6 Jul 2017

The mysterious fame of the Sibillini Range: a map by Antoine de La Sale

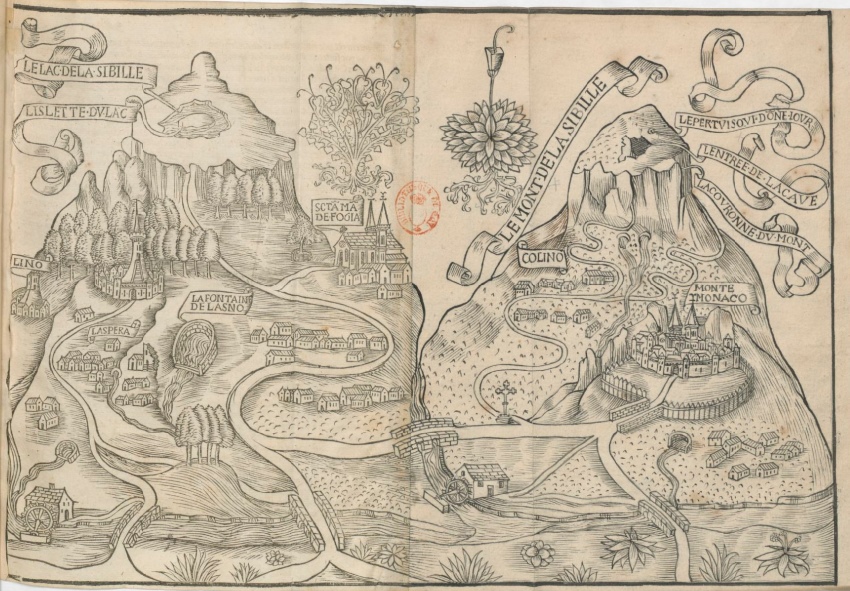

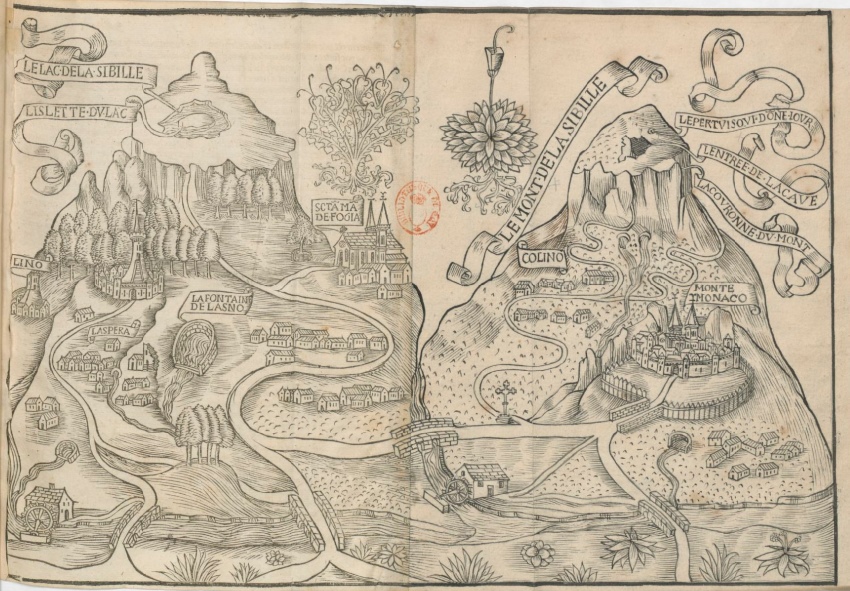

The drawing is quite remarkable: the Sibillini Range is portrayed with all its fascinating elements, the same who attracted travellers from centuries from all across Europe.

On the left side of the picture, a large mountain stands with a lake on its top: it's the “The Lake of the Sibyl” (“Le Lac de la Sibille” in the French caption), also known today as the Lake of Pilatus. On the right side is Mount Sibyl (“Le mont de la Sibille”), with its lofty crown (“la couronne du mont”) and featuring a gloomy hole on the very peak: it is the Sibyl's cave, or “the entrance to the cavern” (“l'entrée de la cave”). In the middle, the valley where the small hamlet of Foce (“Fogia”) guards the trail to the lake.

This is the map drawn by Antoine de La Sale, the French getleman who visited Mount Sibyl on May 18th 1420 and reported his journey in a famous work, “Le Paradis de la Reine Sibylle”. This version of the map is contained in a printed edition of his book, published in Paris in 1527.

“The Apennine Sibyl - A Mystery and a Legend” is proud to publish, for the first time ever, a high-resolution, high-quality version of de La Sale's drawing, with a full rendering of the tiniest details and all shades of 'chiaroscuro'.

The map is another remarkable instance of the widespread renown which the Sibillini Range enjoyed in past centuries among foreign countries all over Europe. The sinister lake with its demons, the dark cave which was the abode of a Sibyl were set in a unique, extraordinary mix of picturesque, hair-raising landscape and thrilling traditional lore: a combination that would push scores of noblemen, knights, adventurers and treasure hunters as far as this remote region of mountains and precipices.

You can download a high-quality, high-resolution version of Antoine de La Sale's map from here.

La misteriosa fama dei Monti Sibillini: una mappa di Antoine de La Sale

Il disegno è di grandissimo interesse: i Monti Sibillini sono ritratti con tutti i loro elementi più affascinanti, gli stessi che hanno attirato viaggiatori da tutta Europa per secoli.

Sul lato sinistro dell'immagine, si erge una grande montagna con un lago sulla cima: è "Il Lago della Sibilla" ("Le Lac de la Sibille" nella didascalia francese), noto oggi come il Lago di Pilato. Sulla destra, il Monte Sibilla (“Le mont de la Sibille”), con la sua imponente corona (“la couronne du mont”) e, proprio sulla vetta, un'oscura apertura: è la grotta della Sibilla, o "l'ingresso della caverna" (“l'entrée de la cave”). Al centro, la vallata dove il piccolo villaggio di Foce ("Fogia") custodisce il sentiero che conduce al lago.

