19 Apr 2020

Sibillini Mountain Range, the chthonian legend /8. A conclusive remark and a farewell

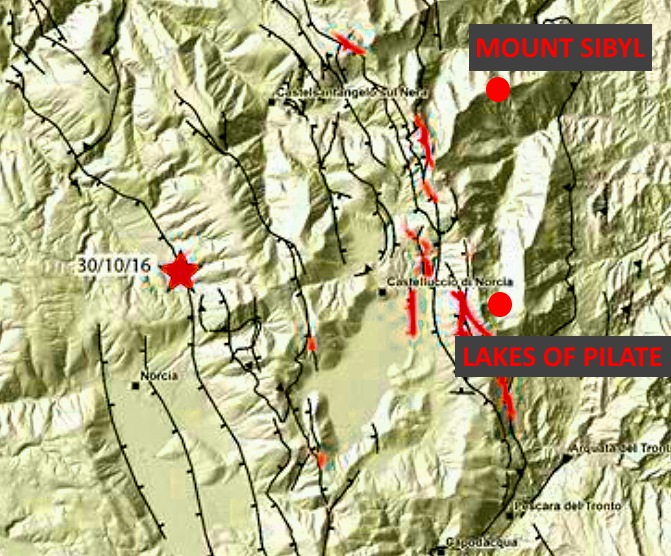

More than two years ago, in the wake of one of the largest earthquakes ever occurred in the territory of the Sibillini Mountain Range, the author of the present paper began to suppose that the legendary narratives which have been living in the area for centuries may actually be connected the to peculiar, seismic nature of the territory.

With the elaboration of a novel on the legend of the Apennine Sibyl (“The eleventh Sibyl”, 2010), we started to collect a large amount of literary information and data on the historical research on the mythical tales of the Sibillini Mountain Range, including most interesting material on the recurrent earthquakes which had plagued the land in the previous centuries. However, one patent fact could be noticed: no research information was available on the origin of the legendary tale of the Sibyl of the Apennines, while the narrative concerning the Lake of Pilate was manifestly connected to the known medieval legend of Pontius Pilate.

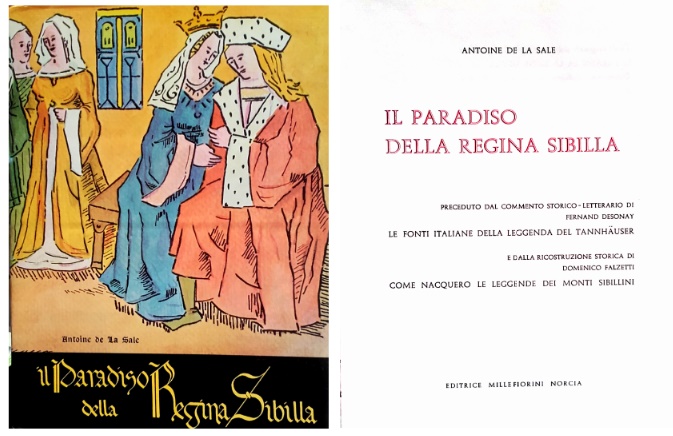

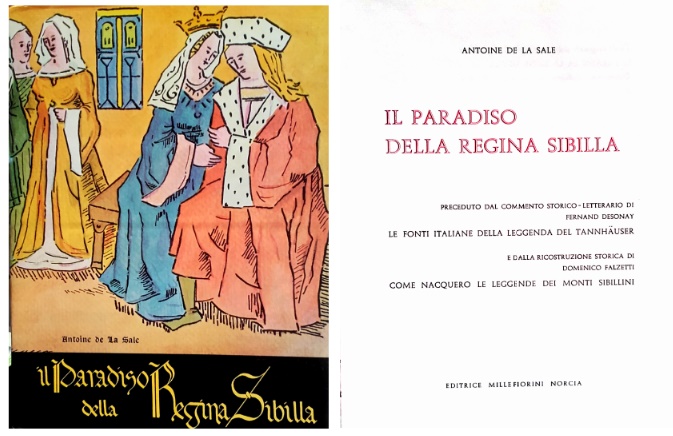

However, it seemed that the tale of the Apennine Sibyl had emerged from some sort of thick, impenetrable mist, and had manifested itself only in the fifteenth century, in the fascinating works written by Andrea da Barberino and Antoine de la Sale: “Guerrino the Wretch” and “The Paradise of Queen Sibyl”.

Nobody had ever investigated what had happened in earlier times, and whether that Sibyl could be traced across the centuries of the Middle Ages. Only one thing seemed to be clear to scholars: the Apennine Sibyl was not included in the classical list of Sibyls, nor any reference to such a Sibyl had ever been retrieved in Roman or early-Christian literature.

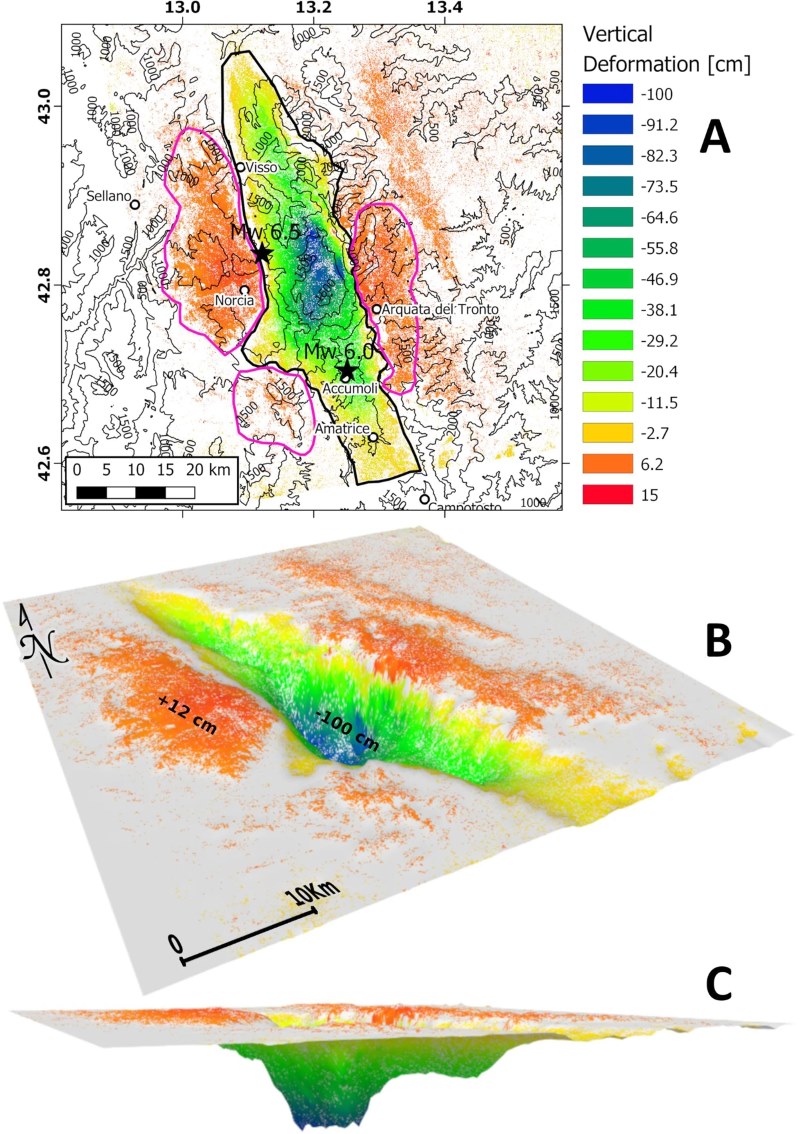

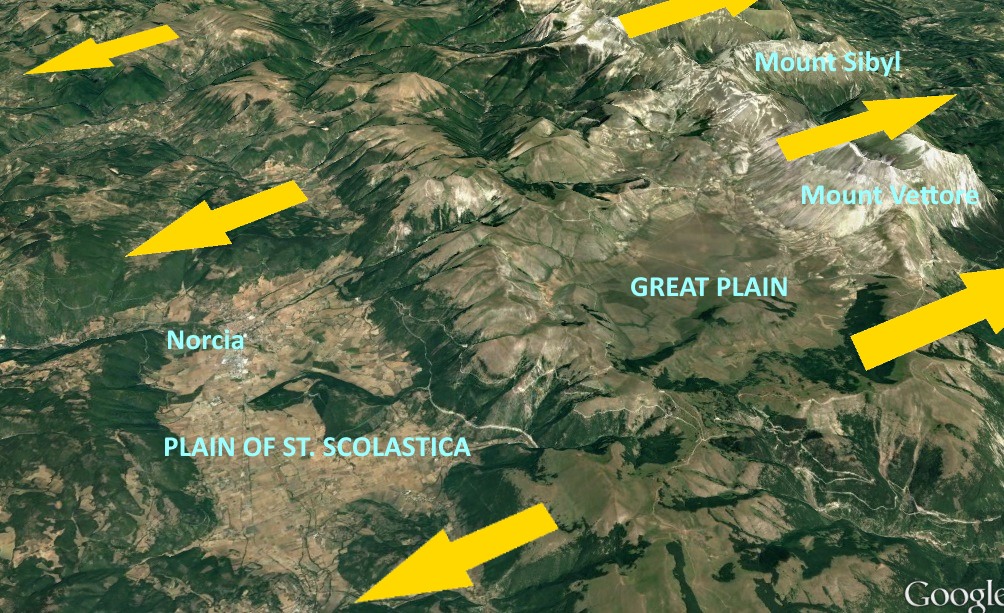

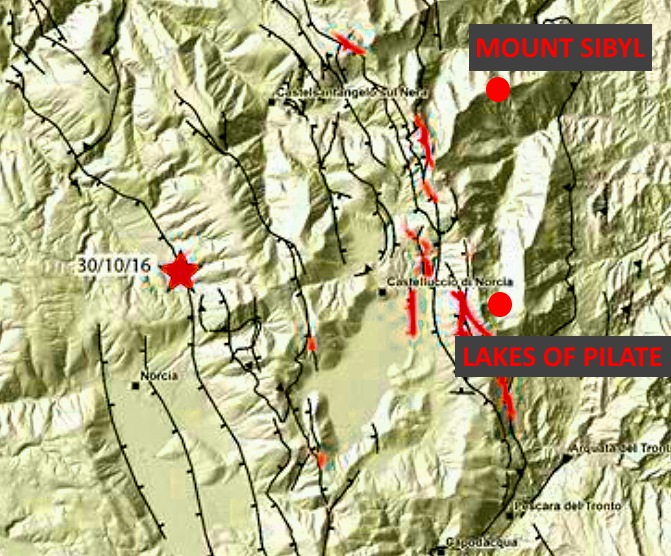

But when, once again, the earthquakes hit the Sibillini Mountain Range in the year 2016, the mighty effects that were visible on the mountainsides and the sheer terror experienced by the local residents under the long sequence of ghastly shocks, suggested a new course of investigation.

A course that no scholar, in the past two centuries, had ever addressed.

The potential of the Sibillini Mountain Range as a generator of mythical tales connected to the nature and origin of the earthquakes was becoming apparent, especially when considered in a context of ancient pre-Roman populations inhabiting the area in a long-gone past.

However, this research topic could not be analysed and developed without addressing, in the first instance, the question of a potential medieval origin and evolution of the legends concerning the Sibyl's Cave and the Lake of Pilate. This was a research step that was mandatorily required to bridge the considerable gap which was patently visible between the fifteenth-century literary witnesses available to us and any potential conjecture on a Roman or even pre-Roman original core of the myth inhabiting the Sibillini Mountain Range.

So in December 2017 we began to investigate the centuries before the fifteenth in further depth, in search of clues that might hint to a presence of our Apennine Sibyl across the medieval age. And the search was instantly rewarding.

We immediately stumbled upon a passage written by Ferdinando Neri, in his “The Italian traditions of the Sibyl” (“Le tradizioni italiane della Sibilla”, 1913), in which the Italian scholar mentioned the «ever-slamming metal doors» that are present in the popular lore connected to visits to supernatural 'netherworlds': the same kind of otherwordly device which is depicted by Antoine de la Sale in his description of the Sibyl's Cave.

This opened the way to the first valuable finds of inherited literary themes and narrative topics in earlier chivalric works, such as “Huon of Bordeaux” and “Huon d'Auvergne”, and to preliminary observations concerning a possible link to other otherwordly narratives, like the tale on the Purgatory of St. Patrick and the Cumaen Hades.

Otherworld turned to be one of the main keywords in the legendary framework of the Sibillini Mountain Range: at the beginning of the year 2018, we could release two papers (“Antoine de La Sale and the magical bridge concealed beneath Mount Sibyl” and “The literary truth about the magical doors in 'The Paradise of Queen Sibyl')” which proved the illustrious literary lineage of the otherwordly devices that Antoine de la Sale had reported as present within the Sibyl's Cave.

Following a successive series of articles, in January 2019 a further landmark paper was released (“Birth of a Sibyl: the medieval connection”), in which the literary character of the Apennine Sibyl was traced back to Morgan le Fay and her companion Sebile, the necromantic figures which fully belong to the medieval tradition of the Matter of Britain and the Arthurian cycle. In May 2019, another paper (“A legend for a Roman prefect: the Lakes of Pontius Pilate”) provided a full, comprehensive summary of the antique legend concerning the burial place of Pontius Pilate, a foreign tale that had possibly deposited itself amid the Sibillini Mountain Range during the fourteenth century, as specific details seemed to suggest.

As a result of the above research, the Sibyl of the Apennines and the Roman prefect could be positively considered as overlays, or additional legendary layers that had established themselves in central Italy during the High Middle Ages.

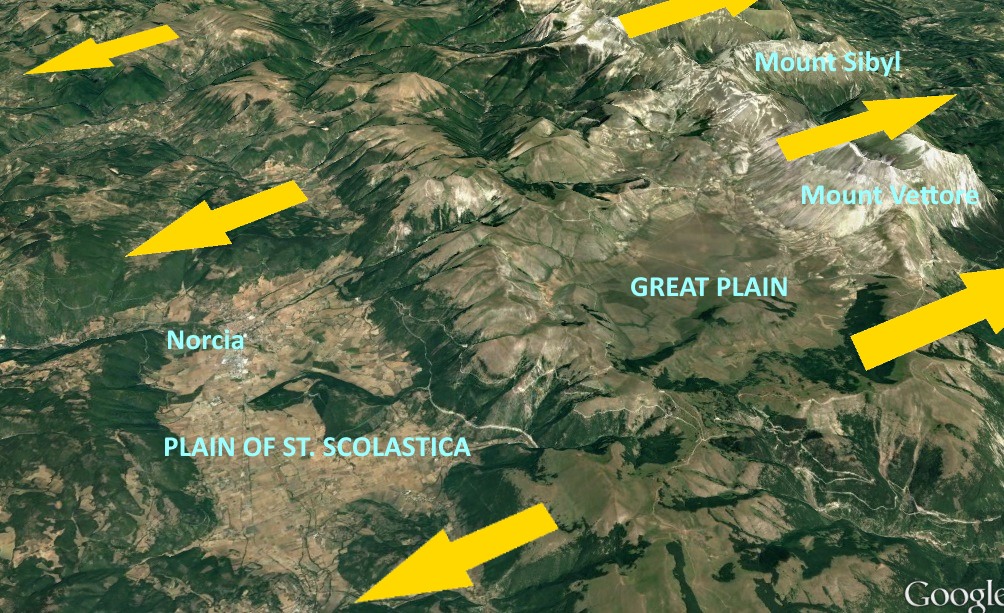

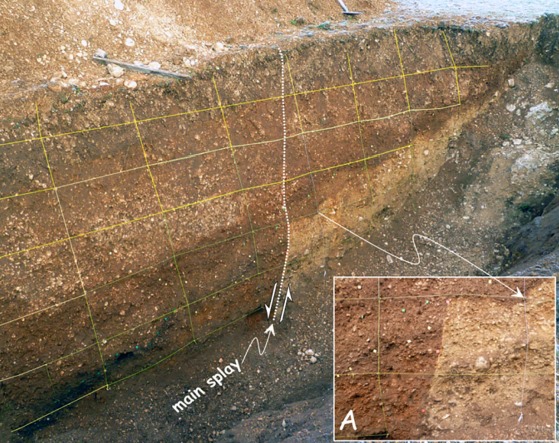

In September 2019, with the paper “Sibillini Mountain Range: the legend before the legends”, we explored and identified the common legendary traits which appear to lie beneath the mentioned overlays, with reference to both geographical features, the Lake and the Cave: necromancy, a demonic presence, tempests and devastation arising from the two sites (Fig. 1).

