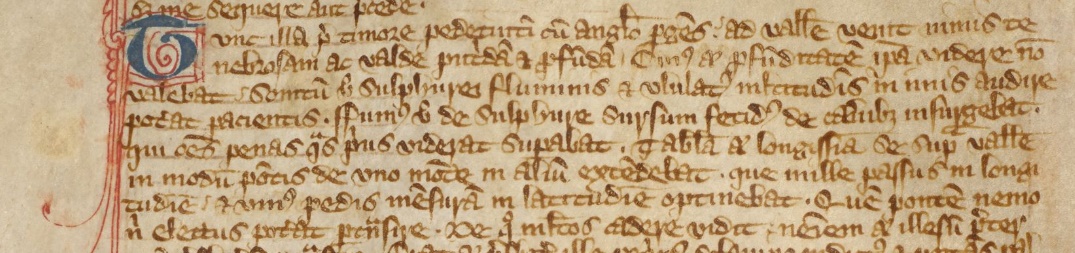

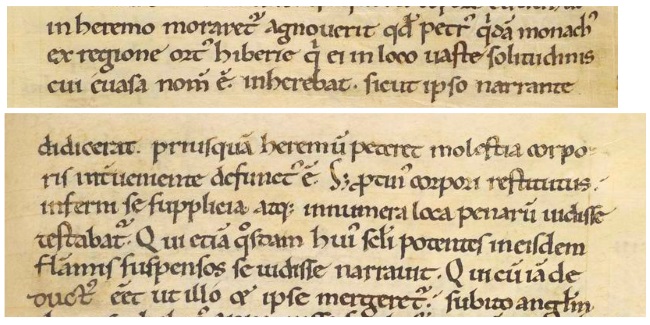

Then terrible purgatorial punishments begin to be presented to him by the demons. The usual visions of fire and hooks and fiendish whips which we already know from Henry of Saltrey, including the most famous wheel of fire («rota maxima erat uncinis ferreis ignitis plena...») are also described by Jacobus. And the “Legenda Aurea” does not forget to report about the well-known otherwordly 'test bridge' device, which, as we already know, we will also find in the Sibyl's Cave (Fig. 5):

«He was led to a place in which a bridge stood [...] that was utterly narrow and polished and slippery as ice; under the bridge a river of sulphureous fire was flowing, so that it seemed impossible to cross it [...] He confidently entered the bridge and put a foot on it, as he began to utter the words 'Jesus Christ etc.' [...] At each step he treaded, he pronounced these words and crossed safely».

[In the original Latin text: «Ductus igitur ad alium locum vidit quendam pontem [...] qui quidem erat strictissimus et instar glaciei politus et lubricus, sub quo fluvius ingens sulphureus et igneus fluebat, super quem dum se posse transire omnino desperaret [...] confidenter accessit et unum pedem super pontem ponens, Jesu Christe etc. dicere coepit [...] ad quemlibet passum eadem verba protulit et sic securus transivit»].

The amazing legend of the Purgatory of St. Patrick was fully known in Italy, with its cave described by Henry of Saltrey and its lake, mentioned by Gerald of Wales, and a thorough illustration elaborated by Jacobus de Varagine. And we can easily show that, in the fourteenth century, the legend was perfectly known in central Italy as well, in a place that was only 45 miles away from the Sibillini Mountain Range. In 1346, Jacopo di Mino del Pellicciaio, an artist from Siena, painted an astounding fresco on a wall of the refectory of the convent of San Francesco al Borgo Nuovo at Todi, Umbria. The fresco portrays exactly “The Purgatory of St. Patrick”: a remarkable witness to the success of the Irish legendary tale in a central-Italian cultural environment (Fig. 6).

A lake and a cave in Ireland, which provided a legendary entryway to an Otherworld. Another Lake and another Cave in central Italy, for which tales were told about necromancy and demons.

In a previous paragraph, we already noted that, in the Middle Ages, whoever had any memory of classical antiquity he would associate the site set amid the Apennines with Cumae, its lake and cave, and an ancient Sibyl.

But another narrative association was also possible.

Everybody knew of the medieval legend of the Purgatory of St. Patrick, too, with its lake and terrific cave. A legendary tale that was fully reported in the most-renowned and widely-read "Legenda Aurea". So, any eerie tale concerning a further Lake and Cave in the Apennines, marked by some magical or otherwordly characters, would immediately bring to the listener's mind that sinister, far-away Purgatory.

Oral storytellers and, later in time, men of letters could not keep away from incurring some sort of combination of the two mutually extraneous narratives: a lake and cave set in northern Ireland, and the Lake and Cave lying in a massif which is part of the Apennine mountainous chain. Precisely the same contamination process, wholly natural as a tale spreads amid audiences across the centuries, which led to a combination of the sibilline tale in the Apennines and the legend established in Cumae since classical antiquity.

So, once more, we find that the geographical landmarks set amid the Apennines generated an attractive pull for a different legendary tale, which in this case came from Ireland: and the result is the incorporation of themes and suggestions linked to the Purgatory of St. Patrick into the Sibillini Mountain Range's legendary tradition, despite its being set in a different territory altogether.

Again, the mythical tale of an otherwordly entryway accessible by men in Ireland experienced a partial migration to the area of the Sibillini Mountain Range, as oral storytellers added details and spice to their accounts concerning an icy Lake and a Cave set on a cliff, both lost in a secluded region of the Italian Apennines. Again. If a passageway to the afterlife existed in Ireland, this was to be considered as an occurrence, mythical as it was, which provided further strength to the Italian tale, out of an easily-noticeable similarity between the two locations, both marked by the presence of a lake and a cave.

Of course, the Purgatory of St. Patrick has nothing to do with the Apennines; nonetheless, their respective legendary narratives underwent some degree of combination, as already illustrated in our previous articles “St. Patrick's Purgatory, a source for Guerrino and Antoine de La Sale”, “Antoine de La Sale and the magical bridge concealed beneath Mount Sibyl” and “Birth of a Sibyl: the medieval connection”.