È questa la mappa disegnata da Antoine de La Sale, il gentiluomo francese che si recò al Monte Sibilla il 18 maggio 1420, raccontando la propria escursione nell'opera "Le Paradis de la Reine Sibylle". Questa versione della mappa è contenuta nell'edizione a stampa del "Paradis", pubblicata a Parigi nel 1527.

"Sibilla Appenninica - Il Mistero e la Leggenda" è lieta di pubblicare, per la prima volta, una versione ad alta risoluzione e di elevata qualità del disegno di Antoine de La Sale, con una perfetta resa di ogni dettaglio e di tutte le sfumature del chiaroscuro.

La mappa costituisce un ulteriore significativo esempio della grandissima fama della quale hanno goduto i Monti Sibillini nei secoli passati in tutti i Paesi d'Europa. Il lago sinistro con i suoi demoni, la grotta oscura ritenuta il regno di una Sibilla erano incastonati in un unico, irripetibile scenario costituito da un panorama pittoresco e sublime e da tradizioni ricche di affascinante emozione: una combinazione che avrebbe spinto schiere di nobili, cavalieri, avventurieri e cacciatori di tesori fino a questa remota contrada di montagne e precipizi.

È possibile visualizzare una versione di elevatissima qualità della mappa di Antoine de La Sale qui.

6 Jul 2017

“A-Hundred-Leaves”: a green encounter in the Paradise of Queen Sibyl

Walking around the highlands of the Sibillini Range, one cannot forget the words written by Antoine de La Sale in his “The Paradise of Queen Sibyl”, depicting a journey to the Sibyl's cave which occurred in year 1420: «from mid-height upwards, there are the most pleasant and charming grasslands, which hardly can be imagined, as they are so adorned with herbage and flowers of manyfold colors and remarkable fashions, that they send out the most agreeable scent».

Today, the contemporary trekker is totally immersed in the same landscape portrayed by de La Sale six hundred years ago. And the utmost delight may pervade your soul when an unexpected encounter occurs: a plant that seems to have materialized direct out of one of the fine miniature paintings contained in the French gentleman's original manuscript, now at the Library of the Condé Museum in Chantilly.

Here is how Antoine de La Sale describes what he calls the “A-Hundred-Leaves” plant: «another herbage to be found there, which I never saw elsewhere, is called 'ly cento follie', that is the 'A-Hundred-Leaves', and truly it's a fitting name because it has exactly one hundred leaves».

As you can see in the two pictures (the second taken near Poggio di Croce, a peak overlooking Castelluccio di Norcia), the correspondence appears to be striking (apart from the flower, possibly popping up in springtime). And you if you try to count up the number of leaves, you will find that de La Sale was nearly right!

This is the unparalleled magic of the Sibillini Range: an ancient manuscript talks to you, and the past suddenly becomes today, so that you can touch it with your hand.

[Antoine de La Sale's words in the original French version: «de la moytié en sus, sont tous prez les plus beaulx et plaisans, que à peine pourroit-on deviser, car tant y sont herbes et fleurs de toutes couleurs et estranges manieres, qui sont si trés odorantes que c'est ung très grand plaisir. [...] Une autre herbe y a, que oncques je n veis [que] là, que ilx appellent 'ly cento follie', c'est-à-dire le cent feuilles, et vrayement elle n'est point surnommee, car elle a cent fueilles, ne plus ne moins.»]

“Centofoglie”: un incontro verde nel Paradiso della Regina Sibilla

Camminando attraverso le praterie d'alta quota dei Monti Sibillini, non si possono dimenticare le parole scritte da Antoine de La Sale nel suo "Paradiso della Regina Sibilla", l'opera che descrive la sua escursione alla grotta della Sibilla, effettuata nell'anno 1420: «da mezzacosta fino alle cime, vi sono prati bellissimi e piacevolissimi, i quali difficilmente si possono immaginare, perché sono così ricolmi di erbe e fiori di tutti i colori e delle più strane fogge tanto da essere profumatissimi, rappresentando così un immenso piacere».

Oggi, l'escursionista dei nostri tempi è completamente immerso nello stesso panorama descritto dal de La Sale seicento anni fa. E un vero piacere può invadere il vostro cuore quando ha luogo un incontro inaspettato: una pianta che pare essersi materializzata direttamente da una delle pregevoli miniature contenute nel manoscritto originale redatto dal gentiluomo provenzale, oggi custodito presso la Biblioteca del Museo di Condé a Chantilly.

Ecco come Antoine de La Sale descrive quella che egli chiama "pianta centofoglie": «un'altra specie vegetale che si trova qui, e che mai ho potuto vedere altrove, è chiamata dalla gente del luogo 'ly cento follie', vale a dire la cento foglie, e davvero il suo nome non appare immeritato, perché essa ha veramente cento foglie, né più né meno».

Come potete vedere nelle due immagini (la seconda scattata in località Poggio di Croce, un'elevazione che sovrasta Castelluccio di Norcia), la corrispondenza risulta essere veramente impressionante (a meno del fiore, che forse sboccia in primavera). E se provate a contare il numero di foglie, troverete che de La Sale non è stato di certo impreciso!

È questa la magia unica dei Monti Sibillini: un antico manoscritto ci parla, e il passato diviene improvvisamente l'oggi, tanto da poterlo toccare con le nostre mani.

[Ecco le parole di Antoine de La Sale nella versione originale francese: «de la moytié en sus, sont tous prez les plus beaulx et plaisans, que à peine pourroit-on deviser, car tant y sont herbes et fleurs de toutes couleurs et estranges manieres, qui sont si trés odorantes que c'est ung très grand plaisir. [...] Une autre herbe y a, que oncques je n veis [que] là, que ilx appellent 'ly cento follie', c'est-à-dire le cent feuilles, et vrayement elle n'est point surnommee, car elle a cent fueilles, ne plus ne moins.»]