A fourth, major common aspect was fully detected and analysed in the subsequent paper (“Sibillini Mountain Range, a cave and lake to the Otherworld”): the possible role of both sites as legendary passageways to the Otherworld, an illustrious literary topic which, in the Western world, spans from the “Odyssey” to the “Aeneid”, and then to various early-Christian and medieval visions accounting for legendary visits to a realm of dead or a demonic Hell. Manifest narrative contaminations could be retrieved between the legends of the Sibillini Mountain Range and the otherwordly narratives concerning a classical entryway in Cumae, in southern Italy, and Lough Derg, the Irish entrance to the Purgatory of St. Patrick.

Throughout the whole investigation, it was patent the mighty attractive force exerted by the Lake and Cave set within the Sibillini Mountain Range on different, extraneous legendary material, coming from far-off lands and countries: Morgan and Sebile, Pontius Pilate, the Cumaean Sibyl and the Purgatory of St. Patrick.

With the present, conclusive paper, we investigated, at last, the inner, original core of the legends which inhabit the Sibillini Mountain Range, now finally deprived of all the additional legendary layers that have deposited themeselves on this area, under the attraction of a most powerful mythical engine.

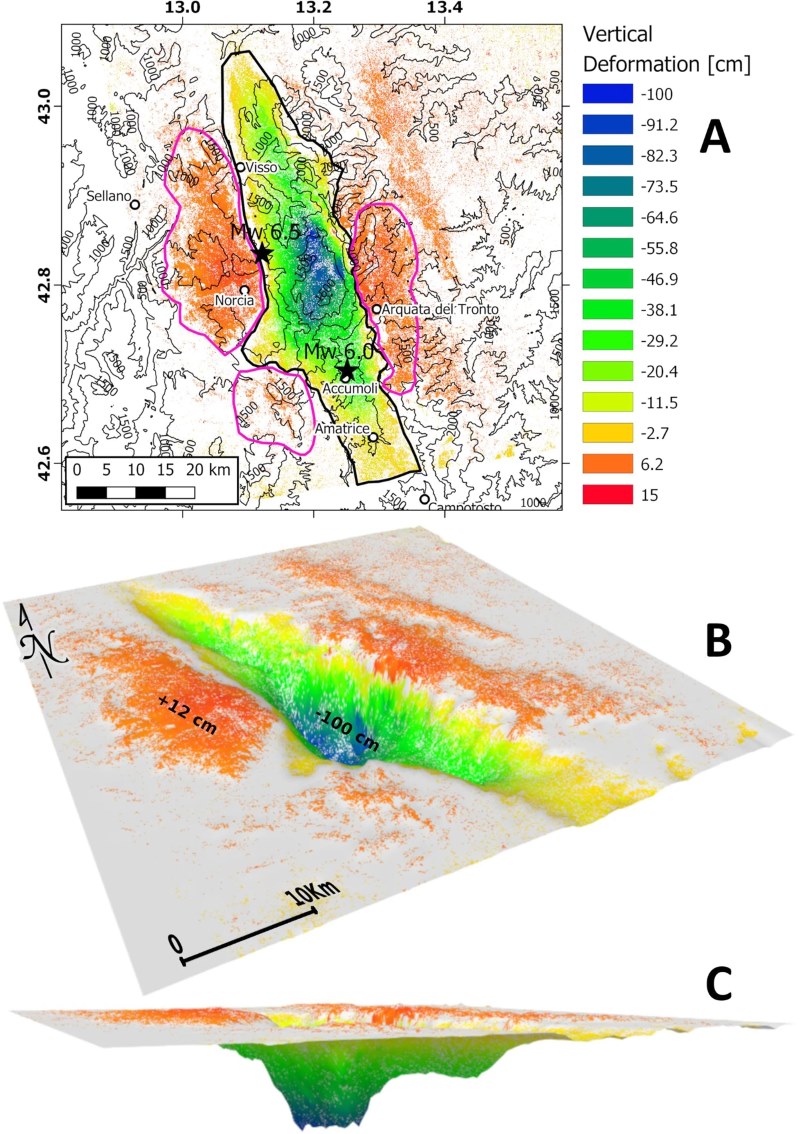

And the engine, the legendary dream set at the very base of all this is earthquakes (Fig. 2).

We conjectured that the pre-Roman inhabitants of the Sibillini Mountain Range feared the earthquakes the way as we fear them today. However, the tools available to them to understand the appalling phenomenon which recurrently struck them with the utmost might were markedly different from ours. Our contemporary scientific knowledge helps us in the control of our fears. Instead, the ancient populations of Sabines and Picenes could only resort to myth, with the generation of legendary narratives.

Such narratives are wholly lost to us. Nonetheless, we may try to conjecture what sort of dreams they might have housed in their hearts before the appalling, harrowing potency of the earthquakes. A possible dream of demons, whose abode was beneath the mountain. The need for a contact, perhaps, with a view to ask for mercy and salvation. The eerie, sinister Lake and Cave as the most natural choices where to establish such hypothetical otherwordly contact. Physical points of access to a subterranean Otherworld, inhabited by supernatural, fiendish beings. Two 'hot spots' set amid precipitous mountains. Landmarks to legend.

This is, in our opinion, the wondrous thickness and amazing richness of the legendary framework which marks this most beautiful, most charming, absolutely outstanding land of central Italy: the Sibillini Mountain Range. A mythical abundance and wealth which is rarely achieved by other regions in the world.

As a final remark, we want to stress the fact that, amid the other landmarks to otherwordly passageways that antique legendary traditions have consigned to us, the Sibillini Mountain Range is certainly the less unfounded, the less fairy-like and for sure the most justified and understandable, mythical as it may be.

Because, if the Hades set in the caves of Cumae is merely linked to the volcanic nature of the place and the poisonous gases which filled those hollows, and the Purgatory of St. Patrick was just a sort of cellar for dupes, duly exhausted prior to their visit and then locked up within a small, oxygen-deprived space, the Sibillini Mountain Range was a place where terror actually ruled, and a demonic presence was tangibly clear and present throughout the years and the centuries: a true Otherworld of earthquakes.

It is in this very framework that the true significance of the ancient name of the Sibillini Mountain Range, as reported by Vergil in his “Aeneid”, may become totally apparent to our contemporary perception: «Tetricae horrentis rupes», writes the great Latin author, «dreadful, sullen, gloomy cliff», a land of eerie mystery. And terror.

However, across the centuries people have only been aware of the renown of Lake Avernus in Cumae and Lough Dergh in Ireland. It is now time to bestow on the Sibillini Mountain Range the fame and merit it deserves, out of the astounding quality and underlying substance of its legend.

Of course, the conjectural scenario presented in this paper will need further confirmations.

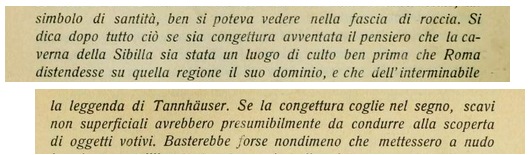

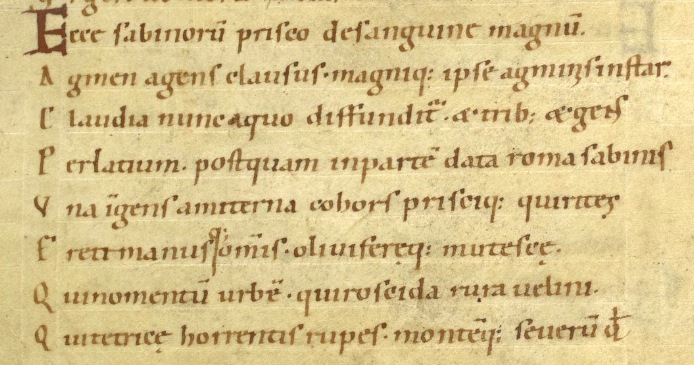

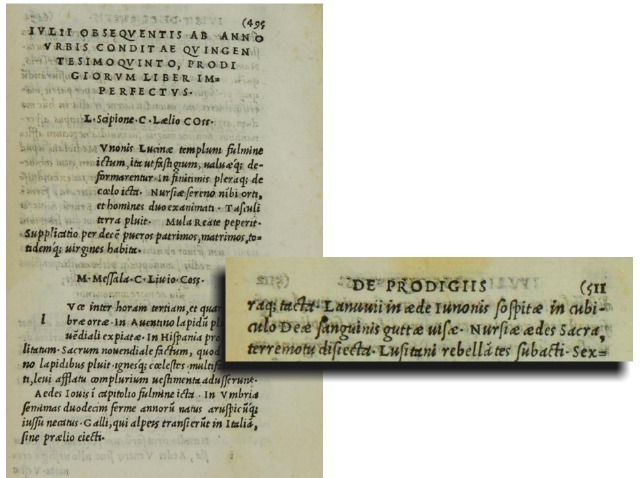

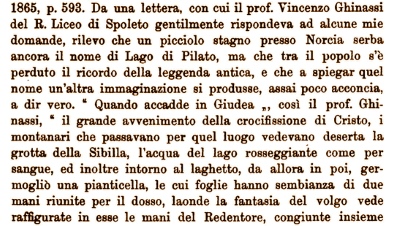

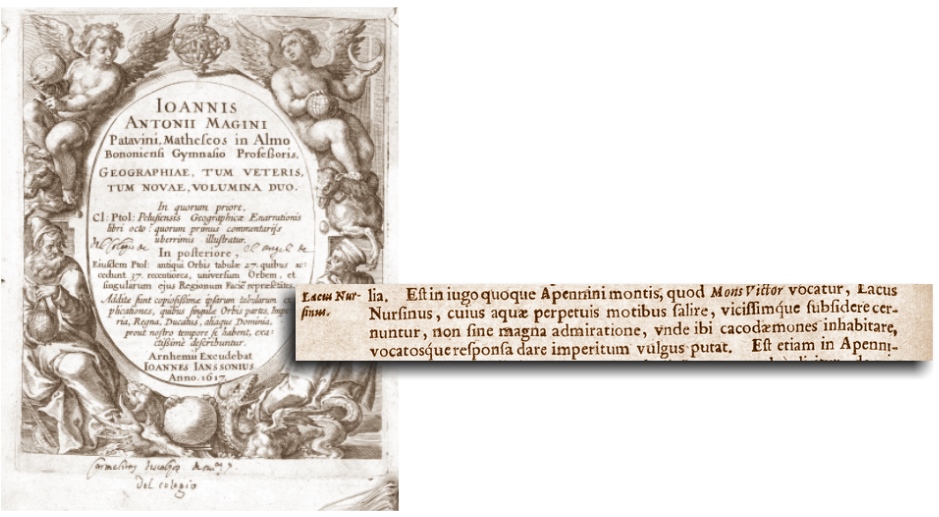

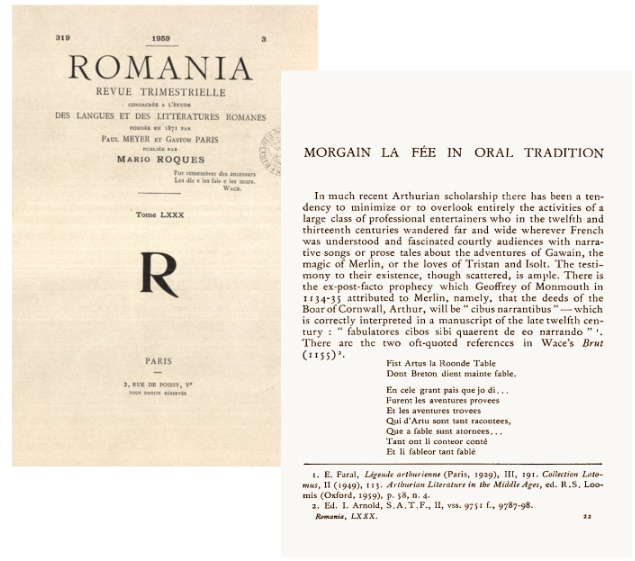

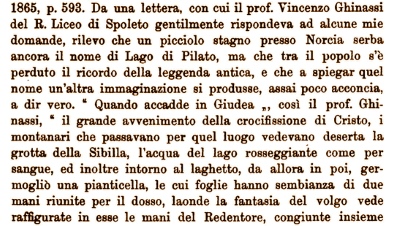

We do not know whether future potential excavations at the Lake and Cave might possibly ascertain the presence of any remnants of the hypothetical highland shrines we envisaged, in the forms of votive offerings or even bone remains deposited at the two sites across the centuries of the Iron Age. Sure enough, if any such remnant still exists, it is buried beneath many feet of debris and rubble at the bottom of the Lake, and thick layers of collapsed rocks within the Cave, or even in unreachable pits down in the same Cave. However, we fully subscribe to the reasearch line already envisaged by Pio Rajna, the Italian philologist, in 1912 (Fig. 3):

«Our considerations suggest that the idea that the Sibyl's cave may have been a site of worship well before Rome established its rule over that region is not a daring assumption [...] If our conjecture is correct, deeper excavations may possibly lead to the unearthing of votive offerings».

[In the original Italian text: «Si dica dopo tutto ciò se sia congettura avventata il pensiero che la caverna della Sibilla sia stata un luogo di culto ben prima che Roma distendesse su quella regione il suo dominio [...] Se la congettura coglie nel segno, scavi non superficiali avrebbero presumibilmente da condurre alla scoperta di oggetti votivi»].

But the major and most significant portion of the future researches on the Sibillini Mountain Range will rest, in our opinion, upon further historical and archeological investigations on the culture and beliefs of the Sabines and Picenes, in connection with the fact that additional, deeper enquiries at many sites across and around the Sibillini Mountain Range are still needed.

So our long travel through the fascinating legends that are found in the very heart of Italy, immersed in the gorgeous scenery of the Sibillini Mountain Range, is nearing its end.

As in a sort of 'reverse engineering' process, we have unravelled the thorny tangle of different legends which makes up the complex legendary system that lives on the cliffs of central Apennine, in Italy. To perform this challenging, stimulating task we have retraced backwards the legendary, intertwined threads that centuries have been weaving over these amazing mountains.