This process can be detected in both literary works which, in the fifteenth century, marked the starting point of the European-wide success of the legend of an Apennine Sibyl: Andrea da Barberino's romance “Guerrino the Wretch” and Antoine de la Sale's account “Paradise of Queen Sibyl”.

Needless to say, both authors had full acquaintance with the myth of Lough Derg and its Purgatory.

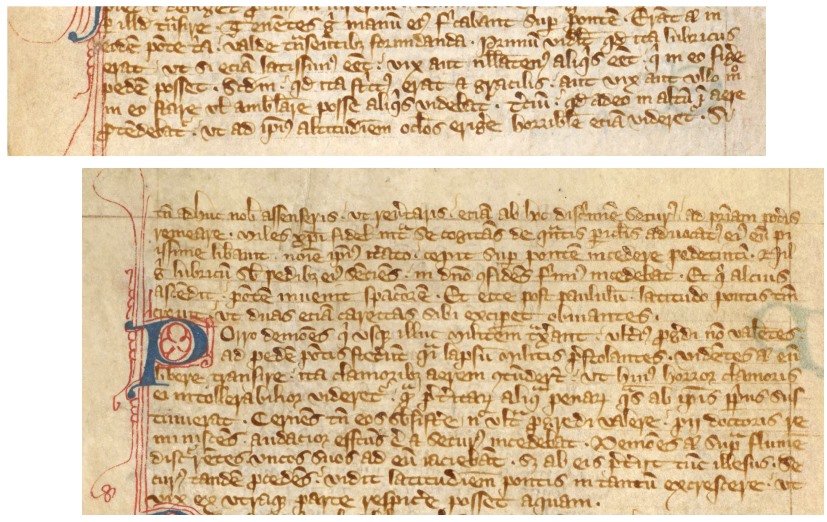

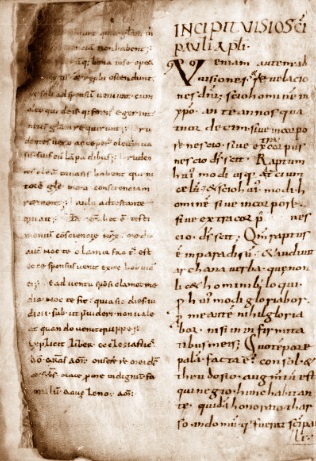

Antoine de la Sale clearly signals the above fact when, in his work “La Salade”, he includes a direct reference to the Irish legend of St. Patrick (Fig. 7):

«The isle of Ireland, very close to England, is wide and primitive, and the local people too. A church dedicated to St. Patrick is found there and there is also the cave in which people say that the punishments of Purgatory and the torments of Hell can be seen».

[In the original French text: «L'ysle de yrlande ioinct assez pres dangleterre est elle moult grande et sausvaige et les gens aussi leglise sainct Patrisse y est et la est la caue ou se dit que on va veoir les peines de purgatoire et les tourmens denfer»].

When Antoine de la Sale writes his account of his own visit to a Lake and a Cave in central Apennines, he introduces in his narration a few details which appear to be drawn from extraneous material concerning journeys to the Otherworld, with a specific reference to the legend he thoroughly knew, the Purgatory of St. Patrick, featuring its own lake and cave. And the first detail, as we already indicated at the beginning of the present research article, is the 'test bridge' (Fig. 8):

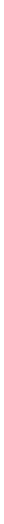

«Then you find a bridge, made of some unknown material, but it is said to be less than a single foot wide and it seems to be extending far ahead. Below the bridge, a ghastly, precipitating abyss [...] Yet as soon as you put both feet on the bridge, it becomes large enough; and the more you step ahead, the more it widens and the abyss becomes shallower».

[In the original French text: «Lors trouve-l'on un pont, que l'on ne scet de quoy il est, mais est advis qu'il n'ait mie un pied de large et semble estre moult long. Dessoubz ce pont, a très grant et hydeux abisme de parfondeur [...] Mais aussitost que on a les deux pieds sur ce pont, il est assez large; et tant vait on plus avant tant est plus large et moins creux»].

We know that the magically narrow bridge is present in many other otherwordly accounts, including St. Gregory the Great's "Dialogues", the “Vision of St. Adamnán” and the “Vision of Tnugdalus”; nonetheless, in the fifteenth century whoever read the words written by Antoine de la Sale would jump back, in his own mind, to the most famous and most impressive 'test bridge' of all its kindred, i.e. the one portrayed in Henry of Saltrey's “Tractatus de Purgatorio Sancti Patricii” and its subsequent description as reported by Jacobus de Varagine in his widely-known “Legenda Aurea”.

In addition to that, we also stumble upon an amazing pictorial contamination between the legend of St. Patrick's Purgatory and the description of the Sibyl's Cave as provided by Antoine de la Sale in his gorgeous illuminated account “The Paradise of Queen Sibyl”, which we find in manuscript no. 0653 (0924) preserved at the Bibliothèque du Château - Musée Condé in Chantilly, France.

At folium 9v, the French gentleman provides a portrait of himself on the top of Mount Sibyl as he enters the narrow passageway to the Cave (Fig. 9).

But a strikingly similar miniature is preserved in manuscript Français 1544, preserved at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and dating to at least fifty years earlier. At folium 105r, we find a pilgrim daringly entering the cave which leads into St. Patrick's Purgatory, at Lough Derg (Fig. 10).

And other comparable images are found in manuscript Additional 17275 preserved at the British Library in London: two miniatures associated to a French version of the “Golden Legend” and its description of St. Patrick's Purgatory, dating to the mid of the fourteenth century, a clear sign that the pictorial representations of the mythical Irish purgatorial access were markedly similar to the idea of an entryway to a magical or otherwordly realm set amid the Italian Apennines (Fig. 11).

A sort of representation we also find in later centuries, again in connection with St. Patrick's Purgatory and the “Legenda Aurea”, like the one we retrieve in manuscript no. 672-5 II preserved at the Morgan Library in New York (folium 178v), dating to the second half of the fifteenth century (Fig. 12).