25 Feb 2016

“Guerrino The Wretch” and the replaced Sibyl

“Guerrino the Wretch”: a fifteenth-century best seller. And yet, a book subject to revision and editing by the papal authorities: apparently, the Apennine Sibyl was attracting to many visitors to her seductive realm, and the Roman Church wanted to limit the circulation of this pagan hearsay among readers.

This is manifestly seen when we compare the fifteenth-century edition of “Guerrino” to the later 1689 edition. Let's read together a same passage:

>>> 1480 Edition (above in the picture)

«He [Guerrino] determined to inquire the SIBYL once more and to implore her in case she proved unwilling to tell. And when she had turned again to her original shape he went to her and so he spoke to her: “O perfectly wise SIBYL, I do appeal to your righteousness, please tell me who my ancestors were, and my Father and Mother, so my labour may not be lost”.

She replied: “I regret what I already told you: really you were born from an illustrious lineage, yet you are proving to be a knight so utterly impolite”.

After listening to her answer he felt troubled and angrily replied to her “[...] please tell me the name of my father”, but the SIBYL laughed at him and said: “Sir Aeneas of Troy was far more prominent than you, I led him through the netherworld and showed to him the likeness of his father Anchises...”»

And the following is the same excerpt as it appears in the 1689 Venetian edition, published at the time “by permission of the Supervisors” as indicated in the book's cover:

>>> 1689 Edition (below in the picture)

«And he [Guerrino] determined to inquire the FAIRY once more and to implore her in case she proved unwilling to tell. And when she had turned again to her original shape he went to her and so he spoke to her: “O perfectly wise FAIRY, I do appeal to your righteousness, please tell me who my ancestors were, that is my Father and Mother, so my labour may not be lost”.

She replied: “I regret what I already told you, that you were born from an illustrious lineage, yet you are proving to be a knight so utterly impolite”.

After listening to her answer he felt troubled and angrily replied to her “[...] please tell me the name of my Father and Mother”, but the FAIRY laughed at him and said: “Much more kind to me was Sir Aeneas of Troy, I led him through the Netherworld and showed to him the likeness of his father Anchises...”»

Throughout the 1689 book, the word “Sibyl” has been replaced by “Fairy” and “Alcina” (originally an evil fairy in Ludovico Ariosto's “Orlando Furioso”). In addition to that, a whole chapter (146 in the earlier edition) has been totally removed: in it, the Sibyl explained to Guerrino that she actually was the Cumaean Sibyl, and stated a full list of Sibyls.

In past centuries the Church had not always maintained such a negative attitude with respect to the Sibyls: early Christian authors had declared that the pagan prophetesses had foretold the coming of Christ on earth and therefore they were to be considered as part of God's mysterious design on the Salvation of men.

“Guerrin Meschino” e la Sibilla sostituita

“Guerrin Meschino”: un best seller del quindicesimo secolo, ma anche un libro sottoposto a tagli e revisioni da parte delle autorità pontificie: forse perché la Sibilla Appenninica richiamava troppi visitatori presso il proprio regno di seduzione, desiderando così la Chiesa di Roma che fosse posto un freno alla circolazione, tra i lettori, di quella leggenda pagana.

Ciò è palesemente visibile se andiamo a confrontare l'edizione quattrocentesca del “Guerrino” con la più tarda edizione del 1689. Leggiamone insieme un passaggio:

>>> Edizione 1480 (in alto nella figura)

«Deliberò pregare da capo la SIBILLA e se lei no lo voria dire p[er] pregare de sconzurarla. E como ella fo retornata in suo essere andò a lei e in questa forma li parlò. "O sapientissima SIBILLA io te prego per la tua virtù che te sia piacere de dirme cui fu[ro]no li miei antichi e cui è el mio padre e la mia madre, azo io no habia p[er]duto tanta faticha in darno".

Lei respose: "a mi me rencresce quelo che io te o dito: iperò che tu sei nato de gentil legnazo e sei tanto vilano cavaliero".

Quando intese la sua resposta tuto turbato con ira respose inverso da lei: "[...] prego che tu me insegni el padre mio". E la SIBILLA sene rise e disse: "el duca Eneas troiano so de più gentil nazione di te et lo condussi per tuto lo inferno, e mostroli lo suo padre Anchise..."»

E questo che segue è il medesimo brano, tratto però dall'edizione veneziana del 1689, pubblicata all'epoca “con Licenza de' Superiori”, così come indicato nella copertina del volume:

>>> Edizione 1689 (in basso nella figura)

«E deliberò di pregare da capo la FATA, e se lei non gli lo volesse dire di pregarla, e scongiurarla: e com'ella fu tornata nel suo esser, andò da lei, e in questa forma li parlò: "O sapientissima FATA, io ti prego per la tua virtù, che ti sia in piacere di dirmi chi son li miei Antichi, cioè mio Padre, e mia Madre acciocché io non habbi fatto tanta fatica in darno".

Lei rispose: "a me rincresce di quello, ch'io t'ho detto, ch'essendo nato di gentil lignaggio, e tu sei tanto villano Cavaliero".

Quando Guerino intese la risposta, restò del tutto turbato, e con ira li disse: "[...] ti prego, che tu m'insegni il Padre, e la Madre mia". E la FATA se ne fece beffe, e disse: "il Duca Enea Troiano fu più gentil di te, e lo condussi per tutto lo Inferno, e gli mostrai il suo Padre Anchise..."»

In tutto il volume edito nel 1689, la parola “Sibilla” è stata sostituita con “Fata” e anche “Alcina” (in origine una fata malvagia che appare nell'”Orlando Furioso” di Ludovico Ariosto). Inoltre, un intero capitolo (il 146 nell'edizione più antica) risulta essere stato completamente rimosso: in esso, la Sibilla spiegava a Guerrino che lei era in effetti la Sibilla Cumana, ed esplicitava una lista di Sibille.