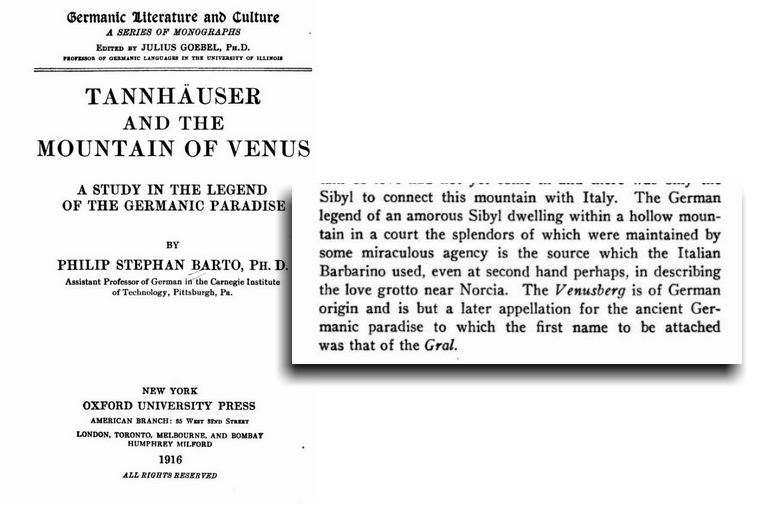

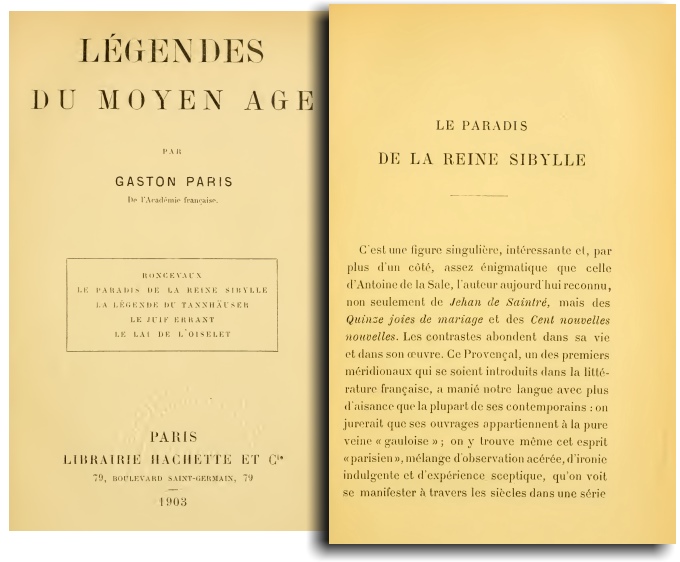

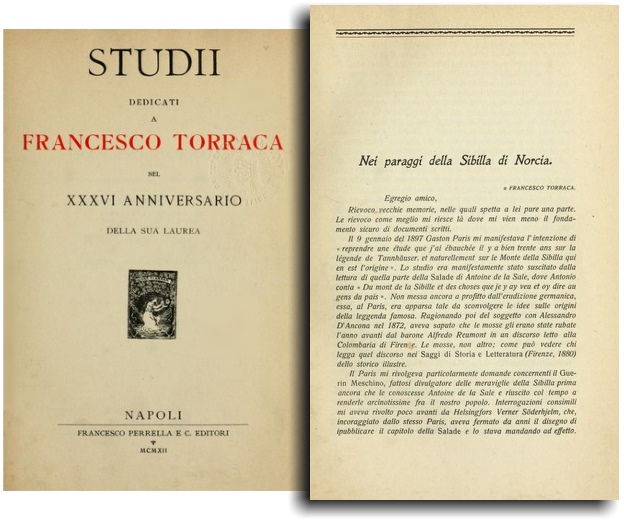

We are proud to have been part of a long, illustrious chain of scholars who, across one hundred fifty years, have confronted with the enigmatic questions posed by the legendary tales of the Apennine Sibyl and the Lake of Pilate, in search of a truth that was so charming and at the same time so elusive. We had the chance to share the same dreams that other great academics, philologists and men of letters have housed in their hearts: from Alfred von Reumont to Arturo Graf, from Gaston Paris to Pio Rajna, from Lucy Ann Paton to Ferdinando Neri, and then Roger S. Loomis, Fernand Desonay, Domenico Falzetti, and Luigi Paolucci, a brilliant mind who was so keen as to pinpoint, neatly and confidently, the right course that research had to adopt to solve this legendary riddle.

They all were fascinated by the spell which hovers around the lofty peaks of the Sibillini Mountain Range. Many of them had a lifelong dream in their soul: they wanted to find a solution to the enigma. And yet, they did not possess the right key, the very peculiar one that unlocked the door to the inner core of the mystery. A deeper understanding, which can only be reached by those who know, even by direct experience, what an earthquake is.

And we are sure that, if we had now the chance to speak to them, their eyes would shine with riveted amazement, while listening to a conjecture which provides comprehensive answers to many of the questions they happened to pose to themselves as to the legends of the Sibillini Mountains Range. Because we have provided a possible, motivated answer to the most fundamental question of all, the question that a philologist, Paolo Toschi, and his brilliant pupil, Luigi Paolucci, stated many decades ago:

«Why were these very places, and not different ones, inhabited by the Sibyl, and why did necromancers use to come here to consecrate their spellbooks?».

[In the original Italian text: «Ma perché proprio in questi determinati luoghi e non in altri abitava la Sibilla, e i maghi vengono a consacrare il libro del Comando?»].

This is the very same question we posed to ourselves during our search, when we stated it in our previous papers “Birth of a Sibyl: the medieval connection” and “A legend for a Roman prefect: the Lakes of Pontius Pilate”: what sort of magnetic pull did attract so many magical, estraneous legendary narratives on the peaks of Mount Vettore and Mount Sibyl? For what kind of fated chance did an Apennine Sibyl and a Roman prefect, accompanied by eerie tales about devastating storms, come to rest, like a ball spinning on a roulette wheel, right into the position marked by these remote Italian mountains?

At that time, we had already begun to repute that so mighty a pull might arise from some odd condensation of any peculiar nature of this region, the Sibillini Mountain Range; an effect generated by some unknown local factor, a result of the physical peculiarities of this wondrous territory: peculiarities which rendered it able to generate a powerful mythical attraction for highly-emotional legendary narratives.

And the specific peculiarity of this land, the Sibillini Mountain Range, is earthquakes.

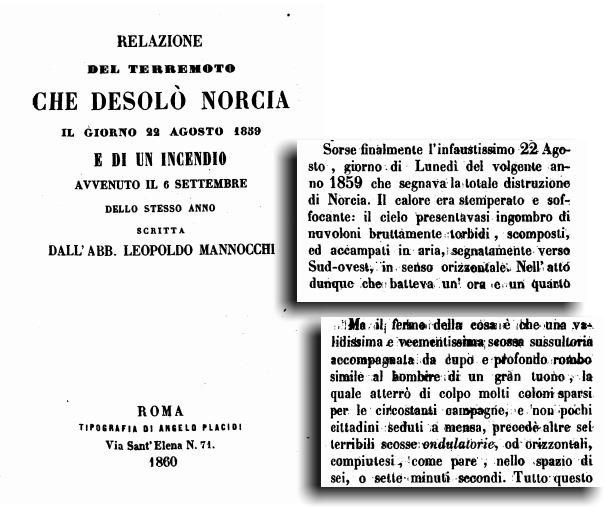

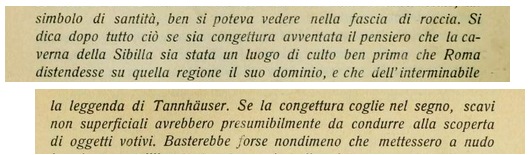

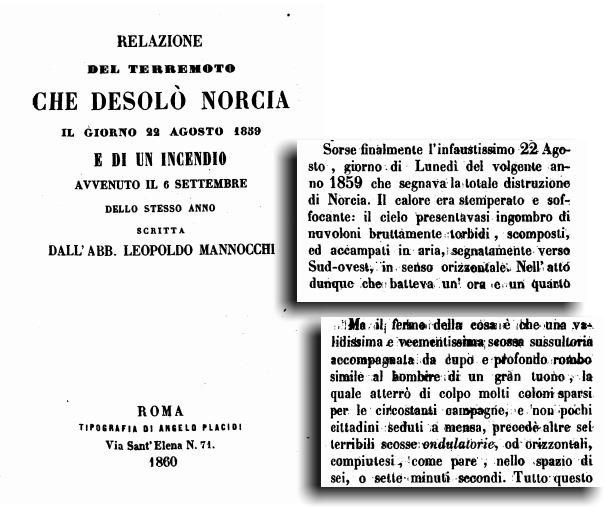

Earthquakes: «the most horrible event that the world we inhabit offers to our sight», as Leopoldo Mannocchi wrote in 1859, «a thoroughly frightful scourge, which many times has struck and ruined this town [Norcia]» (Fig. 4).

[In the original Italian text: «il più terribile dei fenomeni che sottoponga a' nostri sguardi il pianeta da noi abitato, il paurosissimo flagello del tremuoto, che assai volte avea costernata e concussa questa città»].

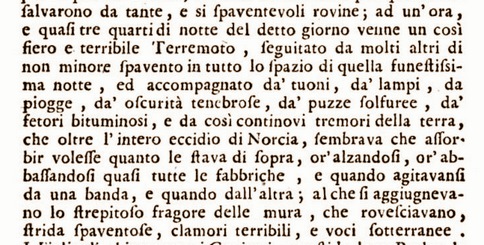

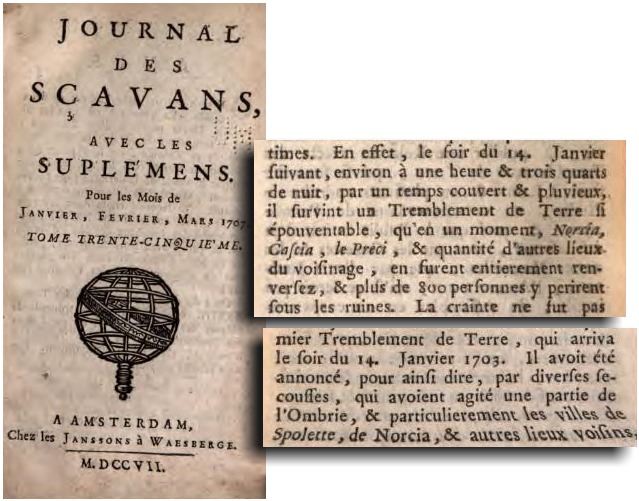

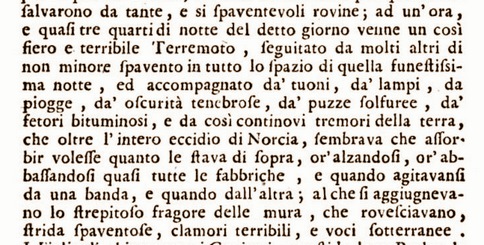

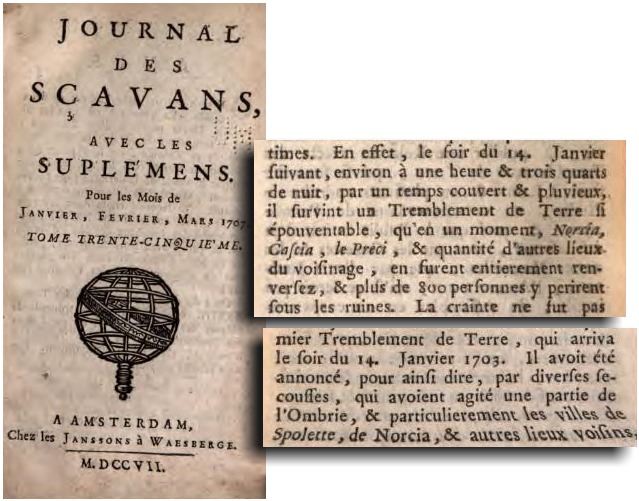

An horrifying event, which is so heinous as to give origin to such hair-raising descriptions as we find in the chronicles concerning the devastating earthquake that occurred in the year 1703 (Fig. 5):

«At 1:45 in the night of the said day, so fierce and terrifying an Earthquake came, followed by many others, as frightful as the first tremblor, across the whole duration of that grievous night, and accompanied by thunderbolts, lightnings, sulphurous smells, and by so many ceaseless shakes of the ground, that in addition to the whole destruction of Norcia, it seemed that it was determined to swallow everything in the land above, now swelling and then subsiding together with all the buildings, and then swaying from one side to the other; this havoc was multiplied by the roaring noise of the collapsing walls, blood-curdling wails, direful outcries, voices coming from beneath the ruins».

[In the original Italian text: «Ad un'ora, e quasi tre quarti di notte del detto giorno venne un così fiero e terribile Terremoto, seguitato da molti altri di non minore spavento in tutto lo spazio di quella funestissima notte, ed accompagnato da' tuoni, da' lampi, da fetori bituminosi, e da così continovi tremori della terra, che oltre l'intero eccidio di Norcia, sembrava che assorbir volesse quanto le stava di sopra, or'alzandosi, or'abbassandosi quasi tutte le fabbriche, e quando agitavansi da una banda, e quando dall'altra; al che si aggiugnevano lo strepitoso fragore delle mura, che rovesciavano, strida spaventose, clamori terribili, e voci sotterranee»].

Life and death, bodily existence and supernatural powers, mortality and fiendish divinity: the basical hopes and terrors which are housed in the hearts of men and women found a most fit abode at this small portion of Italy and Europe.

So our work is completed. It is now up to scholars and researchers to continue along the path we have traced, or to reject it.

We only want to add one more, and final, consideration.

Maybe the model we set down, involving earthquakes and legendary demons presiding over them, may sound as preposterous, and even somewhat foolhardy, if not utterly foolish.

To this sort of criticism, we do not intend to reply by putting forward, again, the many considerations we already presented in this research paper.

We just intend to provide a different, far more effective answer.

Because, in the year 2016, as we already know, many mighty earthquakes struck the Sibillini Mountain Range.

And on November, 28th 2019, three years later, the Italian news agency ANSA released a number of interviews recorded by a local correspondent, Gianluigi Basilietti, at Castelluccio di Norcia, the small hamlet set in the middle of the region, a settlement that was entirely demolished by the terrific seismic waves (Fig. 6).

A man was interviewed. An elderly man, who was born in Castelluccio and, though now living in Rome, had resided for most of his life before the precipitous versants of Mount Vettore. He was a man of our present times, so what he said is only a faint shadow of the feelings that the ancient inhabitants of the Sibillini Mountain Range may have housed in their hearts in a far-away antiquity, when the earthquake hit their dwellings and land with its utmost potency.

And yet, his words, though uttered by contemporary lips, were thoroughly impressive:

«... Suddenly, a Fiend arrives from underneath», he said, «and tears down everything» (in the original Italian words: «... poi arriva il Diavolo sotto, e sfascia tutto»).

A Fiend arrives, from beneath. And devastates the whole land.

The Iron Age, in the Sibillini Mountain Range, suddenly seems to reach out to us through an unfathomable span of time: on the eerie, divine, terrifying waves of earthquakes.

Monti Sibillini, la leggenda ctonia /8. Una considerazione e un saluto conclusivi

Più di due anni fa, dopo uno dei più potenti terremoti mai occorsi nel territorio dei Monti Sibillini, l'autore del presente lavoro di ricerca ha cominciato a ipotizzare come le narrazioni leggendarie che per secoli hanno abitato quest'area possano essere in realtà connesse con la peculiare natura sismica del territorio.