We cannot tell whether Antoine de la Sale ever saw the versions in French of the legend of the Purgatory of St. Patrick contained in the two earlier manuscripts, the Français 1544 and the Additional 17275; however, it seems apparent that similarities between the Purgatory in Ireland and the Sibyl's Cave in Italy do exist in terms of narrative choices that Antoine de la Sale made when editing his account concerning a visit to an entryway to a fiendish realm hidden amid the Italian Apennines. For we must be aware, as we already pointed out in our previous article “Sibillini Mountain Range: the legend before the legends”, that Antoine de la Sale considered the Italian Cave as an evil place inhabited by a «fake Sibyl» («faulse Sibille») of demonic origin, in which men confronted with «all wraiths and Devil's contrivances [...] through which the demons used to deceive people» («toutes fantosmes et toutes deableries [...] de quoy les deables decevoient le gens»). A demonic place which housed wicked demons, not unlike the Irish Purgatory.

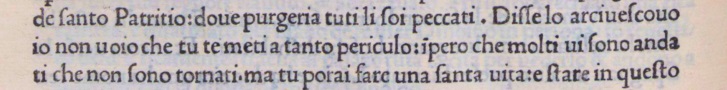

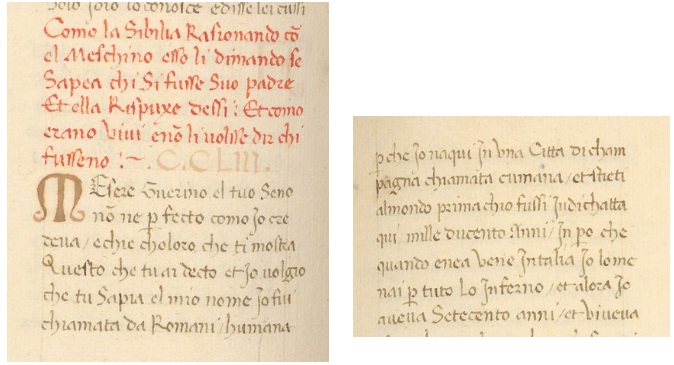

If we now come to Andrea da Barberino, we stumble upon further conections and similarities. The Italian writer proves to be far more straight than Antoine de la Sale was. His reference to the Purgatory of St. Patrick is so patent and extended that we cannot fail to miss it when we read his romance “Guerrino the Wretch”.

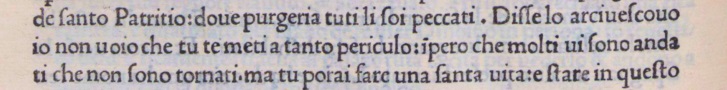

At the very end of the section dedicated to the Sibyl, Andrea da Barberino sends his knight hero, Guerrino, right into the Purgatory of St. Patrick, in Ireland, as a penitence imparted to him by the Pope for having been at the forbidden court of the Apennine Sibyl (Fig. 12):

«The Holy Father spoke to him: 'You are blessed' [...] and, as a penitence, he commanded to him, the way he had dared violate God's edict not to enter the abode of the Sibyl and visit illusory idols, to go to the Purgatory of St. Patrick, which is under the rule of the Archbishop of Hibernia in the island called Ireland».

[In the original Italian text: «El santo padre li disse: 'tu sei benedetto" [...] e per penitenzia impose como lui havea havuto ardire contra el comandamento de la leze de dio de intrare dove stava la Sibilla et de andare a visitare li idoli [...] chusì volea che per comandamento lui andasse a lo purgatorio de santo Patritio el quale è sotto l'arcivescovo de Ibernia in l'ixola dita Irlanda»].

The journey of Guerrino into the Irish Purgatory immediately follows his stay at the Sibyl's subterranean realm, the former being a penance imparted to the knight for having visited the latter: a sign that a narrative connection exists in Andrea da Barberino's mind, with the demonic presence at the Sibyl's Cave linked with the demons which inhabit the purgatorial cavern, out of a common otherwordly character. We will also see that the very same uttering of the name of Jesus Christ will dispel the demonic powers present at both caves, another token of the common narrative traits that link the two episodes.