Occorre ricordare come, nei secoli passati, la Chiesa non abbia sempre mantenuto un giudizio negativo sulle Sibille: infatti, i primi apologeti cristiani avevano dichiarato come le profetesse pagane avessero preannunciato l'avvento di Cristo sulla terra, e dunque esse dovevano essere considerate come parte del misterioso disegno divino sulla salvezza degli uomini.

15 Feb 2016

The vertiginous peaks of the Sibillini Range

The Sibillini Mountain Range - The original fifteenth-century version of the romance “Guerrino the Wretch” by Andrea da Barberino fully convey their savage charm:

«Following the departure of Guerrino from the three hermits, it was not a long time before he reached the top of the two mountains, which surmounted the hermits' dwelling. He treaded a mountainous ridge that was made of bare rock; and flanking this crest of the two mountains there were sheer ravines so precipitous that the bottom of the vertiginous gorges could not be perceived, and the peaks above seemed to attain the elevation of clouds»

[In the original italian version: «Artito el Meschino dali tre remiti poco andò che trovò el fine de le due montagne che quello remitorio era per lo mezo tra queste doe alpe a pé; se move el colle de una montagna tuta de uno saxo vivo; e questo fine de queste doe montagne sono si grande et si profundi derupamenti chel non se pote vedere el fundo del grande valone e le ripe dove quelli feniscono li parve come azozeno fino de sopra a le nivole»]

Le cime vertiginose dei Monti Sibillini

Il massiccio dei Monti Sibillini – La versione originale quattrocentesca del romanzo “Guerrin Meschino” di Andrea da Barberino ne rappresenta fedelmente il carattere selvaggio:

«Dopo che il Meschino ebbe lasciato i tre eremiti, non passò molto tempo che egli si trovò sulla cima delle due montagne che incombevano su quel romitorio, posto ai piedi di esse; percorse la cresta di una montagna tutta fatta di roccia viva; e sulla cima di queste due montagne erano dirupi così grandi e profondi che non si poteva vedere il fondo dell'immenso vallone, e le vette dove quelli finivano gli sembrarono elevarsi fin oltre le nuvole».

17 Jan 2016

Guerrino enters the Sibyl's cave

GUERRINO THE WRETCH, edition1480:

«Flint, steel and tinder were now needed by the Wretch who had entered the gloomy cavern; and through the large clefts amid the rocks he found ghastly cavities: and they were tortuous indeed, and for three times he arrived to huge cracks which led outside on the mountain-side so he had to recoil, the torchlight failing to him...»

(Fifteenth-century Italian text: «Azalino et esca adesso faceua bisogno al Meschino che era intrato ne la scura caverna: e per le grande fenditure de li saxi trovò molte paurose cauerne: et andaua molto volzando e per tre volte ariuò a grande boche che insinuano fora de le montagne e conveniua tornare in drieto, el dopiero li veniua a mancho...»)

Guerrino entra nella caverna della Sibilla

GUERRINO IL MESCHINO, edizione 1480

«Azalino et esca adesso faceua bisogno al Meschino che era intrato ne la scura caverna: e per le grande fenditure de li saxi trovò molte paurose cauerne: et andaua molto volzando e per tre volte ariuò a grande boche che insinuano fora de le montagne e conveniua tornare in drieto, el dopiero li veniua a mancho...»

(«Esca ed acciarino ora si rendevano necessari al Meschino, che era entrato nell'oscura caverna: e attraverso le grandi fenditure tra le rocce trovò molte paurose cavene: ed era molto tortuosa e per tre volte arrivò a grandi aperture che conducevano fuori dalla montagna e conveniva dunque tornare indietro, la torcia venendogli a mancare...»)

6 Dec 2016

Guerrino and the Sibyl

«The Sibyl was concealing her rosy face behind a veil, her eyes sparkling with ardent love. From time to time her eyes met with Guerrino's, and the love he saw in their shine inflamed him and because of it his heart was so entirely flooded with fire as to become oblivious of all other things around him. […]

In the night he was ushered into a princely room, where the Sibyl, who wished to enchant him with her loving arts, came to entertain him with all pleasures and playful caresses that fit a man's body. When he lay down on the bed, she at once went next to him showing her gorgeousness and tender flesh: her breasts looked like polished ivory»

Andrea da Barberino, “Guerrino The Wretch”, chivalric romance, 1410 - The first account of the presence of a Sibyl in the Sibillini Range in Italy.

Guerrino e la Sibilla

«La Sibilla sotto un sottil velo teneva coperta la vermiglia faccia con due occhi accesi di ardente amore. Spesso i suoi occhi si scontravano con quelli di Guerrino, il suo amore lo accese e per quello ardeva così tanto da dimenticarsi ogni cosa.

[...]

Intanto, alla sera, egli fu menato in una ricca stanza, dove la Sibilla, per farlo innamorare, venne con tutti quei piaceri e giochi che fossero possibili ad un corpo umano. Quando fu adagiato nel letto si avventò al suo lato mostrando la sua bellezza e le sue bianche carni: le mammelle sembravano d’avorio.»

Andrea da Barberino, “Guerrin Meschino”, romanzo cavalleresco, 1410 – La prima testimonianza della presenza di una Sibilla nel massiccio dei Monti Sibillini.

12 Aug 2016

Guerrino the Wretch: the romance

"Guerrino the Wretch", the fifteenth-century romance by Andrea da Barberino: Norcia, the Apennine Sibyl, the Sibillini Mountain Range.

Guerrin Meschino: il romanzo

“Guerrin Meschino”, il romanzo cavalleresco del XV secolo scritto da Andrea da Barberino: Norcia, la Sibilla Appenninica, il massiccio dei Monti Sibillini.