Con l'elaborazione di un romanzo sulla leggenda della Sibilla Appenninica ("L'undicesima Sibilla", 2010), avevamo cominciato a raccogliere una vasta mole di informazioni storiche e riferimenti letterari in relazione ai racconti mitici dei Monti Sibillini, incluso anche materiale particolarmente interessante concernente i terremoti che, in modo ricorrente, avevano colpito quel territorio nei secoli precedenti.

Una considerazione assai evidente poteva, però, essere evidenziata sin dall'inizio: nessuna ricerca scientifica risultava essere disponibile in relazione all'origine del racconto leggendario riguardante la Sibilla degli Appennini, mentre era chiaro sin da una prima analisi come la narrazione concernente il Lago di Pilato fosse manifestamente connessa alla ben nota leggenda medievale relativa a Ponzio Pilato.

Sembrava, dunque, che il racconto della Sibilla Appenninica fosse apparso emergendo da una sorta di fitta, impenetrabile nebbia, manifestandosi solamente nel quindicesimo secolo, nelle affascinanti opere vergate da Andrea da Barberino e Antoine de la Sale: "Guerrin Meschino" e "Il Paradiso della Regina Sibilla".

Nessuno aveva mai condotto alcuna investigazione a proposito di ciò che era avvenuto precedentemente, e se l'origine di quella Sibilla potesse essere rintracciata attraverso i secoli del medioevo. Solo un fatto pareva essere chiaro agli studiosi: la Sibilla Appenninica non era compresa nell'elencazione classica delle Sibille, né alcun riferimento a tale Sibilla poteva essere rivenuto nella letteratura latina o protocristiana.

Ma quando, ancora una volta, i terremoti colpirono i Monti Sibillini nell'anno 2016, i potenti effetti che si erano palesati sui fianchi delle montagne e il profondo terrore esperimentato dalla popolazione residente, sottoposto alla lunga sequenza di spaventose scosse, non poteva che suggerire una nuova strategia di investigazione.

Una strategia che nessuno studioso, negli ultimi due secoli, aveva mai delineato.

Il potenziale del massiccio dei Monti Sibillini come generatore di racconti mitici connessi alla natura e all'origine dei terremoti stava diventando evidente, specialmente se considerato nel contesto storico e culturale relativo alle antiche popolazioni preromane che abitarono quest'area in un passato particolarmente remoto.

Nondimeno, questa problematica di ricerca non avrebbe potuto essere analizzata e sviluppata senza prima affrontare la questione della possibile origine medievale e dell'evoluzione nel tempo delle leggende relative alla Grotta della Sibilla e al Lago di Pilato. Si trattava di uno stadio della ricerca con il quale occorreva necessariamente misurarsi al fine di colmare il vuoto che risultava essere palesemente visibile tra le testimonianze letterarie quattrocentesche a noi disponibili e qualsivoglia possibile congettura su un potenziale nucleo originale romano, o addirittura preromano, del mito che abita i Monti Sibillini.

Così, nel dicembre 2017 abbiamo cominciato a investigare in specifico dettaglio i secoli che precedono il quindicesimo, in cerca di indizi che potessero segnalare la presenza della nostra Sibilla Appenninica attraverso l'età medievale. E la ricerca si presentò immediatamente come assai feconda.

Potemmo subito imbatterci, infatti, in un passaggio scritto da Ferdinando Neri, nel suo volume "Le tradizioni italiane della Sibilla" (1913), nel quale lo studioso italiano menzionava le «porte di metallo, che battono continuamente» in quanto presenti nelle tradizioni popolari connesse a visite condotte all'interno di sovrannaturali 'mondi sotterra': lo stesso genere di meccanismo oltremondano illustrato da Antoine de la Sale nella sua descrizione della Grotta della Sibilla.

Questo indizio ha aperto la strada ai primi rilevanti ritrovamenti di temi letterari e situazioni narrative ereditati da precedenti opere cavalleresche, quali "Huon di Bordeaux " e "Ugone d'Alvernia", e a osservazioni preliminari concernenti un possibile collegamento con altre narrazioni oltremondane, come il racconto del Purgatorio di San Patrizio e l'Ade cumano.

'Aldilà'' si è rivelata essere una delle parole-chiave per l'interpretazione del leggendario contesto che abita i Monti Sibillini: all'inizio dell'anno 2018, è stato possibile pubblicare due articoli ("Antoine de La Sale e il magico ponte nascosto nel Monte della Sibilla" e "La verità letteraria sulle magiche porte nel 'Paradiso della Regina Sibilla'"), nei quali è stata delineata l'illustre ascendenza letteraria dei meccanismi oltremondani che Antoine de la Sale aveva riferito essere presenti all'interno della Grotta della Sibilla.

A valle di una successiva serie di articoli, nel gennaio 2019 veniva pubblicata un'ulteriore fondamentale ricerca ("Nascita di una Sibilla: la traccia medievale"), nella quale si evidenziava il collegamento del personaggio letterario della Sibilla Appenninica con Morgana la Fata e la sua compagna Sebile, due figure negromantiche che appartengono pienamente alla tradizione medievale della Materia di Bretagna e del ciclo arturiano. Nel maggio 2019, un altra ricerca ("Una leggenda per un prefetto romano: i Laghi di Ponzio Pilato") forniva un'esaustiva ricapitolazione dell'antica leggenda concernente il luogo di sepoltura di Ponzio Pilato, un racconto palesemente estraneo che era venuto a depositarsi tra i Monti Sibillini probabilmente nel quattordicesimo secolo, come alcuni specifici dettagli sembrerebbero suggerire.

Come risultato delle citate ricerche, la Sibilla degli Appennini e il prefetto romano potevano essere fondatamente considerati come sovrastrutture, o livelli leggendari aggiuntivi, stabilitisi nell'Italia centrale durante il medioevo.

Nel settembre 2019, con l'articolo "Monti Sibillini: la leggenda prima delle leggende", abbiamo esplorato ed evidenziato i tratti leggendari comuni che sembrano situarsi al di sotto delle predette sovrastrutture, in riferimento ad entrambi gli elementi naturali, il Lago e la Grotta: negromanzia, una presenza demoniaca, tempeste e devastazioni insorgenti da ambedue i siti (Fig. 1).

Un quarto aspetto condiviso, di fondamentale importanza, è stato completamente delineato e analizzato nel successivo articolo ("Monti Sibillini, un Lago e una Grotta come accesso oltremondano"): il possibile ruolo di entrambi i siti in qualità di leggendari passaggi verso una regione oltremondana, un illustre tema letterario che, nel mondo occidentale, partendo dall'"Odissea" e dall'"Eneide", giunge fino alle numerose visioni cristiane e medievali che narrano di leggendarie visite al regno dei morti o presso demoniache regioni infernali. Palesi contaminazioni narrative possono essere infatti rinvenute tra le leggende dei Monti Sibillini e i racconti oltremondani riguardanti un classico punto di passaggio in Cuma, nel meridione d'Italia, e Lough Derg, l'ingresso irlandese al Purgatorio di San Patrizio.

Con il procedere dell'intera investigazione, è risultata manifesta la potente capacità attrattiva esercitata dal Lago e dalla Grotta, situati tra i Monti Sibillini, nei confronti di materiale leggendario diverso ed estraneo, proveniente da terre e paesi lontani: Morgana e Sebile, Ponzio Pilato, la Sibilla Cumana e il Purgatorio di San Patrizio.

Con la presente, conclusiva ricerca, abbiamo investigato, infine, il cuore più interno, e originario, delle leggende che abitano i Monti Sibillini, ora finalmente liberate da tutti gli strati leggendari addizionali che sono venuti a depositarsi in questo territorio, sotto la spinta attrattiva di un potentissimo motore mitico.

E questo motore, il sogno leggendario posto alle fondamenta di tutto questo, è il terremoto (Fig. 2).

Abbiamo ipotizzato come gli abitatori preromani dei Monti Sibillini provassero timore nei confronti dei terremoti così come ne abbiamo paura anche noi oggi. Nondimeno, gli strumenti disponibili in età antica per comprendere questo spaventoso fenomeno, che frequentemente si abbatteva su di essi con potente violenza, erano assai diversi dai nostri. La conoscenza scientifica contemporanea ci permette infatti di controllare e indirizzare le nostre paure. Al contrario, le antiche popolazioni di Sabini e Piceni potevano ricorrere solamente al mito, con la generazione di opportune narrazioni leggendarie.

Queste narrazioni risultano essere oggi, naturalmente, totalmente perdute. Possiamo però tentare di ipotizzare quale sorta di sogni possano essere stati sviluppati nei cuori e nelle menti di fronte alla terrificante, devastante potenza dei terremoti. Un possibile sogno di demoni, la cui dimora si trovava al di sotto delle montagne. La necessità di un contatto, forse, allo scopo di implorare protezione e salvezza. Il Lago e la Grotta, sinistri e inquietanti, la scelta più naturale dove stabilire questo ipotetico contatto con una regione oltremondana. Punti di accesso fisicamente identificati verso un Aldilà sotterraneo, abitato da entità sovrannaturali e demoniache. Due 'hot spot' situati tra vette precipiti. Punti di riferimento geografico per la leggenda.

È questa, secondo la nostra opinione, l'impressionante ricchezza, lo straordinario spessore del contesto leggendario che segna questa bellissima, affascinante, assolutamente peculiare terra dell'Italia centrale: i Monti Sibillini. Una copiosa abbondanza di miti che è raramente rinvenibile in altre regioni del mondo.

Come osservazione finale, vogliamo evidenziare il fatto che, tra i vari punti di riferimento geografico che indicano la presenza di passaggi oltremondani, a noi tramandati dalle antiche tradizioni leggendarie, i Monti Sibillini costituiscono certamente quelli meno segnati dal carattere dell'infondatezza, della pura favola; risultando anzi questa tradizione particolarmente giustificata e quasi condivisibile, per quanto si stia trattando comunque di narrazioni mitiche.

Perché, se l'Ade nascosto nelle caverne di Cuma è meramente connesso alla natura vulcanica del luogo e ai gas venefici che riempivano quelle cavità, e il Purgatorio di San Patrizio non era altro che una sorta di sotterraneo per ingenui, opportunamente debilitati prima dell'effettuazione della loro visita e poi rinchiusi in uno spazio ristrettissimo e privo di ossigenazione, i Monti Sibillini erano un luogo dove, effettivamente, era il terrore a regnare, e una demoniaca presenza pareva manifestarsi tangibilmente attraverso gli anni e i secoli: un vero Aldilà di terremoti.

È proprio in questo contesto che il vero significato dell'antico nome dei Monti Sibillini, così come riferito da Virgilio nell'"Eneide", potrebbe rivelarsi in modo compiuto alla nostra comprensione di contemporanei: «Tetricae horrentis rupes», scrive il grande autore latino, «spaventosa, cupa, tenebrosa montagna», una terra di sinistro mistero. E terrore.

Eppure, nel corso dei secoli i popoli hanno potuto conoscere solamente la fama del Lago d'Averno a Cuma e di Lough Derg in Irlanda. È giunto dunque oggi il tempo di riconoscere ai Monti Sibillini la considerazione che essi meritano, in ragione della straordinaria qualità e della sottesa oggettività della loro leggenda.

Naturalmente, lo scenario congetturale che abbiamo presentato in questo articolo dovrà essere oggetto di ulteriori conferme.

Non sappiamo se eventuali futuri scavi effettuati al Lago e alla Grotta saranno in grado di accertare la presenza di possibili tracce riconducibili agli ipotetici santuari d'altura da noi immaginati, in forma di offerte votive, o anche resti d'ossa, depositati nei due siti nel corso dei secoli dell'Età del Ferro. Certamente, se simili resti dovessero effettivamente esistere, essi si troverebbero oggi sepolti sotto molti metri di detriti e pietrame sul fondo del Lago, o anche sotto spessi strati di roccia collassata all'interno della Grotta, oppure in pozzi del tutto irraggiungibili in fondo alla stessa caverna. Eppure, non possiamo trattenerci dal sottoscrivere pienamente quanto ipotizzato da Pio Rajna, il filologo italiano, nel 1912, in merito alla linea di ricerca da perseguire (Fig. 3):

«Si dica dopo tutto ciò se sia congettura avventata il pensiero che la caverna della Sibilla sia stata un luogo di culto ben prima che Roma distendesse su quella regione il suo dominio [...] Se la congettura coglie nel segno, scavi non superficiali avrebbero presumibilmente da condurre alla scoperta di oggetti votivi».

Ma la maggiore e più signiifcativa porzione delle future ricerche sui Monti Sibillini dovrà poggiare, nella nostra opinione, su ulteriori investigazioni storiche e archeologiche relativamente alla cultura e alle credenze dei Sabini e dei Piceni, nella constatazione che risultano essere indispensabili nuove e più approfondite indagini da effettuarsi presso numerosi siti sparsi tra i Monti Sibillini e nelle aree circostanti.

E così, il nostro lungo viaggio attraverso le affascinanti leggende che vivono nel cuore stesso dell'Italia, immerse nei fantastici scenari dei Monti Sibillini, si approssima finalmente alla conclusione.

Come in una sorta di processo di 'reverse engineering', abbiamo potuto dipanare lo spinoso intreccio costituito dalle differenti leggende che compongono il complesso sistema leggendario che abita tra le vette dell'Appennino centrale, in Italia. Per raggiungere questo obiettivo, così sfidante e stimolante, abbiamo ripercorso a ritroso i molti fili leggendari, profondamente intrecciati, che i secoli hanno intessuto su queste incredibili montagne.

Siamo fieri di avere potuto essere parte di una lunga e illustre catena di studiosi che, nel corso di ben centocinquanta anni, si sono confrontati con l'enigmatica questione posta dai racconti leggendari della Sibilla Appenninica e del Lago di Pilato, in cerca di una verità assai ammaliante ma anche particolarmente elusiva. Abbiamo avuto la possibilità di condividere gli stessi sogni che altri grandi accademici, filologi e letterati hanno voluto nutrire nei propri cuori: da Alfred von Reumont ad Arturo Graf, da Gaston Paris a Pio Rajna, da Lucy Ann Paton a Ferdinando Neri, e poi Roger S. Loomis, Fernand Desonay, Domenico Falzetti, e Luigi Paolucci, una mente particolarmente brillante che si dimostrò così acuta da sapere indicare, con sicurezza e decisione, la giusta direzione che la ricerca avrebbe dovuto seguire per risolvere questo leggendario rompicapo.

Essi furono tutti affascinati dall'incantesimo che aleggia attorno agli elevati picchi dei Monti Sibillini. Molti di loro hanno ospitato, nel proprio animo, un sogno lungo una vita: essi volevano trovare una soluzione all'enigma. E, però, essi non possedevano la giusta chiave, quella chiave così unica e particolare da permettere di disserrare la porta che conduce al nucleo più interno del mistero. Una comprensione più profonda, che può essere conquistata solamente da coloro che, anche per esperienza diretta, sappiano cosa sia un terremoto.

E siamo sicuri che, se avessimo oggi la possibilità di parlare loro, i loro occhi brillerebbero di affascinato stupore, ascoltando il racconto di una congettura che fornisce risposte esaurienti a molte delle domande che essi stessi si sono posti in relazione alle leggende dei Monti Sibillini. Perché abbiamo potuto fornire una risposta, plausibile e motivata, alla domanda più fondamentale di tutte, l'interrogativo che un filologo, Paolo Toschi, e il suo brillante allievo, Luigi Paolucci, vollero esprimere molti decenni fa:

«Ma perché proprio in questi determinati luoghi e non in altri abitava la Sibilla, e i maghi vengono a consacrare il libro del Comando?»