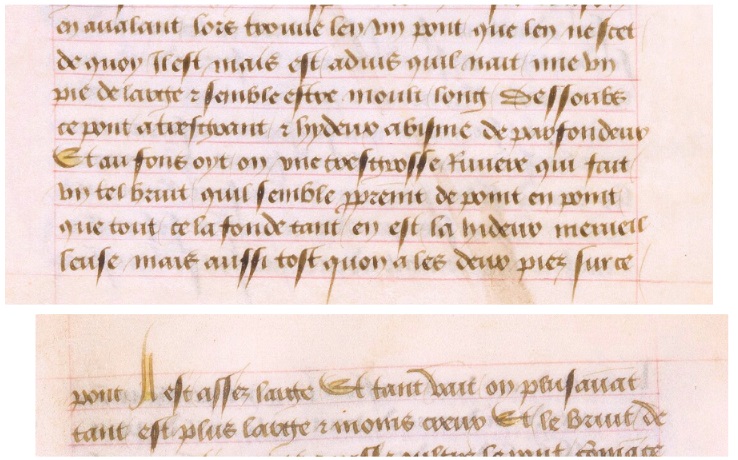

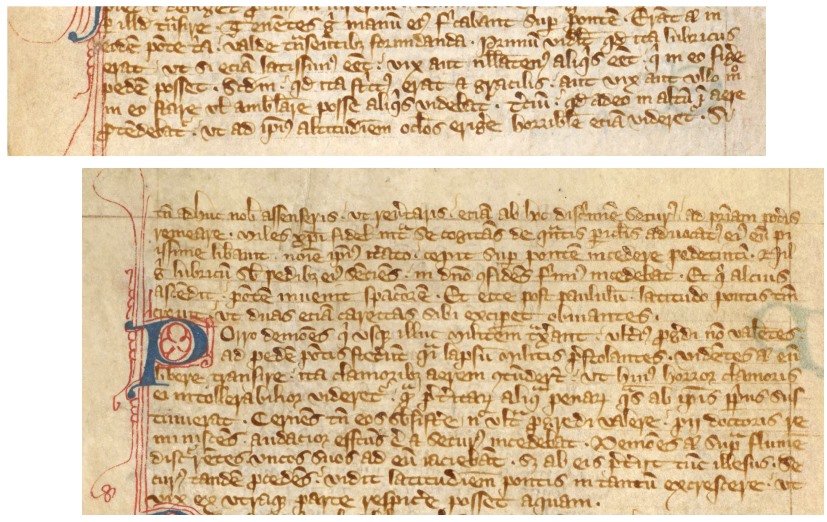

The author of “Guerrino the Wretch” proves to be well acquainted with the Irish legend, as his knight hero undergoes the same introductory procedure to the Purgatory as we already know from the writings of Henry of Saltrey. On his arrival in Ireland, he asks for the special permission to be issued by the local bishop. The bishop makes his usual attempts at changing the pilgrim's mind by addressing him with the customary warnings (Fig. 13):

«You are about to expose yourself to serious danger, for many who went in never came back».

[In the original Italian text: «Tu te meti a tanto periculo, ipero che molti vi sono andati che non sono tornati»].

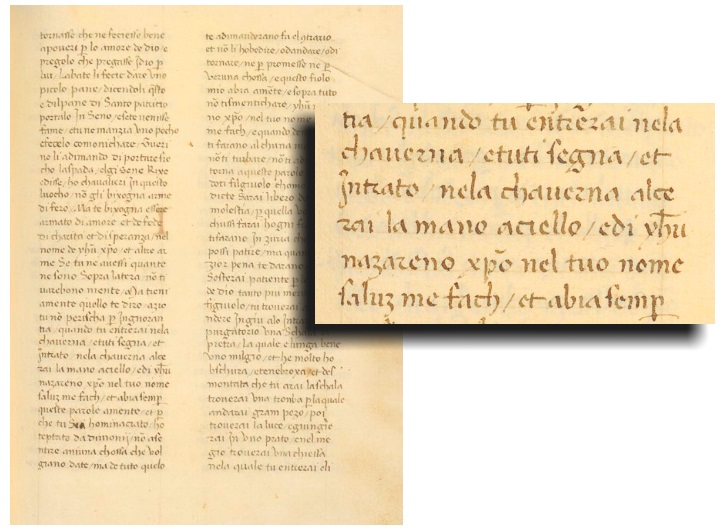

Then the bishop sends him to the island where the Purgatory lies, with a presentation letter to be delivered to the prior of the adjacent church. Guerrino goes through the usual nine days of fast, prayer and penitence. Before the entrance to the Purgatory, a huge cavern which proceeded under the ground, («una grandissima caverna che andava sotto terra»), he is given by the prior the same advice as he was told by the hermits before entering the Sibyl's Cave, with the recommendation to utter the same invocation as pronounced by Henry of Saltrey's knight, Owein, in his “Tractatus de Purgatorio Sancti Patricii” (Fig. 14):

«When you will enter the cave, cross yourself, and after your entrance raise your hand to the heaven while saying 'Jesus Christ of Nazareth, in your name make me safe».

[In the original Italian text: «Quando tu entrerai nela chaverna, e tu ti segna, et intrato nela chaverna alzerai la mano a ciello e di' Iesu Nazareno Christo nel tuo nome salvum me fach'»].

And Guerrino the Wretch is locked into St. Patrick's Purgatory. The same way as knight Owein was.

In the Purgatory, Guerrino undergoes the same demonic trials as described by Henry of Saltrey, with a concurrent, patent effort to revisit narrative schemes contained in Dante Alighieri's “Divine Comedy”. After the encounter with the usual men dressed in white robes, Guerrino is seized by the demons and brought to the punishments we already known, including the well-known, huge wheel provided with pointed hooks («grandissima rota con denti de ferro aguzi»).

As we already noticed in our previous article “Antoine de La Sale and the magical bridge concealed beneath Mount Sibyl”, Guerrino also meets the well-known 'test bridge', which - it is to be reminded - Antoine de la Sale liked to place in the Sibyl's Cave (Fig. 15):

«... and immediately he was standing on a bridge that crossed the marsh from one side to the other over a large river. And it seemed to him that the bridge was so narrow that nobody could have put one foot ahead of the other. He turned to get back but he could not see the bridge beneath his own eyes. And he saw countless jaws of big snakes and dragons, and it was as if they were waiting for him to fall down. Guerrino had never been so scared as in this predicament. And all the way along the bridge he feared he would fall. And actually he was about to fall: but he called on the Holy Name, and by His mercy the bridge swell to a huge width. And he could go through this perilous passage».

[In the original Italian text: «... e subito fu drito sopra uno ponte che trapassava questo lagune da uno lato al altro sopra uno grande fiume. E parevali questo ponte tanto sottile, che uno piede avanti l'altro non li poteva stare. Lui se volse per tornare e non vide el ponte abasso gli ochi. E vide infinite bocche de grandi serpenti, e dragoni, e pareva che aspetassero che lui cadesse. Anchora non havea avuto Guerino magior paura che questa. E tutta via li parea de cadere. E pure saria caduto: ma chiamò el santo nome, e per la soa misericordia el ponte se li fece largissimo. E passò de là da questo fortunoso passo»].

The whole narrative is so expanded and redundant that Guerrino even stumbles upon a second 'test bridge':

«And he saw a river that was crossed by so thin and narrow a bridge that there was no small animal that would pass through it, because of his tiny width. He crossed himself and entrusted himself to God. He was taken [by the demons] and placed onto the middle of the bridge, where they left him, then they began to scream at him, and flung stones and shafts at him so that he was about to fall. And he turned to go back , and could see no bridge. So he looked at the bottom where the water was, and saw that it was full of hideous worms and snakes. The bridge was so thin that it was not possible to put one foot ahead of the other. He began to call the name of Jesus Christ from Nazareth, and the bridge started to get larger. As he spoke these words thrice, he began to sing 'Domine ne in furore tuo arguas me', and the bridge became even larger, and he was through».