12 Aug 2016

Guerrino and the rumours about the Sibyl's cave

«And an elderly man, who had listened to their words, replied to him: "Sir, he said the truth and I confirm to you that a Sibyl actually dwells beneath our mountain fastnesses" [...] One Frenchman Sir Lionel of Saluzzi boastfully said he had pushed himself up there, for a great love of his for a maiden, yet he had dared not enter the cave due to the wind which fiercely roared from the cavern's mouth, and an overwhelming obstruction of rocks, rubble, ravines, crags, gullies and deep gorges which hindered the passage of the boldest wayfarer"»

Guerrino e le dicerìe a proposito della grotta della Sibilla

«E un vecchio, che aveva pur esso prestata attenzione a quei discorsi, replicò: "O gentiluomo egli ha detto il vero ed io posso assicurarvi che questa Sibilla sta in queste nostre montagne [...] Un certo messer Lionello di Saluzzi di Francia, il quale, pel grande amore che portava ad una damigella, si era vantato di essere andato lassù, ma di non essere entrato all’interno per i grandi venti che spiravano dalla bocca dell’entrata, oltre che pei grandi ostacoli di pietre, rovine, burroni, sbalzi, precipizi e vallate che qua e là intercettavano ai passanti il cammino"»

31 Lug 2016

A medieval romance

"Guerrino the Wretch" (Guerrin Meschino in Italian) is a fifteenth-century romance recording for the first time in history the presence of the Apennine Sibyl on a remote peak of the Sibillini Mountain Range, with a description of the cave and its fairy inhabitants. In Italy, the tale of knight Guerrino and his amazing adventures was known and familiar to everybody: storytellers used to narrate his deeds in public squares, at the corners of the streets, in village fairs and open-air markets, and during town festivals. People were enthralled by the description of the knight's bravery, and the depiction of the eerie cavern and magical kingdom hidden beneath the rocky crest. And the fame of the cave travelled far and fast.

Un romanzo cavalleresco

"Guerrin Meschino" è un romanzo cavalleresco risalente al XV secolo, nel quale per la prima volta nella storia è registrata la presenza della Sibilla Appenninica su di una remota cima del massiccio dei Monti Sibillini, con una descrizione della grotta e dei suoi magici abitanti. In Italia, il racconto delle fantastiche avventure del cavaliere Guerrino erano ben note al pubblico popolare: i cantastorie erano infatti soliti narrare le sue gesta nelle pubbliche piazze, agli angoli delle strade, durante le fiere e i mercati nei villaggi, e in occasione delle festività religiose. La gente rimaneva estasiata di fronte al racconto delle imprese del coraggioso cavaliere, e soprattutto quando la narrazione prendeva a descrivere la sinistra caverna e il regno fatato nascosto al di sotto della cresta rocciosa. Così, la fama di quel cavaliere viaggiava rapida per ogni dove.

21 Feb 2016

Gauthier de Ruppes: the Crusader and the Sibyl's legend

It's the year 1422. Two years have elapsed after Antoine de La Sale's journey to Mount Sibyl, and the French gentleman is now in Rome: he is telling the tale of his adventurous travel to a certain Gauthier de Ruppes, «a knight from the Duchy of Bar». Sir de Ruppes questioned him «moult estroictement», very pressingly and in earnest. The reason was that he too had an experience to share about the Apennine Sibyl.

He «swore on his good faith and knighthood that his father's uncle used to say that he had passed a long time with the Sibyl», and that this uncle - after his return to France - had disappeared once again. Gauthier de Ruppes «creoit fermement» - was absolutely confident - that his relative had gone back «aux grans biens et plaisirs que il en disoit», to the rich wealth and pleasures which he had so frequently described and so sadly regretted, up there at the Sibyl's cave.

Why is this tale so meaningful? Because it shows us that de La Sale is not telling lies. He tells the truth.

Gauthier de Ruppes is a real gentleman, who existed in our actual world: he was the Earl of Trichastel and Soyes, the chamberlain of John the Duchy of Burgundy “The Fearless” and of his son Philip the Good. He was a most respected, well-known gentleman and knight who fought against the Ottomans during the Crusade that ended with the battle of Nicopolis in 1396: a Crusader.

Such important person was fully aware of the story about the Apennine Sibyl: a relation of his had been so bewitched by the legend so as to vanish altogether beneath that remote mountain in Italy. And he had found it convenient to discuss the matter with Antoine de La Sale, who had been at the Sibyl's site just a few years earlier.

A powerful legend. A captivating legend. A legend that was known throughout Europe. Even by Crusaders.

Gauthier de Ruppes: il Crociato e la leggenda della Sibilla

È l'anno 1422. Sono passati due anni dal viaggio di Antoine de La Sale al Monte Sibilla, e il gentiluomo provenzale si trova a Roma, a raccontare la sua esperienza ad un certo Gauthier de Ruppes, «cavaliere del ducato di Bar». Il signor de Ruppes lo interroga «moult estroictement», in maniera molto pressante e interessata. Perché anche lui ha avuto a che fare con la Sibilla Appenninica.

Egli, infatti, «giurava sulla sua buona fede e sull'ordine di cavaliere di avere avuto uno zio di suo padre che affermava esservi stato un lungo lasso di tempo»; dopo essere rientrato in Francia, questo parente era sparito di nuovo, e Gauthier de Ruppes «creoit fermement» - credeva fermamente – che egli fosse ritornato «aux grans biens et plaisirs que il en disoit», ai grandi beni e piaceri di cui aveva raccontato e che rimpiangeva spesso, lassù, alla Grotta della Sibilla.

Perché è importante questo racconto? Perché ci dimostra come de La Sale non stia mentendo. Egli racconta la verità.

Gauthier de Ruppes è un gentiluomo reale, realmente esistito: è stato signore di Trichastel e di Soyes, ciambellano e consigliere di Giovanni Duca di Borgogna, detto il “Senza Paura”, e del figlio Filippo il Buono. Si trattava di un nobile conosciuto e rispettato, un cavaliere che aveva combattuto contro gli Ottomani durante la Crociata che portò alla battaglia di Nicopolis nel 1396: egli era un Crociato.