È esattamente questa la domanda che ci eravamo posti anche noi nel corso della nostra ricerca, esplicitandola nei nostri precedenti articoli "Nascita di una Sibilla: la traccia medievale" e "Una leggenda per un prefetto romano: i Laghi di Ponzio Pilato": quale sorta di magnetica attrazione ha potuto attirare una varietà così significativa di magiche, estranee narrazioni leggendarie fino alle vette del Monte Vettore e del Monte Sibilla? Per quale strano destino una Sibilla Appenninica e un prefetto romano, accompagnati da sinistri racconti concernenti devastanti tempeste, sono venuti a riposare, come la sfera metallica vorticante sul disco di una roulette, proprio nella posizione marcata da queste remote montagne d'Italia?

A quel tempo, avevamo già iniziato a ritenere che una tale forza attrattiva dovesse trovare origine in qualche particolare condensazione relativa, in modo specifico, alla natura di questi luoghi, i Monti Sibillini; un effetto prodotto da qualche sconosciuto fattore locale, un risultato delle peculiarità fisiche di questo meraviglioso territorio: peculiarità che lo rendevano capace di generare una potente attrazione mitica nei confronti di narrazioni leggendarie altamente emozionali.

E la specifica peculiarità di questa terra, i Monti Sibillini, è costituita dai terremoti.

I terremoti: «il più terribile dei fenomeni che sottoponga a' nostri sguardi il pianeta da noi abitato», come ebbe a scrivere Leopoldo Mannocchi nel 1859, «il paurosissimo flagello del tremuoto, che assai volte avea costernata e concussa questa città» (Fig. 4).

Un evento terrificante, così maligno da dare origine a descrizioni spaventose come quella che troviamo nelle cronache che narrano del devastante terremoto che ebbe luogo nell'anno 1703 (Fig. 5):

«Ad un'ora, e quasi tre quarti di notte del detto giorno venne un così fiero e terribile Terremoto, seguitato da molti altri di non minore spavento in tutto lo spazio di quella funestissima notte, ed accompagnato da' tuoni, da' lampi, da fetori bituminosi, e da così continovi tremori della terra, che oltre l'intero eccidio di Norcia, sembrava che assorbir volesse quanto le stava di sopra, or'alzandosi, or'abbassandosi quasi tutte le fabbriche, e quando agitavansi da una banda, e quando dall'altra; al che si aggiugnevano lo strepitoso fragore delle mura, che rovesciavano, strida spaventose, clamori terribili, e voci sotterranee».

Vita e morte, esistenza terrena e potenze sovrannaturali, uomini travolti dal timore e demoniache divinità: le speranze e le paure più profonde albergate nel cuore dell'umanità hanno trovato una dimora particolarmente confacente in questa piccola porzione d'Italia e d'Europa.

E dunque, il nostro lavoro è completato. Spetta ora a studiosi e ricercatori proseguire lungo il sentiero che abbiamo tracciato, oppure rigettarlo.

Vogliamo però aggiungere, solamente, un'ultima considerazione conclusiva.

Forse, il modello che abbiamo delineato, coinvolgente terremoti e leggendari demoni ad essi preposti, potrebbe suonare come assurdo, e anche in qualche modo avventato, se non del tutto delirante.

A questo genere di critica, non intendiamo replicare riproponendo, nuovamente, le numerose considerazioni da noi già illustrate nel corso della presente ricerca.

Intendiamo invece fornire una diversa risposta, assai più efficace.

Perché, nell'anno 2016, come già sappiamo, molti potenti terremoti hanno colpito i Monti Sibillini.

E il giorno 28 novembre 2019, tre anni dopo, l'agenzia giornalistica ANSA ha diffuso una serie di interviste raccolte da un corrispondente locale, Gianluigi Basilietti, presso Castelluccio di Norcia, il piccolo borgo posto al centro di questo territorio, un insediamento che è stato completamente demolito dalle terrificanti onde sismiche (Fig. 6).

È stato intervistato un uomo. Un uomo anziano, nato a Castelluccio, il quale, benché oggi residente in Roma, ha abitato per gran parte della propria vita di fronte ai ripidi versanti del Monte Vettore. Si tratta di un uomo dei nostri tempi, e dunque ciò che egli ha voluto dichiarare non può che costituire una debole ombra di quei sentimenti che gli antichi abitanti dei Monti Sibillini possono avere esperimentato nel proprio animo in una remota antichità, quando i terremoti colpivano, con la massima potenza, le loro dimore e la loro terra.

Eppure, le sue parole, benché pronunciate da una voce contemporanea, sono state del tutto significative:

«... poi arriva il Diavolo sotto, e sfascia tutto».

Un Demone giunge, dal sottosuolo. E devasta la terra intera.

L'Età del Ferro, tra i Monti Sibillini, pare improvvisamente raggiungere la nostra era scavalcando l'insondabile abisso del tempo: sulle inquietanti, divine, terrificanti onde del terremoto.

18 Apr 2020

Sibillini Mountain Range, the chthonian legend /7. A new interpretation of the meaning of the mythical tale

In the present paper, we have presented a new hypothesis on the potential origin of the legendary tales which are found amid the Sibillini Mountain Range. We conjectured that, during the Iron Age, the local populations of Sabines and Picenes, recurrently struck by devastating earthquakes and ceaselessly exposed to the ominous tremors of the earth, may have established highland shrines at the Lake set on Mount Vettore and the Cave situated on the cliff of Mount Sibyl, which later legendary layers will trasform into a Sibyl's Cave and a Lake of Pilate.

The terrifying cohabitation with the seismic shakings may have fostered the production of legendary credences that were possibly related to demonic beings who lived beneath the Sibillini Mountain Range: fiendish demons who presided over the earthquakes, and could be queried for mercy at two specific, emotionally-potent sites: the Lake and the Cave, both placed at eerie, uncanny settings. Two landmarks, two geographical features marking an entryway to a superhuman Otherworld.

Not a Sibyl, nor a Roman prefect. Instead, a personification of earthquakes: a most powerful and devastating might, typically smashing this Apennine land since time immemorial.

Earthquakes as an otherwordly power, deserving worship in search of protection and salvation.

We want to stress the fact that our conjecture, of which we have seen in the present paper a series of supporting considerations, is not foreign to the ancient cultures of Italy, both pre-Roman and Roman.

In our previous paper “Sibillini Mountain Range, a cave and lake to the Otherworld”, we already mentioned a most impressive passage taken from Book VI of the “Aeneid” by Publius Vergilius Maro, written in the first century B.C. When the Cumaean Sibyl, by art of necromancy, opens wide the gate of the frighful cave which is the entryway to Hades, by raising an appeal to Hecate, something absolutely appalling occurs.

It is earthquake:

«See now, at the dawn light of the rising sun,

the ground bellowed under their feet, the wooded hills began

to move, and, at the coming of the Goddess, dogs seemed to howl

in the shadows».

[In the original Latin text (lines 255-258):

«Ecce autem, primi sub lumina solis et ortus,

sub pedibus mugire solum, et iuga coepta moveri

silvarum, visaeque canes ululare per umbram,

adventante dea»].

The bellow of the ground at Cumae. The yell of the ravaged cliffs amid the the Sibillini Mountain Range. The mythical power of earthquakes travels far and wide across different populations and ages. But the terror experienced by human beings remains the same. And necromancy seems to be considered powerful enough to exert some kind of control over the chthonian powers, as shown by Vergil's text with poetical mastery.

Because the Romans, too, were in awe of earthquakes, despite all their efforts at finding prescientific explanations to this baleful phenomenon, as in the works written by Lucretius, Seneca and Pliny.

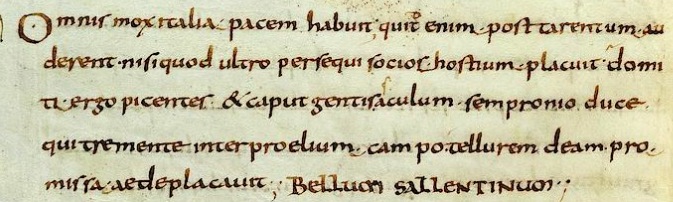

When the Roman troops swept the land of the Picenes in the year 268 B.C., and a fierce battle was being fought near Asculum, today's town of Ascoli, set on the eastern edge of the Sibillini Mountain Range, a visitors came uninvited amid the slaughter.

Again, it was earthquake.

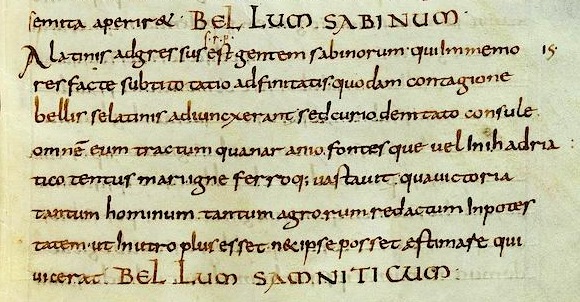

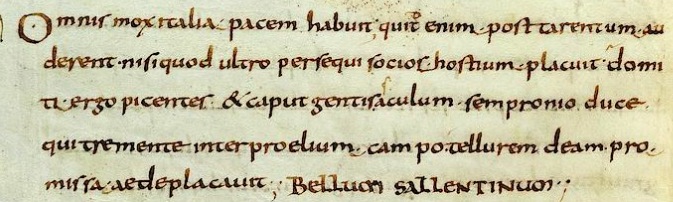

And second-century Latin writer Lucius Annaeus Florus, in his “Epitomae de Tito Livio”, reports to us all the surprise and fear experienced, during the terrifying event, by the Roman commander, consul Publius Sempronius Sophus (Fig. 1):

«The people of Picenum were therefore subdued and their capital Asculum was taken under the leadership of Sempronius, who, when an earthquake occurred in the midst of the battle, appeased the goddess Tellus by the promise of a temple».

[In the original Latin text: «Domiti ergo picentes et caput gentis asculum sempronio duce, qui tremente inter proelium campo tellurem deam promissa aede placavit»].

While the appalling earthquake was visiting again the region of the Sibillini Mountain Range, certainly nobody stopped to consider pensively the remarkable winds that, according to the lesson of Aristotle, were seemingly pushing the ground from below: instead, in utter terror, they hastened to implore goddess Tellus, the Roman deity of the earth, for salvation and mercy. And, afterwards, they gratefully built a temple dedicated to the deity in downtown Rome.

When experienced personally, one senses with all one's body that earthquakes are a supernatural affair.

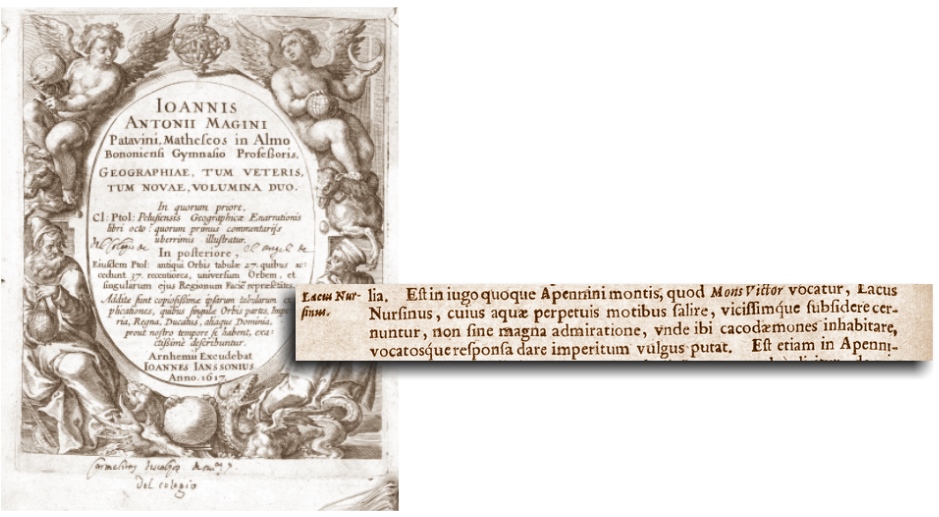

So no Apennine Sibyl has ever existed on the peaks of the Sibillini Mountain Range. Disguised by many extraneous legendary layers added to her semblance, her true features seem to faintly reemerge from the reference provided by Martino Delrio, a sixteenth-century Flemish author from which we already quoted in our previous article “Apennine Sibyl: the bright side and the dark side”. In his “Disquisitionum magicarum libri sex”, published in 1599, he places the Sibyl of Norcia within the ranks of subterranean demons, defined by Johannes Trithemius sixty years earlier.

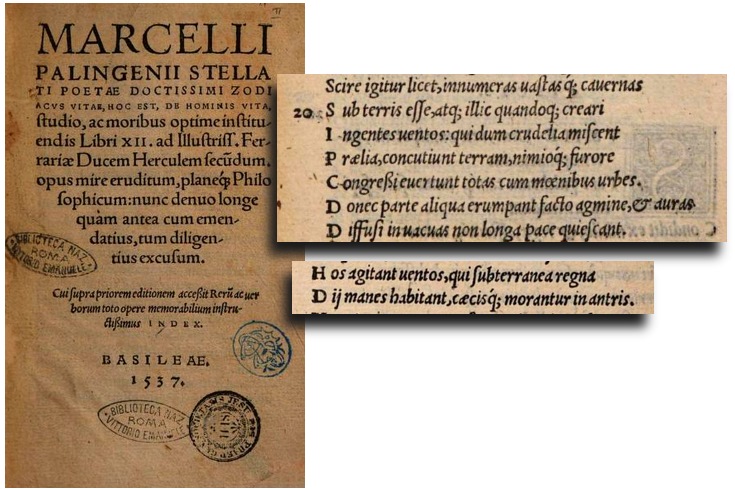

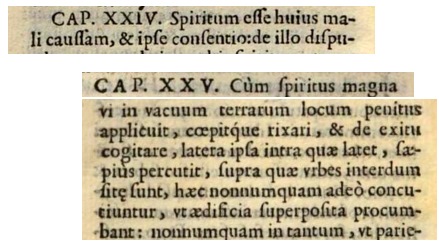

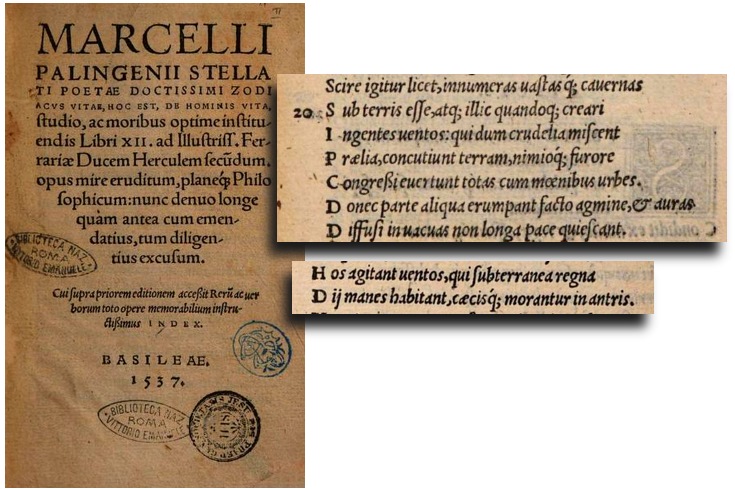

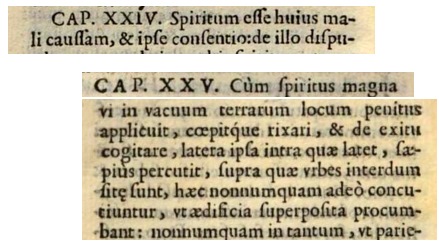

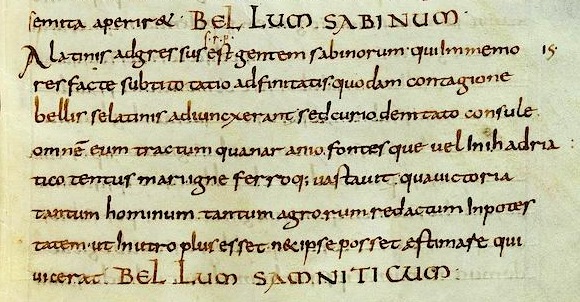

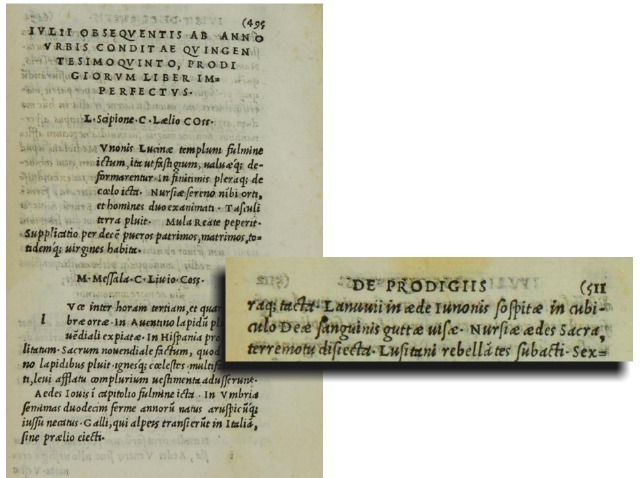

But Trithemius, in his “Liber octo questionum ad Maximilianum Cesarem”, had written the following words (Quaestio Sexta) (Fig. 2):