[In the original Italian text: «e vide uno fiume cui atraverso li era uno ponte tanto sutile e streto che lo non è si picolo animale che havesse potuto passare, tanto era streto. Lui se fece el segno de la santa croce e recomandose a dio. Fu preso [dai demoni] e posto suxo el mezo del ponte et ivi lo lassorono, e poi cominciarono a cridare et a zitarli pietre e pali per modo che el meschino fu per cadere. E lui se volse indietro per tornare indietro, e non vide ponte. Alhora pose mente nel fundo de laqua, e lo vide pieno de vermini bruti e serpenti. El ponte era si stretto che uno pié inanti l'altro non li cadeva. Lui cominciò a chiamare iesu christo nazareno, e lo ponte si cominciò a largare. E dite queste parole tre volte, cominciò a cantare 'Domine ne in furore tuo arguas me', et el ponte se largava, e lui passò»].

Following this verbose description of purgatorial punishments, Guerrino attains the Paradise and is finally brought back by angels to the initial chamber of the Purgatory. The door is unlocked and the prior celebrates his safe return to the world of the living, the way is described in Henry of Saltrey “Tractatus de Purgatorio Sancti Patricii”.

Before crossing the door, Guerrino asks the accompanying angels his fateful question about his own lineage, still unknown to him. And he gets the answer he has been earnestly looking for throughout the entire romance (Fig. 16):

«I beseech you, that you tell me who my father is [...] You are of kingly descent»

[In the original Italian text: «Io vi priego che vui me insignati chie mio padre [...] Tu sei di schiata Reale»].

Thus, in Andrea da Barberino's romance, Guerrino the Wretch travels into a subterranean Otherworld of demons and purgatorial punishments, as a sequel to a previous journey made into another subterranean realm, that of the Sibyl, similarly inhabited by demonic presences. And the narrative connection between the two episodes is confirmed by the fact that here, at St. Patrick's Purgatory, Guerrino is finally given the answer that was repeatedly denied to him in the preceding otherwordly travel, when the Sibyl had refused to unveil his lineage to him (Fig. 17):

«O much wise Sibyl I beseech you by your power, that you consent to tell me who my ancestry was, and who my father and mother were [...] From me you won't get any other information apart from what you know already».

[In the original Italian text: «O sapientissima Sibilla io te prego per la tua virtu chel te sia de piazere de dirme chui sono li mei antichi et cui e el mio padre e la mia madre [...] Da mi non saperesti nessuna cossa piui inanzi de quelo che tu sa»].

The Sibillini Mountain Range and its legends. The mythical tale of St. Patrick's Purgatory. Both feature a lake and a cave. Both are inhabited by demons and marked by otherwordly characters. It is not a surprise that we find a transfer of narrative topics and situations from the illustrious and widely-known Irish tale, to an Italian tale with some narrative traits in common, despite the total independence of the two legendary settings.

There is no direct connection between the two legends. However, a contamination of narrative themes was certainly fostered by the mutual similarities which plainly marked the two sites: two lakes, two eerie caverns, both providing an access to an Otherworld, a purgatorial afterlife in Ireland and a subterranean, demonic realm in the Italian Apennines. A contamination that travelled across the centuries of the Middle Ages, through an invisible streams of oral tales and storytelling, which finally materialised within the fifteenth-century works written by Antoine de la Sale and Andrea da Barberino.

And another significant common trait exists.