Anche questo personaggio così importante ben conosceva la storia della Sibilla Appenninica, e addirittura un suo parente ne era rimasto così affascinato da sparire nelle viscere di quella remota montagna italiana. E aveva ritenuto di doverne discutere con Antoine de La Sale, che poco tempo prima si era recato proprio nei luoghi della Sibilla.

Una leggenda potente. Una leggenda affascinante. E conosciuta in tutta Europa. Anche dai cavalieri Crociati.

17 Nov 2015

De La Sale's ascent

Another route to Mount Sibyl leads to the cliff from the small hamlet of Montemonaco. That's the same route that Antoine de La Sale trod with horses and a retinue of peasants in 1420 when he climbed the mountain-side to visit the magical cave. A tortuous road goes up the flank of Mount Sibyl, with lots of bends and twists, up to the "Sibyl's Refuge", a resting place for hikers and bikers. From there on, the trail ascends the grassy mountain-side until it reaches the high crests leading straight to the Sibyl's peak.

As one walks the rocky ridges, looking down at the bottomless ravines standing on both sides, one remembers the words written by de La Sale centuries ago: «ne fault point qu’il face vent», you must hope for the wind not to blow too angrily, not to be flung into the abysses which present to your sight as open jaws.

L'ascesa di De La Sale

Dal piccolo villaggio di Montemonaco parte un altro sentiero verso il Monte Sibilla. Si tratta, in questo caso, dello stesso percorso scelto da Antoine de La Sale nel 1420, con il suo seguito di villici e di cavalli, quando egli decise di ascendere la montagna per visitare la magica grotta. Una tortuosa strada si snoda lungo il fianco del Monte Sibilla, con curve e controcurve, fino al “Rifugio Sibilla”, un luogo di sosta per escursionisti e mountain biker. Da lì in poi, il sentiero si inoltra lungo lo scosceso pendio erboso, fino a raggiungere le alte creste che conducono direttamente al picco della Sibilla.

Nel percorrere la dorsale rocciosa, osservando i precipizi senza fondo che si aprono su entrambi i lati del sentiero, tornano alla mente le parole scritte da Antoine de La Sale molti secoli fa: “occorre che non ci sia vento”, affinché non si corra il rischio di venire gettati nell'abisso infinito, che si apre di fronte ai nostri occhi come paurose fauci spalancate.

8 Nov 2015

Guerrino's trail

Here are the ridges leading to Mount Sibyl, at the far end of the picture towards the horizon. This is the same path as taken by the knight Guerrino The Wretch many hundreds of years ago. Loneliness mingled with uneasiness is the feeling while treading this sunny trail. The words written by H.P. Lovecraft in his "Supernatural Horror in Literature" come to mind: “the oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown”.

Il sentiero di Guerrino

Ecco le creste che conducono al Monte della Sibilla, visibile al limite dell'orizzonte in questa immagine. Questo, secondo la tradizione, è il percorso utilizzato anche da Guerrin Meschino, il cavaliere, oltre mille anni fa. Sentimenti di solitudine misti ad una inquieta aspettazione vi coglieranno mentre proseguirete lungo il sentiero immerso nel sole. E vi potranno tornare alla mente le parole scritte da H. P. Lovecraft nella sua opera “L'orrore del soprannaturale in letteratura”: “la più antica e la più intensa emozione che l'uomo possa provare è la paura, e la più grande paura è quella dell'ignoto”.

8 Oct 2015

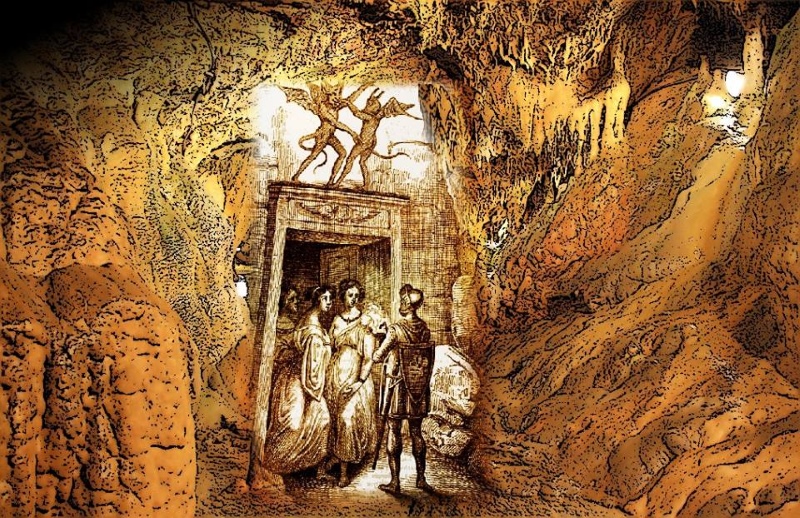

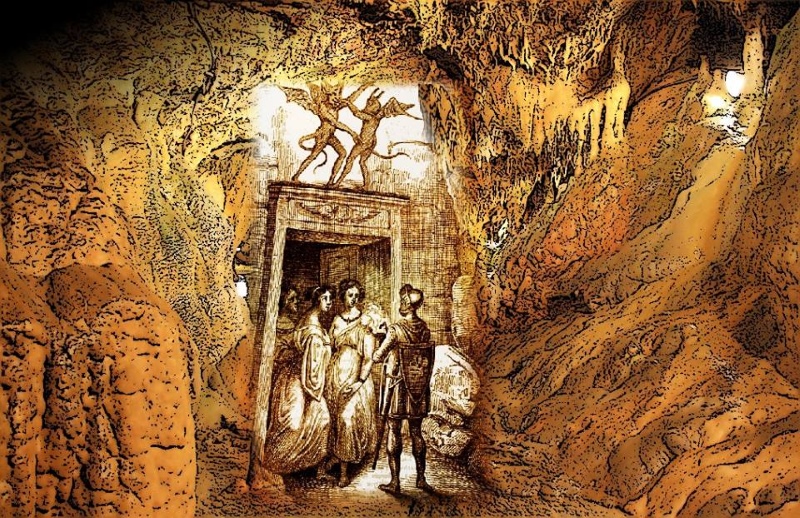

Exploring the Sibyl's cave

Mount Sibyl was also depicted as the hiding place of a sibilline oracle in another literary work: "Guerrino the Wretch" a fifteenth-century chivalric novel.