«The fifth kind [of demons] is called subterranean: they are the ones who reside in caverns and caves and hollows placed under remote peaks. The power of such demons is utterly evil [...]. They are most willing to harm human beings. They can cause wind and flames to erupt from holes in the ground. And they can shake the foundations of buildings».

[In the original Latin text: «Quintum genus subterraneum dicitur: quod in speluncis et cavernis montiumque remotis concavitatibus demorant. Et isti daemones affectione sunt pessimi. [...] In pernicie humani generis paratissimi. Hiatus efficiunt terrae, ventosque flamiuomos suscitant & fundamenta edificiorum concutiunt».]

They harm mankind. They open cracks in the earth. They raise fiery wind. They shake the foundations of buildings.

This is earthquake.

And the Apennine Sibyl, through a mediation which has lasted for millennia, from the Iron Age to Delrio and Trithemius, by this excerpt appears to have come back to her first nature and origin.

Monti Sibillini, la leggenda ctonia /7. Una nuova interpretazione del significato del racconto leggendario

Nella presente ricerca, abbiamo illustrato una nuova congettura relativa alla potenziale origine dei racconti leggendari che sono rinvenibili tra i Monti Sibillini. Abbiamo ipotizzato come, nel corso dell'Età del Ferro, le popolazioni locali di Sabini e Piceni, ricorsivamente colpite da devastanti terremoti e continuativamente esposte ai minacciosi tremori della terra, possano avere stabilito dei santuari d'altura presso il Lago situato sul Monte Vettore e alla Grotta posta sul picco del Monte Sibilla, due luoghi che più tardi livelli leggendari, sopraggiunti successivamente, avrebbero poi trasformato nella Grotta della Sibilla e nel Lago di Pilato.

La terrificante coabitazione con gli scuotimenti sismici potrebbe avere favorito la produzione di credenze leggendarie forse connesse con entità demoniache che avrebbero dimorato al di sotto dei Monti Sibillini: demoni maligni che avrebbero governato i terremoti, e ai quali sarebbe stato possibile rivolgersi per implorare salvezza presso due specifici luoghi di grande impatto emotivo: il Lago e la Grotta, ambedue collocati in scenari inquietanti e sinistri. Due elementi naturali, due punti di riferimento geografico che avrebbero marcato la presenza di ingressi a regioni oltremondane e sovrumane.

Non una Sibilla, non un prefetto romano. Invece, una personificazione dei terremoti: una potenza aggressiva e distruttiva, che ha tipicamente colpito questa porzione degli Appennini sin da tempi remoti.

I terremoti come un potere oltremondano, al quale tributare venerazione in cerca di protezione e salvezza.

Vogliamo riaffermare il fatto che la nostra congettura, in relazione alla quale abbiamo potuto proporre, nel presente articolo, una serie di considerazioni a supporto, non risulta essere estranea alle antiche culture d'Italia, sia pre-romane che romana.

Nel nostro precedente articolo "Monti Sibillini, un Lago e una Grotta come accesso oltremondano", abbiamo già avuto occasione di menzionare un passaggio estremamente significativo tratto dal Libro VI dell'"Eneide" di Publio Virgilio Marone, opera risalente al primo secolo a.C. Quando la Sibilla Cumana, per arte di negromanzia, spalanca l'ingresso della spaventosa caverna che costituisce l'ingresso all'Ade, innalzando un'invocazione a Ecate, qualcosa di assolutamente agghiacciante ha luogo.

È il terremoto:

«Ed ecco, alla soglia del primo sole e sul sorgere,

a muggir sotto i piedi la terra, le cime degli alberi a scuotersi

presero, parvero cagne ululare per l'ombra

al venir della dèa».

[Nel testo originale latino (vv. 255-258):

«Ecce autem, primi sub lumina solis et ortus,

sub pedibus mugire solum, et iuga coepta moveri

silvarum, visaeque canes ululare per umbram,

adventante dea»].

Il muggito della terra a Cuma. L'urlo delle cime percosse tra i Monti Sibillini. La potenza mitica dei terremoti percorre grandi distanze, tra popoli diversi e attraversando i secoli. Ma il terrore esperimentato dagli esseri umani rimane sempre lo stesso. E pare che la negromanzia sia considerata sufficientemente efficace per l'esercizio di una qualche forma di controllo sulle potenze ctonie, come mostrato nel testo di Virgilio, con mirabile maestria poetica.

Perché anche i romani avevano timore dei terremoti, a dispetto di tutti i loro sforzi per elaborare spiegazioni prescientifiche relativamente a questo maligno fenomeno, come nelle opere di Lucrezio, Seneca e Plinio.

Quando le truppe romane dilagarono nella terra dei Piceni nell'anno 268 a.C. e una feroce battaglia era in corso in prossimità di Asculum, l'odierna città di Ascoli, situata ai confini orientali dei Monti Sibillini, un visitatore si presentò inatteso in mezzo ai massacri.

Di nuovo, era il terremoto.

E l'autore latino Lucio Anneo Floro, vissuto nel secondo secolo, nella sua "Epitomae de Tito Livio", ci racconta tutta la sorpresa e la paura esperimentate, durante quel terrificante evento, dal comandante romano, il console Publio Sempronio Sofo (Fig. 1):

«I Piceni furono dunque soggiogati e la loro capitale, Asculum, fu presa sotto la guida di Sempronio, il quale, quando un terremoto si verificò nel corso della battaglia, placò la dea Tellus con la promessa di un tempio».

[Nel testo originale latino: «Domiti ergo picentes et caput gentis asculum sempronio duce, qui tremente inter proelium campo tellurem deam promissa aede placavit»].

Quando uno spaventoso terremoto giunse a visitare nuovamente la regione dei Monti Sibillini, di certo nessuno si fermò a considerare pensosamente quei venti così peculiari che, secondo la lezione di Aristotele, stavano verosimilmente premendo la terra dal di sotto: invece, al colmo del terrore, essi si affrettarono a invocare la dea Tellus, la divinità romana della terra, implorando protezione e salvezza. E, successivamente, costruirono, con grata riconoscenza, un tempio dedicato alla divinità, proprio nel centro di Roma.

Quando se ne fa esperienza personalmente, si comprende con tutto il proprio corpo come i terremoti costituiscano una questione sovrannaturale.

E dunque, nessuna Sibilla Appenninica è mai esistita sulle vette dei Monti Sibillini. Occultata dai molti livelli leggendari estranei che ne hanno mascherato il sembiante, i suoi veri lineamenti sembrano riemergere debolmente nel riferimento fornito da Martino Delrio, un autore fiammingo vissuto nel sedicesimo secolo dal quale abbiamo già avuto occasione di citare alcuni brani nel nostro precedente articolo "Sibilla Appenninica: il lato luminoso e il lato oscuro". Nel suo "Disquisitionum magicarum libri sex", pubblicato nel 1599, egli colloca la Sibilla di Norcia tra i ranghi dei demoni sotterranei, secondo la catalogazione definita da Giovanni Tritemio sessanta anni prima.

Ma Tritemio, nella sua opera "Liber octo questionum ad Maximilianum Cesarem", aveva scritto le seguenti parole (Quaestio Sexta) (Fig. 2):

«Il quinto genere [di demoni] è chiamato sotterraneo: coloro che dimorano nelle spelonche e caverne e cavità delle remote montagne. E questi dèmoni sono estremamente pericolosi [...]. Sono particolarmente desiderosi di nuocere al genere umano. Essi sono inoltre in grado di suscitare venti e fiamme dalle fenditure della terra. E scuotono le fondamenta degli edifici».

[Nel testo originale latino: «Quintum genus subterraneum dicitur: quod in speluncis et cavernis montiumque remotis concavitatibus demorant. Et isti daemones affectione sunt pessimi. [...] In pernicie humani generis paratissimi. Hiatus efficiunt terrae, ventosque flamiuomos suscitant & fundamenta edificiorum concutiunt»].

Essi nuocciono al genere umano. Essi aprono fessure nella terra. Essi suscitano venti di fuoco. Essi scuotono le fondamenta degli edifici.

Questo è il terremoto.

E la Sibilla Appenninica, attraverso una mediazione che è durata per millenni, dall'Età del Ferro fino a Delrio e Tritemio, con questo brano pare veramente essere tornata alla sua prima natura e origine.

17 Apr 2020

Sibillini Mountain Range, the chthonian legend /6.6 The earthquakes which arise from the subterranean winds

In the legendary tradition of the Sibillini Mountain Range, winds and tempests are not just natural winds and tempest.

As we stated in the previous paragraph, there is more to it.

A first hint to the special character of winds in this magical context is provided to us by that same Pierre Crespet from whom we quoted passages about the Sibyl's Cave, drawing from his “De la hayne de Satan et malins esprist contro l'homme”, published in 1590.

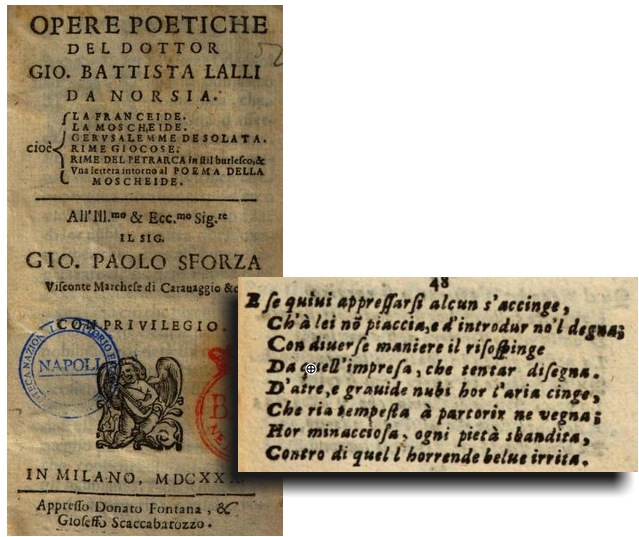

As we already noted in our previous article “Sibillini Mountain Range: the legend before the legends”, Crespetus adds an additional reference to the magical, divine quality of such tempests and winds (Livre I, Discours 6) (Fig. 1):

«Heavenly Gods or maybe the stars themselves send those winds

Often it happens that when a Wizard wants to find treasures hidden beneath the ground

or consecrate his spellbook

or by a sorcerous ritual subjugate some god to his will,

I heard that winds raise, and sudden storms».

[In the original Latin text:

«Hos ventos vel Dij aerij vel sydera mittunt,

Sepae etenim cum thesauros tellure latentes,

Vult auferre Magus vel consecrare libellum,

Vel magico ritu quemquam sibi subdere divum,

Audivi exortum ventum, subitamque procellam»].

This suggestion, which Crespetus draws from a sixteenth-century work, the “Zodiacus Vitae”, written by Marcellus Palingenius Stellatus in 1536, confirms a potential interpretation of the storms and ensuing devastations as something different from a mere weather disturbance, though severe as it may be.

And such winds are not related only to necromantic arts, for Palingenius, in his poem, adds the following words (Liber XI, “Aquarius”) (Fig. 2):

«Know then that innumerable, immense caverns

lay beneath the earth; and when there fierce winds

are generated, then they rouse savage

battles, smite the earth, and with extraordinary fury

they gather and overturn every town with their ramparts,

until at some spot they erupt as a multitude, and

disperse themeselves in the air as blows of wind

which finally vanish in peace [...]

So are the troubled winds, which inhabit the subterranean abodes

of the shades of the dead, who dwell in the darkness of caves».

[In the original Latin text:

«Scire igitur licet, innumeras vastasque cavernas

Sub terris esse, atque illic quandoque creari

Ingentes ventos; qui dum crudelia miscent

Proelia, concutiunt terram, nimioque furore

Congressi evertunt totas cum moenibus urbes.

Donec parte aliqua erumpant facto agmine, et auras

diffusi in vacuas non longa pace quiescant. [...]

Hos agitant ventos, qui subterranea regna

Dij manes habitant, caecisque morantur in antris.»].

Because winds are mythically linked to earthquakes.

The connection between storms and seismic waves is not a concept developed in the sixteenth century by Palingenius. Actually, it represents a most antique, prescientific explanation on the origin of earthquakes.