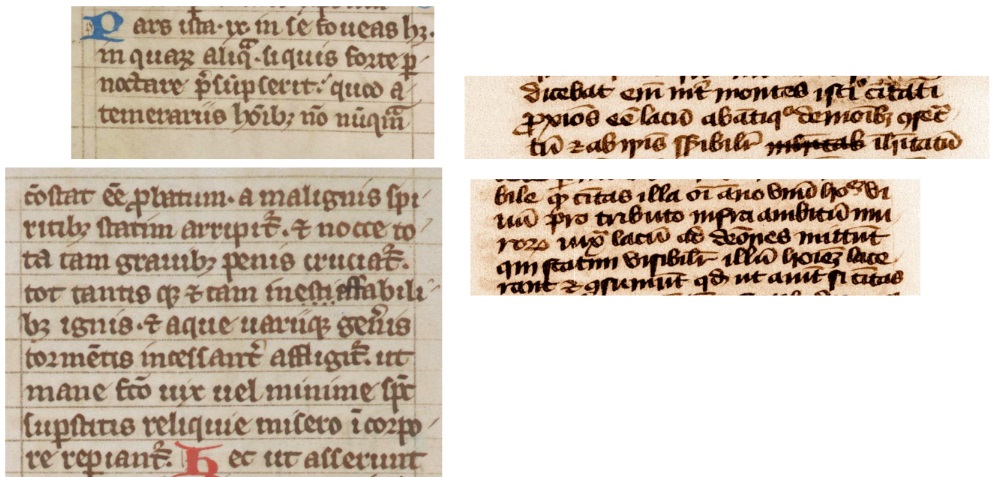

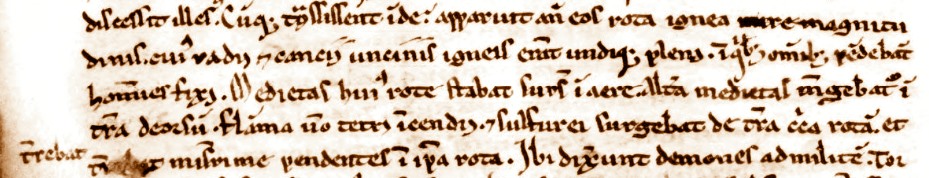

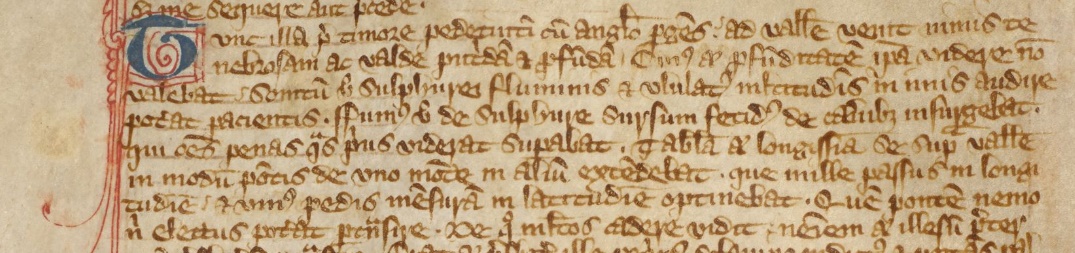

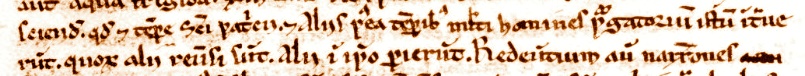

To highlight it, we must go back to the ghastly words written by Gerald of Wales (Giraldus Cambrensis) in his “Topographia Hibernica” (“Topography of Ireland”), dating to the year 1188.

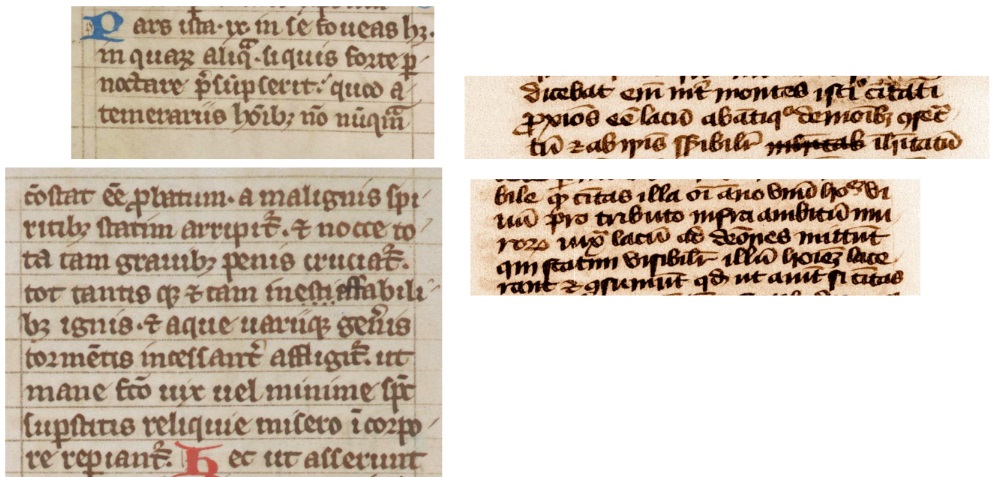

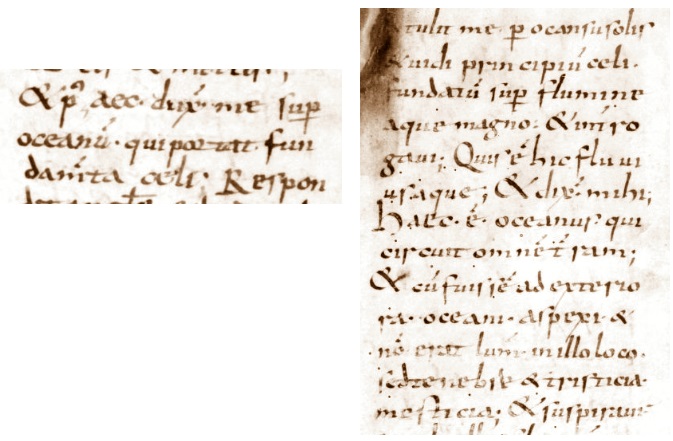

In describing the Purgatory of St. Patrick, Gerald writes the following sentence (Fig. 18 - left):

«There is a lake in Ulster containing an island divided into two parts. [...] The other part, being covered with rugged crags, is reported to be the resort of devils only, and to be almost always the theatre on whichcrowds of evil spirits who visibly perform their rites [...] This part of the island contains nine pits, and should anyone perchance venture to spend the night in one of them [...], he is immediately seized by the malignant spirits, who so severely torture him during the whole night, inflicting on him such unutterable sufferings by fire and water, and other torments of various kinds, that when morning comes scarcely any spark of life is found left in his wretched body».

[In the original Latin text: «Est lacus in partibus Ultoniae continens insulam bipartitam. [...] Pars altera, hispida nimis et horribilis, solis daemoniis dicitur assignata; quae et visibilibus cacodaemonum turbis et pompis fere semper manet exposita [...] Pars ista novem in se foveas habet. In quarum aliqua si quis forte pernoctare praesumpserit, [...] a malignis spiritibus statim arripitur, et

nocte tota tam gravibus poenis cruciatur, tot tantisque et tam ineffabilis ignis et aquae variique generis tormentis incessanter affligitur, ut mane facto vix vel minimae spiritus superstitis reliquiae misero in corpore reperiantur»].

But the above words strongly bring to our mind another Lake, and the description provided of it by Petrus Berchorius in the fourteenth century (Fig. 18 - right):

«Amid the peaks which raise near that town [Norcia] there is a lake, which from antique times is sacred to demons and conspicuously inhabited by them [...] each year that town sends a single man, a living man, beyond the walls that encircle the lake, as an offering to the demons, who immediately and in full view tear apart and slaughter that man».

[In the original Latin text: «Inter montes isti civitati proximos esse lacum ab antiquis daemonibus consecratum et ab ipsis sensibiliter inhabitatum [...] quia civitas illa omni anno unum hominem vivum pro tributo infra ambitum murorum iuxta lacum ad daemones mittunt, qui statim visibiliter illum hominem lacerant et consumunt»].