Guerrino, a valiant knight, ascended the eerie mountain while engaged in a long and hazardous quest, in search of his lost parents. He had come to know that a Sibyl resided in a cave on the mountain-top, and he was determined to reach her abode and interrogate her on his parents' identity and wherabouts.

No surprise that the tale recounted in "Guerrino the Wretch" is remarkably similar to that reported in Antoine de La Sale's "The Paradise of Queen Sibyl": we retrieve in Guerrino's story the same magical features and uncanny details.

In the darkness of the subterranean halls, Guerrino knocks at a door surmounted by statues of winged devils, and he gets a response: beatiful dames, the handsome Sibyl's servants open the door to him. And he can finally meet the Sibyl in her underground kingdom. A deadly hazrd, from which he will make only a narrow escape.

Esplorando la grotta della Sibilla

Anche in un'altra opera letteraria il Monte della Sibilla è descritto come il luogo nascosto dove si sarebbe rifugiato un oracolo sibillino: si tratta di “Guerrino il Meschino”, un romanzo cavalleresco del quindicesimo secolo.

Guerrino, valente cavaliere, si era recato sulla cima della strana montagna nel corso di un suo viaggio lungo e avventuroso, in cerca dei propri genitori perduti. Egli era venuto a conoscenza del fatto che una Sibilla si era stabilita all'interno di una caverna posta sulla cima, ed era intenzionato a raggiungerla per porle domande su chi fossero i suoi genitori e dove egli potesse trovarli.

Non ci sorprende la considerazione che il racconto narrato nel “Guerrin Meschino” sembra essere significativamente simile a quanto riportato da Antoine de La Sale nel suo “Il Paradiso della Regina Sibilla”: possiamo trovare nella storia di Guerrino i medesimi aspetti magici e gli stessi dettagli soprannaturali.

Nella tenebra delle stanze sotterranee, Guerrino aveva bussato ad una porta sormontata da statue di demoni alati: e una risposta era arrivata. Damigelle bellissime, le incantevoli dame del seguito della Sibilla, avevano aperto la porta a quel cavaliere.

Ed egli, finalmente, aveva potuto incontrare la Sibilla nel suo regno sotterraneo. Un rischio mortale, dal quale Guerrino riuscirà a sfuggire solamente con grande pericolo.

12 Sep 2015

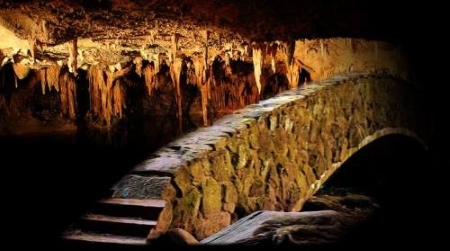

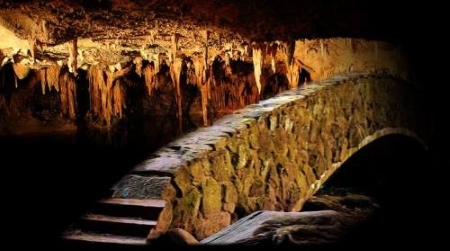

The ever slamming door

In the darkness of the cave, within the core of Mount Sibyl, the mystery continued to puzzle the minds of those who wanted to shed light on a legend which had achieved great renown throughout Europe. After crossing the bridge - De la Sale wrote in his "The Paradise of Queen Sibyl" - it had been reported that a huge gate was to be found, amid the cavern's pits and stalagmites. This gate had two doors made of glistening metal, which opened and closed with an unrelenting, perpetual motion, under a spell cast by the Sibyl. Only the brave could get through such a deadly trial, escaping a horrible death, crushed between the two gaping jaws of the gate. And beyond that gate...

Il portale che si spalanca e si chiude

Nell'oscurità della grotta, nelle viscere del Monte Sibilla, il mistero continuava ad affascinare le menti di coloro che intendevano gettare un fascio di luce su di una leggenda che aveva conquistato un fama enorme in tutta Europa. Dopo avere attraversato il ponte – scrisse de La Sale nel suo “Il Paradiso della Regina Sibilla” - i resoconti di precedenti viaggiatori raccontavano della presenza di una grande porta, incastonata tra le stalagmiti e i baratri della caverna. Questo portale era costituito da due battenti, costruiti in metallo scintillante, i quali si aprivano e si chiudevano con un movimento incessante, inarrestabile, sotto il controllo di un incantesimo lanciato dalla Sibilla. Solo i più coraggiosi avrebbero potuto superare questa prova mortale, evitando un'orribile morte, schiacciati tra le fauci spalancate del portale. E, oltre quella porta...

7 Sep 2015

The Sibyl's enchanted bridge

According to legend, the Apennine Sibyl, a prophetess and a divine being, lived inside the mountain, waiting for visitors. But what sort of subterranean path had to be taken to get to the cave's inner chambers and the palace of the Sibyl?

We have indications of what existed beneath the rock in the work by Antoine de La Sale, "The Paradise of Queen Sibyl", written in the fifteenth century. Treading the gloominess of the cavern was not only extremely hazardous: it was a sort of quest, in which the soul of men would be put under test. Only braveness and purity would succeed, just like in chivalric novels of the time.

After a sloping corridor going down in the bowels of the mount, the first trial was the magical bridge: in the darkness the visitor would run into a long bridge of rock crossing a ghastly abyss, from which the noise of gurgling subterranean waters was to be heard. The bridge was thin, remarkably thin: a wavering, uneasy step, and the unwary visitor would be hurled down into the black unfathomable gorge to meet his final fate in the cold waters.