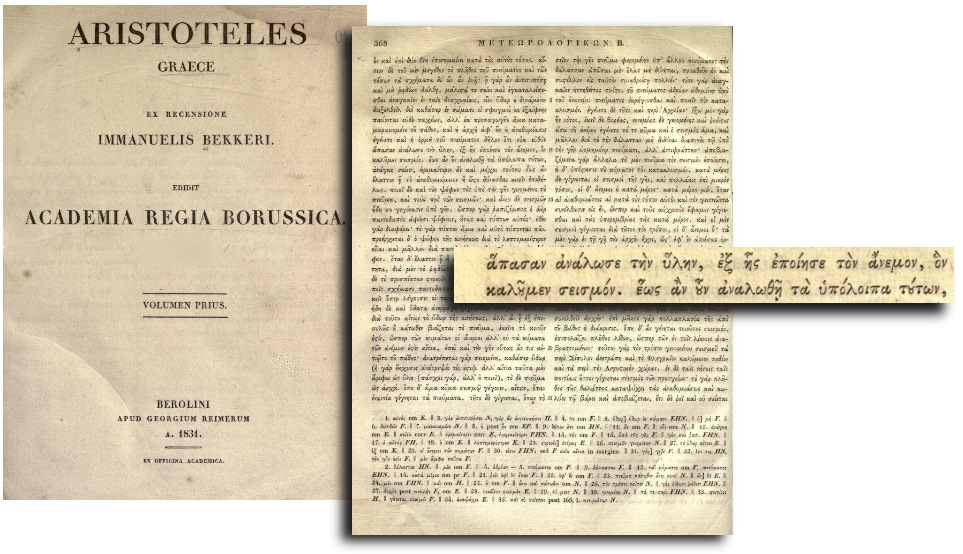

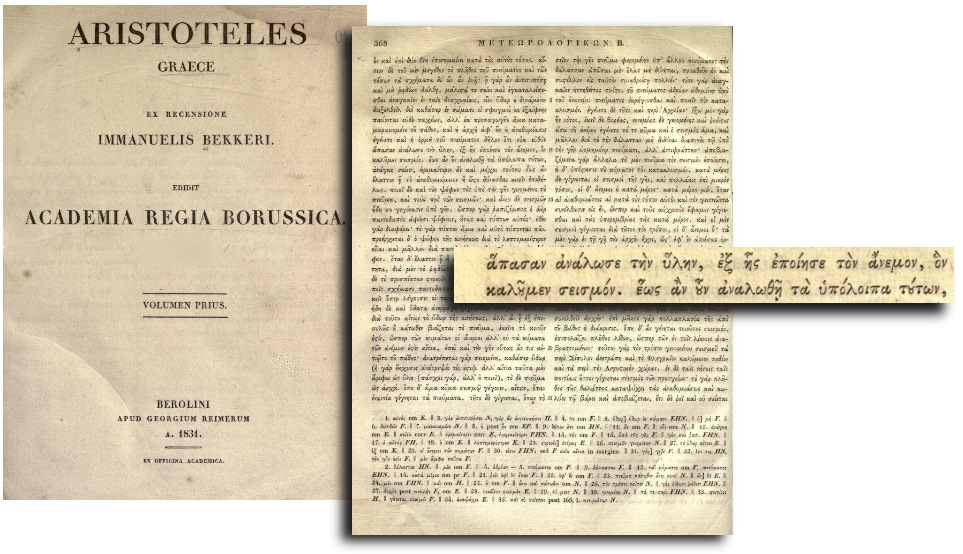

It is around the year 340 B.C. that Aristotle, the great philosopher of ancient Greece, elaborates his comprehensive treatise “Meteorologica”, the first written essay on the parts of the earth and the universe, the elements of which the world is composed, and the origin of natural events, including earthquakes.

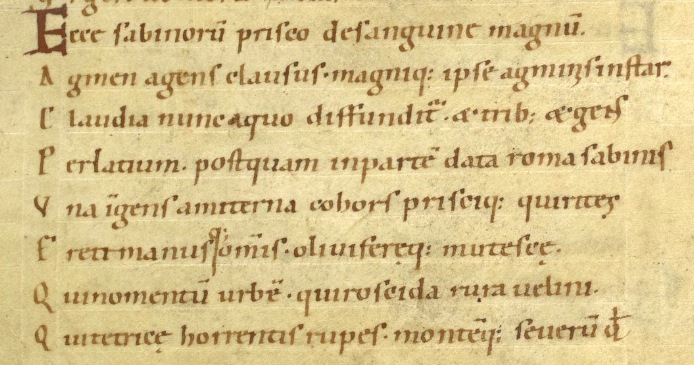

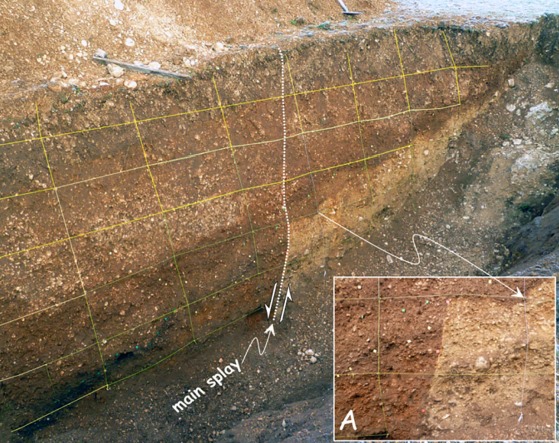

According to Aristotle (“Meteorologica”, Book II, Part VIII), the shaking of the earth is caused by «the wind which we call an earthquake. [...] When the wind is present in sufficient quantity there is an earthquake». For the Greek philosopher, «the earth is spongy and cavernous», so that «the severity of the earthquake is determined by the quantity of wind and the shape of the passages through which it flows. Where it is beaten back and cannot easily find its way out the shocks are most violent, and there it must remain in a cramped space like water that cannot escape». Because when «a great wind is compressed into a smaller space and so gets the upper direction, [...] then breaks out and beats against the earth and shakes it violently» (Fig. 3).

Earthquakes and winds. Winds which circulate beneath the ground, across huge, unseen hollows that pierce the earth underneath. And when the pressure of the winds becomes unbearable, the earth is shaken and beaten and struck. It is an earthquake.

Furthermore, when the underground winds erupt, a devastating storm occurs:

«The countries that are spongy below the surface are exposed to earthquakes because they have room for so much wind. [...] It has been known to happen that an earthquake has continued until the wind that caused it burst through the earth into the air and appeared visibly like a hurricane» (Fig. 4).

Earthquakes and winds, then turning into storms. Such is the intimate connection which, in antiquity, was believed to exist between seismic events, devastation of the land, and tempests. A connection that will mark the legendary tale of the Sibillini Mountain Range for its whole history.

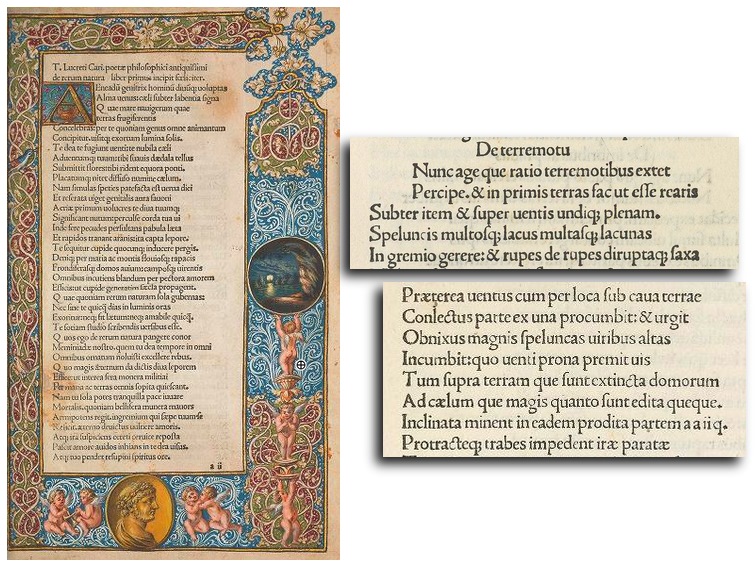

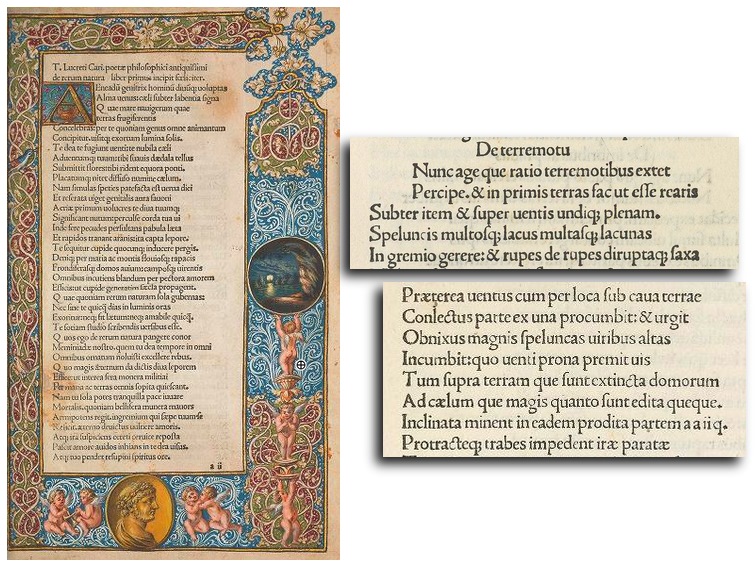

Aristotle's model will be adopted and extended by Titus Lucretius Carus, the great Roman philosopher and poet, who lived in the first century B.C. In his poem “De rerum natura” (“On the nature of things”), he describes with poetical, fascinating words the hollows which lie beneath the surface of the earth (Book VI, vv. 535-539 and 557-564) (Fig. 5):

«Now come the Earthquake's causes learn: and first

Conceive the Earth as on its surface seen,

So constituted is in depths below;

Hence, in its bosom holds vast windy caves,

Innumerable lakes, chasms, and pools profound,

With rocks abrupt, and cliffs precipitous [...]

When winds pent up in hollow depths

Bear to one part with shouldering violence,

They forceful heave the cavern's domed roof,

Till Earth gives way where the prone winds impend.

Then lofty buildings on the surface reared,

The more toward heaven they lift aspiring heads,

The more, bulging and forced awry they yield,

And started beams impend prepared to fall».

[In the original Latin text:

«Nunc age, que ratio terremotibus extet

Percipe. et in primis terram fac ut esse rearis

Subter item ut super ventis undique plenam.

Speluncis multosque lacus multasque lacunas

In gremio gerere et rupes diruptaque saxa; [...]

Praeterea ventus cum per loca sub cava terrae

Conlectus parte ex una procumbit et urgit

Obnixus magnis speluncas viribus altas,

Incumbit quo venti prona premit vis.

Tum supra terram que sunt extincta domorum

Ad caelum que magis quanto sunt edita queque.

Inclinata minent in eadem prodita partem

Protractaeque trabes impendent irae paratae»].

With great dramatic force, Lucretius depicts the terrifying effects of earthquakes, as generated by the subterranean winds, on the artifacts on men (vv. 570-576) (Fig. 6):

«Now because those winds

Blow back and forth in alternation strong,

And, so to say, rallying charge again,

And then repulsed retreat, on this account

Earth oftener threatens than she brings to pass

Collapses dire. For to one side she leans,

Then back she sways; and after tottering

Forward, recovers then her seats of poise.

Thus, this is why whole houses rock, the roofs

More than the middle stories, middle more

Than lowest, and the lowest least of all».

[In the original Latin text:

«Nunc quia respirant alternis inque gravescunt

Et quasi conlecti redeunt ceduntque repulsi,

Saepius hanc obrem minutatur terra ruinatur.

Quam facit; inclitus enim retroque recellat

Et recipit pro lapsa suas in pondere sedes.

Hac igitur rartione vacillant omnia tecta,

Summa magis mediis, media imis, ima per hilum»].

Again, the earthquakes are mighty commotions of the earth produced by the circulation of winds underneath, in the ghastly caverns concealed beneath the feet of men, and that no men has ever seen.

But earthquakes can become even more destructive when the winds find their way out of the earth, and plague the world above (vv. 577-584 and 591-600) (Fig. 7):

«Another cause of fearful tremblings is

When some tornado coming from without,

Or sprung in some dark subterranean mine,

Rushes to hollow places of the earth

And with wild tumult raves her caves among;

Till forceful whirling, bursting forth at length

In hideous yawnings, rends the founded Earth. [...]

Even when such prisoned winds fail to burst forth,

They rush through veins of Earth, and tremblings come,

As shudderings oft over shivering members creep.

How then do smitten populations quake

With terrors overhead, terrors beneath

Their feet, lest caverns crumbled up should open

Sudden wide jaws, ingulfing ruins round».

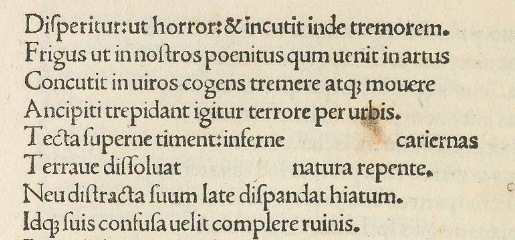

[In the original Latin text:

«Est haec eiusdem quoque magni causa tremoris.

ventus ubi atque animae subito vis maxima quedam

aut extrinsecus aut ipsa tellure coorta

in loca se cava terra coniecit ibique

speluncas inter magnas fremit ante tumulto

vesabundaque portatur post incita cum vis

exagitata foras erumpitur et simul altam

diffidens terram magnum concinnat hiatum. [...]

Quod nisi prorumpit tamen impetus ipse animai

et fera vis venti per crebra foramina terrae

disperitur ut horror et incutit inde tremorem.

frigus ut in nostros poenitus qum venit in artus

concutit in viros cogens tremere atque movere.

ancipiti trepidant igitur terrore per urbis.

tecta superne timent, inferne [metuunt] cavernas

terra ne dissolvat natura repente,

neu distracta suum late dispandat hiatum

idque suis confusa velit complere ruinis».

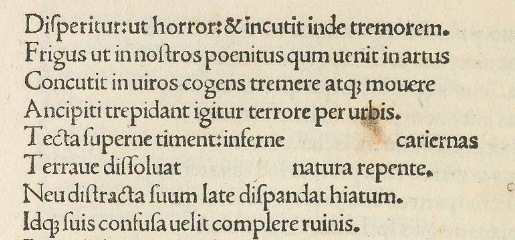

In the year 63 A.D., it is Lucius Annaeus Seneca, the illustrious philosopher who was tutor to Emperor Nero, who further develops the antique theoretical framework on the origin of seismic events. In his “Naturales quaestiones” he dedicates a full, extensive chapter to earthquakes.

After proposing a detailed summary of the opinions held by his Greek and Latin predecessors, Seneca illustrates his own view of the reason for which earthquakes are unleashed (Book VI, Chapter XVIII) (Fig. 8):

«The chief cause of earthquake, therefore, is air, an element naturally swift and shifting from place to place. As long as it is not stirred, but lurks in a vacant space, it reposes innocently, giving no trouble to objects round it. But when any cause coming upon it from without rouses it, or compresses it, and drives it into a narrow space, in the first instance, to be sure, it merely retires and roams about its enclosure. But when opportunity of escape is cut off, and resistance meets it on all hands, then 'with deep murmur of the mountain - It roars around the barriers' [a verse from vergil's "Aeneid", editor's note] which, after long battering, it dislodges and tosses on high, growing the more fierce, the stronger the obstacle with which it has contended. By and by, when it has traversed the whole space in which it was enclosed, and has failed to find a way of escape, it recoils from the side on which its impact was greatest. It is then either distributed through the secret openings which the earthquake of itself causes here and there, or escapes through a new rent. So uncontrollable is this mighty power. No bolt can imprison wind».

[In the original Latin text: «Maxima ergo causa est, propter quam terra moveatur, spiritus natura citus, et locum e loco mutans. Hic quamdiu impellitur, et in vacanti spatio latet, iacet innoxius, nec circumiectis molestus est. Ubi illum extrinsecus superveniens caussa solicitat compellitque et in arctum agit, scilicet adhuc, cedit tantum et vagatur. Ubi erepta discedendi facultas est, et undique obsistitur, tunc 'magno cum murmure montis Circum claustra fremit', quae diu pulsata convellit ac iactat; eo acrior quo cum ualentiore mora luctatus est. Deinde cum circa perlustravit omne quo tenebatur, nec potuit euadere, inde, quo maxime impactus est, resilit; et aut per occulta dividitur, ipso terraemotu raritate facta, aut per novum vulnus emicuit. Ita eius vis tanta non potest cohiberi, nec ventum tenet ulla compages»].