An Irish lake with its pits, Lough Derg, and an Italian Lake seem to share a same terrific character: both are inhabited by a same sort of demons; they are visibly and manifestly inhabited by them; people who cross their boundaries are immediately seized; their bodies are tortured and slaughtered.

It is clear that a narrative contamination has been taking place amid the two mutually distant lakes.

And we believe that the keyword to the legendary tale of the Sibillini Mountain Range is, again, Otherworld. An Otherworld that was believed could be accessed by men through a Cave and a Lake. In full analogy with the passageways that were reputed to exist at St. Patrick's Purgatory, Ireland, and Cumae, Italy.

The three tales were very similar. And, in a legendary framework, the Sibillini Mountain Range was fully fit to house a third, fateful, appalling entrance to the Otherworld.

Monti Sibillini, un Lago e una Grotta come accesso oltremondano /4.4 Ulteriori affinità mitiche: Lough Derg e i Monti Sibillini

Nei precedenti paragrafi abbiamo illustrato la mitica narrazione relativa a Cuma, nella quale sono rappresentati un lago, il Lago d'Averno, e una grotta situata nelle immediate vicinanze; quest'ultima era ritenuta costituire, in antico, l'ingresso a un Aldilà. Abbiamo anche evidenziato i collegamenti narrativi che connettevano il racconto cumano, diffusamente conosciuto in tutta Europa a motivo della sua presenza nell'"Eneide" virgiliana, con le leggende che abitavano i Monti Sibillini, caratterizzati anch'essi da un proprio Lago e una propria Grotta.

Ma le affinità non terminano qui. Abbiamo anche visto come una terra dell'Europa settentrionale, l'Irlanda, ospitasse un altro racconto leggendario: ancora, un lago, Lough Derg, e ancora una grotta, che si reputava potesse fornire l'accesso a un altro Aldilà, il Purgatorio di San Patrizio. E anche questo racconto era conosciuto in tutta Europa, nella penisola italiana e, in modo specifico, come vedremo più avanti in questo medesimo articolo, nella stessa Italia centrale.

Un esempio estremamente significativo della straordinaria notorietà del Purgatorio di San Patrizio è costituito dalla "Legenda Aurea", la raccolta di racconti concernenti la vita e la morte di più di centocinquanta santi elaborata da Jacopo da Varagine, un frate domenicano che fu vescovo della città di Genova, nella seconda metà del tredicesimo secolo.

La "Legenda Aurea" fu un'opera di grande successo, una sorta di 'best seller' che ha attraversato molti secoli, con migliaia di manoscritti ancora sussistenti. La "Legenda" era considerata come una fonte estremamente utile al fine di individuare temi ed esempi da impiegare nelle attività di predicazione, ed era apprezzata da lettori e ascoltatori appartenenti a ogni estrazione sociale, a motivo delle affascinanti narrazioni in essa contenute che raccontavano impressionanti, commoventi episodi di martirio subìto da santi cristiani, uomini e donne, e grazie anche alla grande leggibilità del testo, redatto in un latino semplice ma comunque fluente.

E, certamente, la "Legenda Aurea", nel Capitolo XLIX, posto subito dopo la sezione dedicata a un veneratissimo santo, Benedetto da Norcia, non dimenticava affatto di menzionare il Purgatorio di San Patrizio (Fig. 1 e 2):

«Il Signore comandò dunque che egli [San Patrizio] tracciasse in un certo luogo un grande cerchio nel suolo, utilizzando il suo bastone, ed ecco che la terra all'interno del cerchio si aprì e apparve un abisso enorme e profondissimo; e a San Patrizio fu rivelato che lì si apriva l'ingresso del Purgatorio; chiunque fosse disceso in esso, non avrebbe sofferto ulteriori punizioni, né avrebbe fatto esperienza del purgatorio a causa dei propri peccati. Molti, però, non sarebbero mai tornati da esso, e coloro che fossero riusciti a ritornare non avrebbero dovuto rimanere in esso se non da un mattino fino al mattino seguente. E molti, dunque, entrarono, e non ne tornarono mai più».

[Nel testo originale latino: «Jussu igitur domini in quodam loco magnum circulum cum baculo designavit et ecce terra inter circulum se aperuit et puteus maximus et profondissimus ibi apparuit revelatumque est beato Patricio, quod ibi purgatorii locus esset, in quem quisquis vellet descendere, alia sibi poenitentia non restaret nec aliud pro peccatis sentiret purgatorium, plerique autem indem non redirent et qui redirent eos a mane usque in sequens mane ibidem moram facere oporteret. Multi igitur ingrediebantur, qui de caetero non revertebantur»].

Questa è la descrizione della leggenda del Purrgatorio di San Patrizio così come essa viene riferita nel capitolo dedicato al santo irlandese contenuto nella "Legenda Aurea", un passaggio che è manifestamente tratto dal "Tractatus de Purgatorio Sancti Patricii" scritto da Henry de Saltrey.

Jacopo da Varagine, inoltre, non tralasciò di includere, nella propria opera, l'intero racconto dell'agghiacciante discesa di Owein nel Purgatorio di San Patrizio; e dunque la sua narrazione prosegue ancora, con una modifica apportata al nome del protagonista principale (Fig. 3):

«Un certo nobiluomo di nome Nicholaus, che molto aveva peccato [...] volle entrare nel Purgatorio di San Patrizio; e così, per i quindici giorni precedenti egli si consumò nel digiuno, così come tutti erano soliti fare; in seguito, la porta fu aperta utilizzando la chiave che era custodita presso l'abbazia, ed egli discese nella cavità...»

[Nel testo originale latino: «Quidam vir nobilis nomine Nicholaus, qui peccata multa commiserat [...] purgatorium sancti Patricii sustinere vellet, cum antea quindecim diebus, ut omnes faciebant, se ieiuniis macerasset, aperto ostio cum clavi, quae in quadam abbatia servabatur, in praedictum puteum descendit...»].