But a strong heart made it possible to pass: the more the dauntless adventure advanced, the larger became the bridge, until the foot was able to reach the far end of the gorge. Ready to proceed towards more trials, and the encounter with the Sibyl.

Il magico ponte della Sibilla

Secondo la leggenda, la Sibilla Appenninica, un essere semidivino e dotato di capacità profetiche, viveva all'interno della montagna, in attesa. Ma quale percorso sotterraneo avrebbero dovuto intraprendere i visitatori per giungere fino alle stanze più segrete e al palazzo nascosto della Sibilla? Disponiamo di un'indicazione a proposito di ciò che esisteva sotto la cima del monte grazie all'opera di Antoine de La Sale, “Il Paradiso della Regina Sibilla”, un documento del quindicesimo secolo. Penetrare nella tenebra della caverna non solo era estremamente rischioso: si trattava anche di una sorta di “quest”, nel corso della quale l'anima del visitatore sarebbe stata sottoposta ad una serie di prove. Solamente il coraggio e la purezza avrebbero permesso di superarle, esattamente come nei romanzi cavallereschi dell'epoca.

Dopo un corridoio digradante verso le viscere della montagna, la prima prova era costituita da un ponte magico: nel buio il visitatore si sarebbe imbattuto in un lungo ponte di pietra, che si slanciava attraverso un abisso spaventoso, dal quale si poteva udire il suono di gorgoglianti acque sotterranee. Il ponte era sottile, particolarmente sottile: un passo esitante ed incauto, e il temerario visitatore sarebbe stato gettato nell'insondabile profondità del precipizio, verso una fine orribile tra le acque gelide.

Un cuore saldo, invece, sarebbe passato: a mano a mano che il coraggioso avventuriero si fosse avventurato lungo il ponte, questo sarebbe divenuto sempre più largo, finché il piede non avesse raggiunto l'altra estremità della gola. Pronto per inoltrarsi ulteriormente verso nuove prove, e verso l'incontro con la Sibilla.

30 Aug 2015

Inside the Sibyl's cave

Mount Sibyl, in Italy, was know throughout Europe because of the cavern present on its mountain-top. The cavern had possibly been an oracular center for thousands of years, well before the Romans established their rule on the region in 290 B.C.

More than a thousand years later, a French gentleman entered the cave and wrote an account of what he could see in the outer subterranean chamber. By the glow of his torchlight, Antoine de La Sale - himself a foreigner in Italy - noted a number of "carved inscriptions": they were names of foreigners as well, "Hans Wan Banborg", "Thomin Le Pons" and others.

Why people from far-off countries had come to Italy as far as that remote mountain and its cave? What secret was concealed under the huge mass of rock making up the mountain-top?

What they all were looking for? And why people are still coming to the Sibyl's peak in our present day?

An enigma is concealed under that mountain. And the enigma is still present today: in the same spot as several centuries ago.

All'interno della grotta della Sibilla

Un tempo, il Monte Sibilla, situato in Italia, era famoso in tutta Europa a causa della caverna che si apriva sulla cima. La grotta era stata forse un centro oracolare già da duemila anni, ben prima che i Romani stabilissero il proprio imperio nella zona nel 290 a.C.

Più di mille anni dopo, un gentiluomo francese sarebbe entrato in quella caverna e avrebbe scritto un resoconto di quanto aveva potuto osservare nella parte più esterna di quelle aule sotterranee. Alla luce della sua torcia, Antoine de La Sale – egli stesso uno straniero, un francese – avrebbe notato una serie di “iscrizioni incise”: si trattava di nomi di stranieri, “Hans Wan Banborg”, “Thomin Le Pons” e altri ancora.

Perché uomini provenienti da nazioni remote si erano recati in Italia fino a quella montagna perduta e alla sua grotta? Quale segreto era custodito al di sotto dell'enorme massa di roccia che formava quel monte?

Che cosa stavano cercando? E perché la gente continua a recarsi, ancora oggi, sul Monte della Sibilla?

Quella montagna nasconde un segreto. E l'enigma è ancora lì, ai nostri giorni: nello stesso identico punto, come molti secoli fa.

28 Aug 2015

A visit to the Sibyl dating to 1420

In 1420, a French gentleman, Antoine de La Sale, ascended Mount Sibyl. Why had he come from so distant a country to climb a peak hidden in the middle of the Apennine range in Italy? Six hundred years ago, the mount had already achieved its uncanny renown: Mr. de La Sale had been told that Mount Sibyl was the secret abode of a prophetess and priestess, the Apennine Sibyl.

A cave was on the top of the mount: it was the gateway to a subterranean kingdom, buried within the very core of the cliff. A maze of caverns and dark halls would provide access to a wonderful underground realm: fine palaces and damsels and gold were concealed under the rock.

He heard of all that. And he decided to go. And make his personal exploration into the matter.

He actually entered the cave.

Una visita alla Sibilla risalente al 1420

Nel 1420, un gentiluomo francese, Antoine de La Sale, saliva al Monte della Sibilla. Perché quest'uomo, venuto da una nazione così lontana, si era spinto fino ad ascendere un picco remoto, nascosto nel mezzo degli Appennini? Seicento anni fa, quella montagna aveva già conquistato la sua strana nomea: de La Sale aveva infatti udito il racconto di quella vetta, la quale avrebbe nascosto la residenza segreta di una profetessa e sacerdotessa, la Sibilla Appenninica.

Sulla cima si apriva l'imbocco di una grotta: si trattava della porta d'accesso ad un regno sotterraneo, sepolto al di sotto della roccia del monte. Un labirinto di cunicoli e aule tenebrose avrebbe dato accesso ad un meraviglioso regno ignoto: fantastici palazzi e bellissime damigelle e gemme preziose sarebbero stati nascosti nelle viscere della montagna.

Egli aveva udito tutto ciò. E aveva deciso di recarsi lassù, per indagare di persona quei luoghi.

E, effettivamente, riuscì ad entrare in quella grotta.