So, in the opinion expressed by Seneca, earthquakes and winds are closely connected (Book VI, Chapter XXIV and XXV) (Fig. 9):

«I shall be ready to allow that air is the cause of this calamity. [...] When air has completely filled a large vacant space within the earth, and has begun to struggle and meditate escape, it lashes again and again the sides of the enclosure within which it lurks, and right over which, as it happens, cities are sometimes situated. The shaking is at times so violent that buildings standing above the area of disturbance are thrown down».

[In the original Latin text: «Spiritum esse huius mali caussam et ipse consentio. [...] Cum spiritus magna vi in vacuum terrarum locum penitus applicuit, coepitque rixari, et de exitu cogitare, latera ipsa íntra quae latet, saepius percutit, supra quae urbes interdum site sunt, haec nonnumquam adeo concutiuntur, ut aedificia superposita procumbant»].

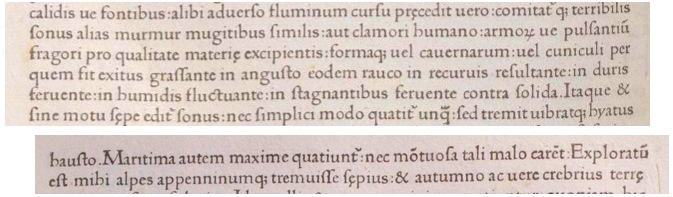

In the second half of the first century, Pliny the Elder, the philosopher and navy commander who died on the shore of Herculaneum during the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius, adhered to the conjecture that Aristotle, Lucretius and Seneca had endorsed (“Naturalis historia”, Book II, Chapter LXXXI) (Fig. 10):

«I certainly conceive the winds to be the cause of earthquakes. [...] For the trembling of the earth resembles thunder in the clouds; nor does the yawning of the earth differs from the bursting of the lightning; the enclosed air struggling and striving to escape».

[In the original Latin text: «Ventos in causa esse non dubium reor. [...] neque aliud est in terra tremor quam in nube tonitruum. Nec hyatus aliud quam cum fulmen erumpit incluso spiritu luctante et ad libertatem exire nitente»].

From his words, it really seems that Pliny may have had a direct experience of the occurrences associated to seismic events, even though he surely conducted his own investigations (Book II, Chapter LXXXII) (Fig. 11):

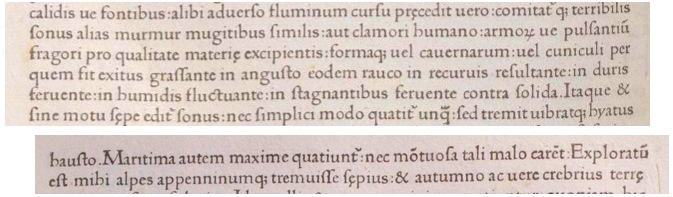

«A terrible noise precedes and accompanies the shock; sometimes a murmuring, like the lowing of cattle, or like human voices, or the clashing of arms. This depends on the substance which receives the sound, and the shape of the caverns or crevices through which it issues; it being more shrill from a narrow opening, more hoarse from one that is curved, producing a loud reverberation from hard bodies, a sound like a boiling fluid from moist substances, fluctuating in stagnant water, and roaring when forced against solid bodies. There is, therefore, often the sound without any motion. Nor is it a simple motion, but one that is tremulous and vibratory. [...] I have found, by my inquiries, that the Alps and the Apennines are frequently shaken».

[In the original Latin text: «Praecedit vero comitaturque terribilis sonus, alias murmur mugitibus similis, aut clamori humano armorumve pulsantium fragori, pro qualitate materiae excipientis formaque vel cavernarum vel cuniculi per quem fit, exitus grassante in angusto eodem rauco in recurvis resultante in duris, fervente in umidis fluctuante in stagnantibus feruente contra solida. Itaque et sine motu saepe editur sonus; nec simplici modo quatitur unquam, sed tremit vibratque. [...] Exploratum est mihi alpes appenninumque tremuisse saepius»].

But wind is the cause, and when the pressure of winds lessens, the earthquake is over (Book II, Chapter LXXXIV) (Fig. 12):

«The tremors cease when the vapour bursts out; but if they do not soon cease, they continue for forty days; generally, indeed, for a longer time: some have lasted even for one or two years».

[In the original Latin text: «Desinunt autem tremores cum ventus emergit; sin vero duraverint non ante XL dies sistuntur plerumque et tardius, utpote cum quidam annuo et biennii spacio duraverint»].

Thus, throughout classical antiquity scholars have tried to explain the reason for the occurrence of earthquakes by adopting a prescientific model, based on winds circulating in the hidden hollows of the earth. Sometimes, winds exert a mighty pressure on their subterranean abodes, and their oscillating motion generates seismic effects on the surface; sometimes, they even succeed in escaping their underground prisons, so giving way to powerful storms which contribute to the overall destruction of the land above.

While the men of the Iron Age who lived amid the Apennines had confronted with the frightful seismic waves which recurrently struck their territory by possibly imagining a dream of demonic gods lurking beneath their mountains, the Greeks and Romans followed an utterly different path, impervious as it was in the lack of any solid scientific foundations, and yet based on fully natural, worldly considerations, with no need to introduce any god or demon: a path that will eventually lead the culture of the Western world to modern science as we know it today.

However, for the time being winds and tempest were the only available explanation to earthquakes. The advent of the Christian age will add substantially nothing to this conceptual framework, and the wind theory will remain undisputed until the Renaissance, as we noted in the Zodiacus Vitae, written by Marcellus Palingenius Stellatus in 1536.

And it is not by a mere chance that subterranean winds are also explicitly mentioned by the key authors of the sibilline legendary tradition, Andrea da Barberino and Antoine de la Sale:

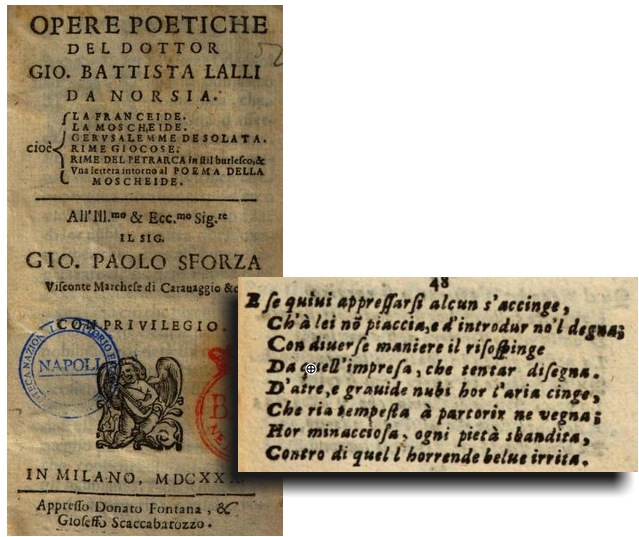

In his Guerrino the Wretch, Andrea da Barberino sends his knight hero into the Purgatory of St. Patrick, immediately after his forbidden visit to the Apennine Sibyl. There, Guerrino is surrounded by angered demons, who break in accompanied by a fiendish wind, which Andrea da Barberino openly associates to earthquakes (Chapter CLXVIII) (Fig. 13):

«The church began to tremble; and the air rumbled, and it seemed to him that the wind was blowing so strong that the earth quivered, as he had already heard and seen out of the winds, which erupt from the ground and are called earthquakes. But these were no earthquakes at all, they were fiendish demons...»

[In the original Italian text: «La giesia comenzò a tremare; e l'aere tonava, e parevali che si grande el vento traesse che la terra tremasse, come certe volte lui havea zia per venti sentito e veduto, che esseno de la terra, che sono chiamati terremoti. Ma questi non erano terremoti, anzi furono demonii infernali...»].

And Antoine de la Sale, in his The Paradise of Queen Sibyl, lets his characters make an experience of the poweful subterranean winds which circulate beneath the earth, within the bowels of the Sibyl's Cave (Fig. 14):

«So they went through that narrower hollow, going ahead for some three miles, as they reckoned. Then they found a crevice which split the cave: a wind issued forth from the crevice, so horrible and astounding that no one of them dared to go ahead of a single step, or even half of it; because, when they tried to get nearer, they felt that the wind was trying to carry them away».

[In the original French text: «Allerent par ceste plus basse cave, tousdiz en avalant, bien l'espace de trois milles a leur advis. Lors trouverent une vaine de terre traversant la cave, dont yssoit un vent si treshideux et merveilleux que ne fut celui qui osast aler pas ne demy plus avant; car, aussi tost qu'ilz approuchoient, leur sembloit que le vent les emportast»].

Winds and earthquakes. Winds which blow through the unseen hollows of the earth. An antique credence which is fully known to authors like Andrea da Barberino and Antoine de la Sale, who include mentions of it in their respective works.

From the Renaissance onwards, a renewed interest on the puzzling issue of the origin of earthquakes will bring scholars and philosophers to the production of additional conjectures, as for instance the theory proposed by Immanuel Kant on the combination of hot gases of sulphur and iron in subterranean caverns and pits.

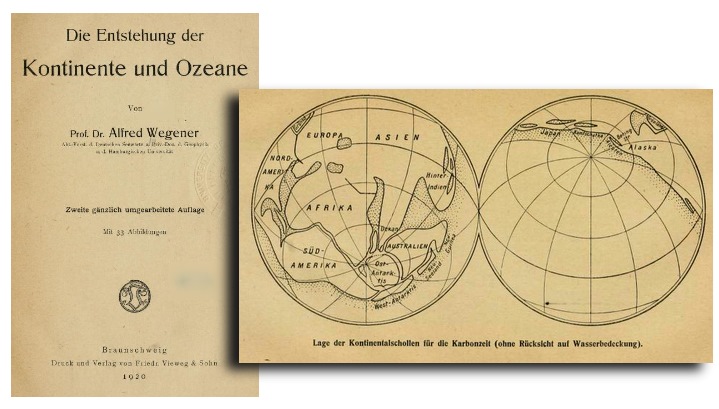

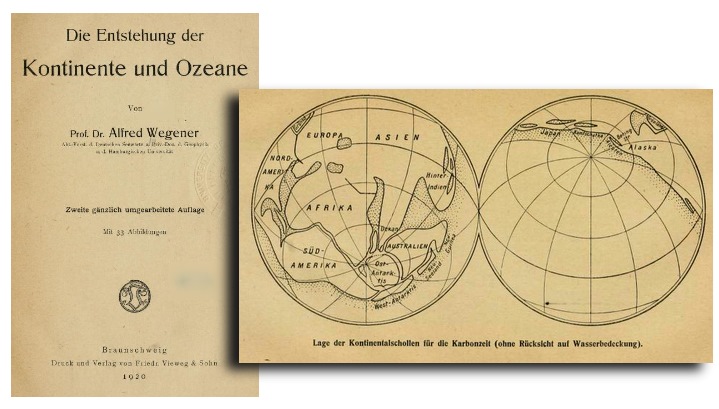

It will eventually be in the nineteenth century that the physics of waves travelling through the earth will be discovered and studied. A century later German scientist Alfred Wegener will set down his theory on continental drift and plate tectonics, the fundamental key to a scientific understanding of earthquake's nature and characteristics.

So, for more than seventeenth centuries, from Aristotle, Titus Lucretius Carus, Lucius Annaeus Seneca, Pliny the Elder and up to the late Middle Ages, earthquakes and winds and tempests will be part of a same, homogeneous vision of the mighty powers which conveyed destruction on earth.

And this identity of vision is fully retrievable in the literary tradition which concerns the legendary tales of the Sibillini Mountain Range, in the Italian Apennines.

A further indication that our conjecture, based on earthquakes and their terrifying effects, is bringing us on a promising course.

Monti Sibillini, la leggenda ctonia /6.6 I terremoti come effetto dei venti sotterranei

Nella tradizione leggendaria dei Monti Sibillini, i venti e le tempeste non sono, semplicemente, normali venti e tempeste.

Come abbiamo avuto modo di affermare nel paragrafo precedente, c'è molto di più.

Un primo indizio che viene a segnalarci lo speciale carattere dei venti in questo contesto magico ci viene fornito da quello stesso Pierre Crespet dal quale abbiamo tratto alcuni brani in relazione alla Grotta della Sibilla, tratti dalla sua opera "De la hayne de Satan et malins esprist contro l'homme", pubblicata nel 1590.

Come abbiamo già avuto modo di notare nel nostro precedente articolo, "Monti Sibillini: la leggenda prima delle leggende", Crespeto fornisce un riferimento aggiuntivo concernente la magica, divina qualità di tali venti e tempeste (Livre I, Discours 6) (Fig. 1):

«Gli Dèi celesti o forse le stesse stelle inviano questi venti

Spesso accade infatti che un negromante, in cerca di un tesoro nascosto sottoterra,

o desideroso di consacrare un proprio libro,

oppure tentando con un magico rituale di soggiogare una divinità,

ho udito che i venti allora si levino, e improvvise tempeste si scatenino».

[Nel testo originale latino:

«Hos ventos vel Dij aerij vel sydera mittunt,

Sepae etenim cum thesauros tellure latentes,

Vult auferre Magus vel consecrare libellum,

Vel magico ritu quemquam sibi subdere divum,

Audivi exortum ventum, subitamque procellam»].

Questa suggestione, che Crespeto trae a propria volta da un'opera cinquecentesca, "Zodiacus Vitae", scritta da Marcello Palingenio Stellato nel 1536, conferma la possibile interpretazione delle tempeste e della devastazione che ne consegue come qualcosa di diverso da una mera turbolenza atmosferica, per quanto intensa essa possa essere.

E questi venti non sono solo connessi all'arte della negromanzia, perché Palingenius, nel proprio poema, aggiunge le seguenti parole (Liber XI, "Aquarius") (Fig. 2):

«Sappi dunque che innumerevoli, immense caverne

giacciono sotto la terra, e lì quando venti potenti

sono generati, essi suscitano selvagge

battaglie, percuotono la terra, e con straordinario furore

si radunano e abbattono città intere con le loro mura.

Poi in qualche luogo essi erompono come esercito, e nell'aria

si diffondono, svanendo infine e placandosi. [...]

Così si agitano i venti, che i regni sotterranei

abitati dalle ombre dei morti, abitano nell'oscurità delle grotte».

[Nel testo originale latino:

«Scire igitur licet, innumeras vastasque cavernas

Sub terris esse, atque illic quandoque creari

Ingentes ventos; qui dum crudelia miscent

Proelia, concutiunt terram, nimioque furore

Congressi evertunt totas cum moenibus urbes.

Donec parte aliqua erumpant facto agmine, et auras

diffusi in vacuas non longa pace quiescant. [...]

Hos agitant ventos, qui subterranea regna

Dij manes habitant, caecisque morantur in antris.»].

Perché i venti sono miticamente legati ai terremoti.

La connessione tra tempeste e onde sismiche non rappresenta affatto un concetto sviluppato nel sedicesimo secolo da Palingenio. In effetti, esso costituisce la più antica spiegazione prescientifica in relazione all'origine dei terremoti.