Segue poi un lungo resoconto del viaggio di Nicholaus attraverso il Purgatorio, parimenti tratto dall'opera di Henry di Saltrey. Egli incontra gli stessi uomini vestiti di bianco, che gli consigliano di invocare il nome di Gesù nel momento in cui si troverà costretto a subire le terribili torture del Purgatorio («cum te poenis affligi senseris, protinus clama et dic: 'Jesu Christe fili Dei vivi miserere mihi peccatori»), un'implorazione alla quale anche Guerrino il Meschino ricorrerà spesso nel romanzo di Andrea da Barberino (Fig. 4).

Poi, i demoni iniziano a mostragli le spaventose punizioni inflitte all'interno del Purgatorio. Le note visioni di fiamme e uncini e demoniache fruste, che già conosciamo per averle lette in Henry di Saltrey, tra le quali anche la celeberrima ruota di fuoco («rota maxima erat uncinis ferreis ignitis plena...») sono descritte anche da Jacopo. E la "Legenda Aurea" non omette di menzionare la presenza dell'ormai usuale meccanismo oltremondano costituito dal 'ponte del cimento', che, come sappiamo, ritroveremo anche nella Grotta della Sibilla (Fig. 5):

«Fu poi condotto in un luogo in cui poté vedere un ponte [...] il quale era strettissimo e lucido e scivoloso come il ghiaccio, al di sotto del quale scorreva un grande fiume di fuoco sulfureo, così da far sembrare che fosse impossibile attraversarlo [...] Egli, con fede, entrò nel ponte ponendo un piede su di esso, iniziando a pronunciare le parole 'Gesù Cristo ecc.' [...] A ogni passo egli ripeteva le medesime parole, e così passò senza danno».

[Nel testo originale latino: «Ductus igitur ad alium locum vidit quendam pontem [...] qui quidem erat strictissimus et instar glaciei politus et lubricus, sub quo fluvius ingens sulphureus et igneus fluebat, super quem dum se posse transire omnino desperaret [...] confidenter accessit et unum pedem super pontem ponens, Jesu Christe etc. dicere coepit [...] ad quemlibet passum eadem verba protulit et sic securus transivit»].

La straordinaria leggenda del Purgatorio di San Patrizio era integralmente conosciuta in Italia, con la sua grotta descritta da Henry di Saltrey e il suo lago, menzionato da Giraldus Cambrensis, e infine tramite la completa illustrazione di essa elaborata da Jacopo da Varagine. E possiamo facilmente dimostrare come, nel quattordicesimo secolo, la leggenda fosse pienamente nota anche nell'Italia centrale, in un luogo che distava non più di 70 chilometri dai Monti Sibillini. Nel 1346, Jacopo di Mino del Pellicciaio, un pittore originario di Siena, dipinse un affascinante affresco sulla parete del refettorio del convento di San Francesco al Borgo Nuovo, a Todi, in Umbria. L'affresco rappresenta proprio "Il Purgatorio di San Patrizio": si tratta di una significativa testimonianza del successo di quel racconto leggendario irlandese in un contesto culturale centroitaliano (Fig. 6).

Un lago e una grotta in Irlanda, che rendevano possibile un leggendario ingresso verso un Aldilà. Un altro Lago e un'altra Grotta, inoltre, nell'Italia centrale, a proposito dei quali venivano narrate storie di negromanzia e demoni.

In un precedente paragrafo, abbiamo già avuto occasione di notare come, nel medioevo, chiunque avesse preservato una seppur minima memoria dell'antichità classica avrebbe associato quel sito posto tra gli Appenini con Cuma, il suo lago, la sua grotta e la sua antica Sibilla.

Ma anche un'altra associazione risultava possibile.

Tutti, infatti, erano anche a conoscenza della leggenda medievale relativa al Purgatorio di San Patrizio, con il suo lago e la sua terrificante grotta. Un racconto leggendario che era riferito anche dalla notissima e largamente letta "Legenda Aurea". Dunque, ogni sinistro racconto concernente un ulteriore Lago e un'altra Grotta, situati tra gli Appennini e segnati da caratteri magici o oltremondani, avrebbe immediatamente riportato alla memoria, nella mente dell'ascoltatore, quel lontano e inquietante Purgatorio.

I narratori orali e, in tempi successivi, gli uomini di lettere non avrebbero potuto evitare di introdurre alcune combinazioni tra le due narrazioni, sostanzialmente estranee l'una all'altra: un lago e una grotta posti nell'Irlanda settentrionale, e un Lago e una Grotta giacenti in un massiccio montuoso che è parte della catena appenninica. Esattamente lo stesso processo di contaminazione, del tutto naturale a mano a mano che un racconto si espande e raggiunge platee differenti nel corso dei secoli, che produsse una combinazione tra il racconto sibillino dimorante tra gli Appennini e la leggenda che viveva a Cuma sin dall'antichità classica.

E dunque, ancora una volta, troviamo che punti di riferimento geografico posti tra gli Appennini sono in grado di generare un peculiare richiamo nei confronti di un diverso racconto leggendario, in questo caso proveniente dall'Iranda: e il risultato consiste nell'incorporazione di temi e suggestioni, connessi al Purgatorio di San Patrizio, all'interno della tradizione leggendaria dei Monti Sibillini, malgrado essi siano localizzati in un territorio del tutto differente.

Ancora una volta, il mitico racconto concernente un accesso oltremondano accessibile dagli uomini, situato in Irlanda, esperimentò una parziale migrazione verso l'area dei Monti Sibillini, con la progressiva aggiunta, da parte dei narratori orali, di dettagli ed emozioni ai propri racconti relativi a un gelido Lago e a una Grotta posta su di un picco montano, entrambi perduti in una remota regione degli Appennini italiani. Se un passaggio verso la vita oltre la vita esisteva in Irlanda, questa circostanza, per quanto mitica, non poteva che rafforzare e confermare ulteriormente il racconto italiano, a motivo di una palese analogia sussistente tra i due luoghi, entrambi segnati dalla presenza di un lago e di una grotta.